This post is part of Paste’s Century of Terror project, a countdown of the 100 best horror films of the last 100 years, culminating on Halloween. You can see the full list in the master document, which will collect each year’s individual film entry as it is posted.

The Year

Overall, this is a solid frame that is marked by the stomach-churning presence of several of the mid-2000s “extreme horror” films that generated the most negative discussion during this era. The likes of Saw 2 pushed that series far beyond the more modest setup of the original film, while Wolf Creek made headlines in Australia and Eli Roth’s Hostel stirred up considerable anger in the U.S. There is a sense here of horror establishing some new boundaries as far as cinematic brutality is concerned, pushing well past the likes of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre to depict scenes of realistic torture and dismemberment that are delivered with an air of harrowing seriousness rather than slasher-esque glee. Those critical of the new wave derided all such films under the blanket term of “torture porn,” while defenders turned toward almost Freudian psychoanalysis to probe the trend for deeper and more primal meaning. 15 years later, it’s still not entirely clear who was in the right.

Outside of the films directly accused of bearing the torture porn label, the trend toward the extreme and risque is present in several of the other most notable offerings. The Devil’s Rejects certainly pulls no punches in its wanton bloodletting on the part of the villainous Firefly family (recently returned to the screen in the poorly received 3 From Hell), and is usually regarded as director Rob Zombie’s strongest overall offering to date. Hard Candy, meanwhile, also raised a lot of eyebrows in 2005 for a storyline that was difficult for many people to accept on basic premise: A 14-year-old girl lures in an older man with sexual innuendo before subduing him and torturing him for reasons of her own. The film is still worth seeing in 2019, however, for the strong central performances from Patrick Wilson and a debuting Ellen Page.

The rest of 2005 features films that both conform to trends of the day, such as the J-horror fervor still going strong in Noroi, and entries that stand out as much more individualistic, like the black-and-white, silent film parody of H.P. Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu, which faithfully adapts one of the author’s best-known stories. Feast also falls delightfully into the latter camp; a very fun examination of monster movie and “hero” tropes that establishes a familiar horror film situation and then purposely veers in unexpected directions.

Finally, 2005 is also home to George A. Romero’s Land of the Dead, considered by many zombie geeks—myself included—as the last essential entry in the original “of the dead” series, taking some of the themes of Day of the Dead to their logical conclusion, even if the overall story isn’t exactly what it could have been. Still, these are the last fumes of Romero as a significant creative presence, before Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead returned to retread what had become very familiar ground.

2005 Honorable Mentions: The Devil’s Rejects, The Exorcism of Emily Rose, Hard Candy, Feast, Noroi: The Curse, Land of the Dead, The Call of Cthulhu, Saw 2, Wolf Creek, Corpse Bride

The Film: The Descent

Director: Neil Marshall

Stories that genuinely revolve around female relationships are incredibly rare in the world of horror. It is, suffice to say, one of the genres that tends to have the fewest films passing the Bechdel test, even though the central protagonists of certain genres (such as slasher movies) are often women. All too often, though, these women are simply defined by their relationships with male protagonists, or as the target of a male antagonist, such as your classic, masked slasher villain (Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers, etc). The Descent would already stand out in this genre just for the fact that its protagonists are exclusively women, but the lack of a clearly “male” villain pushes it farther from the center, into territory that is still very rarely explored. As a result, it possesses a timbre all its own—a true female voice, even though it was written by director Neil Marshall.

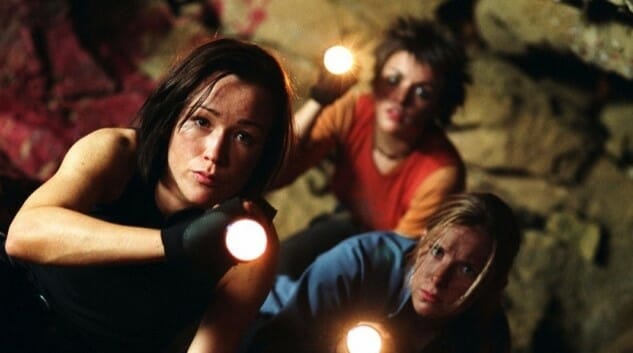

The Descent is about widowed former mother Sarah, who reunites with a group of friends a year after losing both her husband and her young daughter in a car wreck. Together, as a way of healing their group dynamic (although the film doesn’t say it so bluntly) and bringing Sarah out of her depression, the group plans to go spelunking, exploring an unmapped section of caves deep in Appalachia. After a cave-in, however, the group is left with only one choice—move further into the ever-blacker abyss, as the walls close in, the air grows stale, and strange sounds begin to creep up from the depths …

Yes, this is ultimately a creature feature, but describing The Descent as a “monster movie” unfairly minimizes its uncommon gravitas and expertly executed slow-burn. Indeed, the most impressive aspect of this film is likely its incredible patience and ability to flesh out its characters while imperceptibly turning up the tension, scene by scene. As the group descends into the heart of the cave system, they’re routinely squeezing through narrow cracks that represent what is arguably the ultimate harnessing of claustrophobia as a cinematic scare tactic. These scenes seem to go on forever, to the point that the audience is already on the edge of its seat by the time one of the creatures finally makes an extremely memorable first appearance. It’s a proper, switch-flipping moment: What had been a quiet, claustrophobic film soon erupts in a geyser of blood, as the spelunkers are not only torn asunder, but have their relationships torn apart as well. It’s all impeccably written, with several members of the group being fleshed out nearly as well as de facto protagonist Sarah, making you care about each of them as individuals. The audience, in fact, is given the perfect degree of information—we understand more about what has happened than any of the single characters do, allowing us to perceive an extra layer of tragedy in how misunderstandings and old grievances undermine the fight to survive.

Of course, that isn’t to say The Descent isn’t effective as a limb-snapping creature feature at the same time. Its monsters, loosely theorized to be some kind of cave-deformed, troglodytic, cannibalistic human offshoot that hasn’t seen the light of day in generations, are truly a sight to behold, in limited moments when you can behold them. They hunt in packs, looking vaguely like more feral versions of Gollum, weak in terms of eyesight but with greatly enhanced senses of hearing and smell. The central nest makes their efficacy clear, as human bones are mounded in a vast sepulchre of forgotten violence, dating back what must be decades. Seeing it, there is a sense that all our characters are far beyond any kind of help or hope.

Ultimately, The Descent is simultaneously as well-characterized and merciless as modern horror films come. With an ending that nicely pays off several of its running threads (although you should make sure you’re watching the original UK ending, instead of the U.S. cut), it prioritizes pure horror above all else. It is absolutely among the most effective horror films of the 2000s.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident horror guru. You can follow him on Twitter for more film and TV writing.