Living With an Invisible Disability in Donald Trump’s America

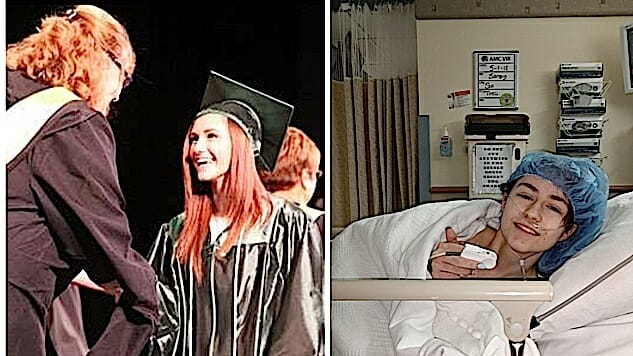

Photos courtesy of Tayler Stukey Politics Features Healthcare

Until she collapsed climbing the stairs on her way to class this past September, Tayler Stukey thought she was an average, healthy 19-year-old college sophomore with an eye to the future. Veterinary school was the plan, and nothing would stop her. Sure, she’d dealt with unexplained exhaustion and body pains her whole life, but didn’t everyone? That’s what her mother had always said, though Stukey was skeptical. The previous week she had gone “foggy” during a math test, finding herself unable to read or comprehend the words on the page. It had been a thoroughly unpleasant, jarring experience, and ever since, walking around campus—particularly on staircases—had been a struggle. Still, she’d done her best to put it behind her.

But this time was different. Unlike previous incidents, there was no gritting her teeth and bearing it. Stukey’s legs had simply given out from underneath her and to her horror, she could not pick herself back up. Luckily, a friend passing by noticed her distress and carried her back to her dorm room. Shortly thereafter, a physically diminished Stukey took a necessary medical leave from school. Several doctor visits and nearly three months later, her rheumatologist diagnosed her with hypermobility Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), the least severe form of a somewhat rare (1 in every 200-500 people are affected), but highly debilitating genetic connective tissue disorder that works by changing how collagen is deposited in the body and disrupting connective fibers in joints and muscles. It is known to cause soft, smooth, sometimes elastic skin, easy bruising, chronic muscle and bone pain, and hypermobile joints.

Fortunately, thanks to her stepfather’s work, Stukey had insurance through MVP Health Care, which she thought would allow her to get back on her feet in a reasonable amount of time. However, she would soon discover that having insurance in 2018 hardly meant a guarantee of adequate care.

Part of the problem was geography. Living in a small, rural upstate New York town, Stukey tells me she had difficulty finding doctors who knew anything about her condition. At one appointment, she even had to spell “Ehlers-Danlos” for the physician. “They have no idea what it [EDS] is,” she explains, exasperated, noting that the specialists she needs are often hours away—which is more than an inconvenience considering Stukey cannot drive due to her condition, and is wholly reliant on family members, all of whom work.

Upon leaving college, she had to move in with her grandmother because she could no longer climb the stairs at her father’s house, and he worked during the day anyway. Stukey often requires assistance to do basic tasks. She struggles to dress herself in the morning and cannot easily stand for more than 3 minutes at a time during a flare up. Sudden weight shifts while sitting, she explains, could push her hip out of place thanks to her “stretchy” connective tissue.

“I’ve lost my independence and freedom as a young adult entirely,” Stukey laments. “I can’t choose to push myself like I used to be able to because I know how much it’ll hurt to recover and how incapacitated I’ll be.”

The picture below illustrates the the extent of the care Stukey requires:

Compounding the transportation issue is the not insignificant matter of a $500 deductible. To Stukey, who is physically unable to work and whose primary source of financial support is her grandmother, the costs of care are prohibitive. Although her insurance “is really good about what they cover,” she tells me, “the copays are crazy.”

“It’s $50 to go see a doctor; it’s no help—we can’t keep doing that,” she says. ”And we don’t have leads on where to go because it’s hit or miss on if the doctors are going to understand what I’m dealing with or if they’re going to say I’m too complex and they can’t handle it.”

Her voice shakes slightly as she continues on, adding that in order to recover, she should be in pain management, but cannot afford the $150 it would cost just to have someone “rotate [her] pinky a little.”

In a Twitter direct message, Stukey outlined what her costs would be were she to have the care she needs:

Joint physical therapy would cost 100-150 per week. Additional massage therapy for pain relief would cost another 100 a week. Going back to manual therapy for my cystitis is another 100 a week. My current medications are $50 a month and that’s just GI and one POTS pill. Plus if I get injections for pain relief that’s 150 per procedure every other week or once a month depending. This is all before I even count copays for doctors, copay costs to get custom bracing and orthotics and mobility aids, and before any other treatments I may not know of. My parents can’t financially help, so my grandma does it all. And she isn’t hurting for money exactly, but she just can’t do all that on her own, plus gas, driving an hour there and an hour back for every appointment (or sending me on $120 Uber rides, which we refuse to do).

The end result of these barriers to care is that Stukey does not receive it consistently, making independence seem a distant fantasy. She does not qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), not having held a job long enough to earn the necessary work credits (the requirement increases as one ages), and she lacks the support needed for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). As Stukey explains, her family has not applied because “the process is just as painstaking to get through, I’d need to hire a lawyer, and it’s usually years of appeals and hearings and repeated denials.”

As such, Stukey, like thousands of other Americans, has reluctantly turned to crowdfunding—albeit through a GoFundMe page left up on her Twitter which she does not promote. “I’m not comfortable asking for money,” she explains.

The US faces a humanitarian crisis when it comes to the state of its health care system. In 2014, the CDC put out a shocking press release. “Up to 40 percent of annual deaths from each of five leading US causes are preventable,” the headline read.

Even with the Affordable Care Act in place, costs have become prohibitive. With most Americans living paycheck-to-paycheck, in debt and unable to afford a $1,000 emergency, it is unsurprising that over 600,000 go bankrupt every year due to medical expenses—though the exact number is difficult to nail down. In 2016, the average annual medical cost per person was $10,345. That’s more than a third of the average annual income for an individual ($34,940). Last year, Quartz reported that nearly half of the money raised through GoFundMe went to medical expenses.

The federal government’s response to this ongoing crisis has been uneven at best. The Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare) was able to put a stopper on some of the more inhumane practices of the insurance industry, like denial for “pre-existing conditions.” But it left in place the basic framework of a broken model, largely thanks to the efforts Obama aide Jim Messina, who made sure grassroots groups in favor of single-payer or a public option were kept out of the negotiations. While the ACA did bring the number of uninsured down to historic lows, a staggering 41 million are underinsured with costs rising faster than wages, according to findings from the Commonwealth Fund in 2017. Meanwhile, 28 million lack insurance altogether.

During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised fixes, hinting at a government-funded replacement for the ACA. But since his election, he has apparently given up on the pursuit, and such a plan has not manifested. Instead, the president offered the country a bill which would have rolled back much of the ACA without any replacement but placated the insurance companies. The American Health Care Act of 2017, as it was called, failed to garner the support needed in Congress largely due to grassroots efforts to flood legislative offices with phone calls and emails. The president shrugged off the defeat, spitefully calling it politically advantageous because the current health care law would “explode.”

“I’ve been saying for the last year and a half that the best thing we can do politically speaking is let Obamacare explode,” he said.

It was an incredible statement from the man elected to be the nation’s top executive—an acknowledgment that he intended to do nothing while the people languished and died, simply as a way of sticking it to defiant Democrats and his detractors. To this day, the health care crisis remains unaddressed at the federal level since President Barack Obama left office, save for the unhelpful, slow chipping away at his signature legislation, like the repeal of the individual mandate.

This week, news broke that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services were cutting funding to an ACA enrollment assistance program. This move comes as the latest attack on the legislation by the Trump administration which last month, issued a new rule allowing small businesses to circumvent ACA regulations to set up health care plans with fewer benefits. Before that the Justice Department announced that it would not defend the ACA in court, claiming that certain provisions, including the protections for individuals with pre-existing conditions, were unconstitutional.

But governmental inaction hasn’t deflated Stukey, who despite everything has maintained a positive outlook. “I have an amazing boyfriend,” she tells me, explaining, “he’s done more research than I have!” Recently, she received the good news that her deductible had been fully paid, and that she may soon get a wheelchair—assuming she can afford the 30 percent of the cost her insurance company is requiring her to pay, even with an in network vendor. Still, Stukey says she is more motivated than ever to regain her independence and advocate for those in her position.

“Legislation needs to recognize and adequately address this crisis that the chronically ill are suffering through,” she writes in a direct message, citing the need to improve accessibility and medication distribution. “It is also CRUCIAL that Trump is not allowed to change or even remove protections on pre-existing conditions in healthcare. I mean seriously, how can anyone look at someone born sick and tell them they don’t deserve insurance?”

Anyone interested in donating to the Ehlers-Danlos Society can do so here.