Nintensive Care: How 1979’s Sheriff Foreshadowed Nintendo’s Success

Subscriber Exclusive

Games Features nintendo

Nintensive Care is a new, subscriber-only column that tracks the history of Nintendo’s videogame era and its outsized influence on games and the gaming industry. For our first column we look at 1979’s Sheriff, the first Nintendo arcade game to feel like a unique, intentionally designed piece of work, as well as the first notable assignment for the company by a young artist named Shigeru Miyamoto.

Let’s do this quick. In 1889 a company called Nintendo was founded to produce hanafuda cards from its headquarters in Kyoto. 76 years later it started selling toys. One of those, released in 1970, was a light gun called the Nintendo Beam Gun. Two years later the company teamed up with Magnavox to create a light gun for its Odyssey home videogame console; a year after that Nintendo opened a series of light gun shooting gallery arcades in Japan. In 1975 it released its first non-light gun arcade game; EVR Race, designed by Genyo Takeda, consisted of a large table where up to six players could “gamble” on prerecorded horse and car races that played on an attached TV. By 1977 Nintendo was releasing its own gaming consoles exclusively in Japan, and the next year it stepped into the traditional arcade game market with a cocktail cabinet version of the board game Othello. After the smash success of Taito’s Space Invaders in 1978, Nintendo released a clone called Space Fever in 1979, and then, eight months later, in October 1979, another Invaders-inspired game called Sheriff.

Okay: we’re caught up.

As you can tell, Sheriff is far from Nintendo’s first arcade game. It’s the right one to start with when you’re discussing what really makes Nintendo Nintendo, though. Not only is it the company’s first videogame with its own identity, and the best of its pre-‘80s games; it displays the growth of designer Genyo Takeda, who would go on to create the Punch-Out series and StarTropics, and also marks the debut of a pretty important person in Nintendo’s history: Shigeru Miyamoto, who was responsible for the game’s pixel art. In many ways Sheriff is where the Nintendo we know in America really begins.

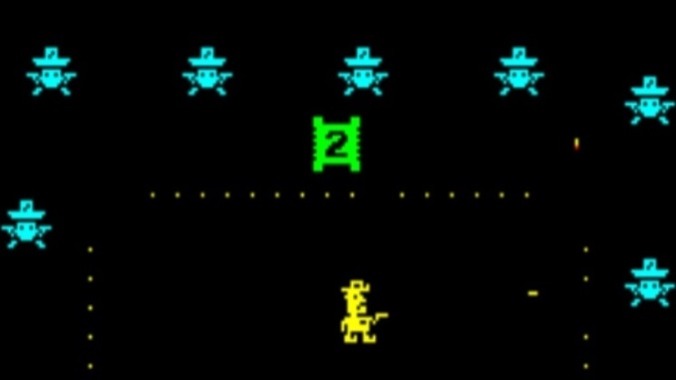

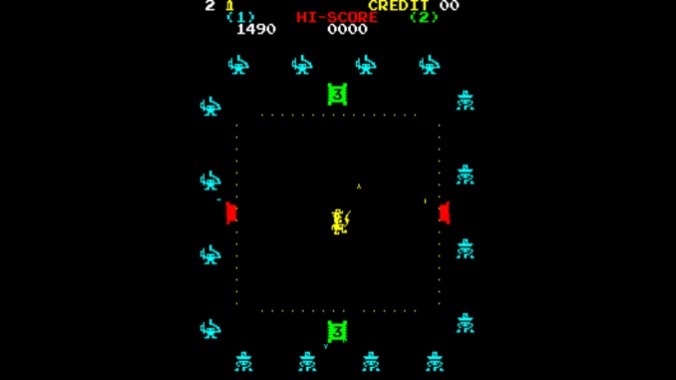

In Space Invaders you control a cannon at the bottom of the screen trying to stave off columns of aliens marching down towards you. In Sheriff you control a gunslinging lawman in the middle of the screen trying to stave off a gang of bandits encircling you. Takeda took the essence of Space Invaders—shoot the things trying to shoot you—and gave it a new perspective. Sheriff also changes things up by letting you move your character in multiple directions, and not just on a horizontal axis, and by having bandits occasionally rush you. The original arcade cabinet also has a unique approach to shooting; your cowboy can fire in eight directions, and you use a dial to aim. It borrows a couple of other ideas from Invaders—there are barriers that can block shots but crumble more and more with every hit, and occasionally a bird will fly by at the top of the screen, giving you bonus points if you shoot it. (I guess it’s a lawbreaking bird?)

The Space Invaders influence is immediately obvious, but during an era when most videogames were content to just rip Taito off (see Nintendo’s own Space Fever), Sheriff at least experiments with the formula in a way Nintendo would come to be known for. Takeda’s inventive approach effectively turns Sheriff into a genre of its own; its multidirectional shooting makes it a precursor to games like Robotron: 2084, while its western theme sets it apart from the sci-fi games that proliferated during the nascent arcade era. That was probably enough to make its clear similarities to Space Invaders less than obvious to many of the children who would’ve played it back in 1979.

It’s also one of the very first videogames to try to tell a story outside of its in-game action. Sheriff’s cutscenes hit arcades just one month after the game that introduced the concept (a Space Invaders sequel, of course), and they tell a stereotypical damsel-in-distress story. The sheriff—who actually has a name, Mr. Jack (why not Sheriff Jack?)—is trying to rescue Betty from a gang of bandits. Obviously the only resort is to kill them all. A cutscene runs between every level, showing either Jack rescuing Betty or the bandits chasing her down, and although it might seem minor today, this (along with other games that pioneered the cutscene in 1979 and 1980) was one of the first steps towards the cinematic style of storytelling found so often in games today.

That also points to one of Sheriff’s other notable traits, the one that most establishes it as a cornerstone of Nintendo’s legacy: this game’s characters have character. Mr. Jack might look like a stock cowboy at first, but Miyamoto’s pixel art is deceptively detailed. His square jaw and crumpled nose can be read as either the hallmarks of a hardboiled detective, making Mr. Jack a kind of Old West Dick Tracy (Jack’s bright yellow sprite reinforces that impression), or as the weary exhaustion of somebody tasked with maintaining law and order in a fundamentally lawless place. Meanwhile the bandits look like blue skulls in broad brimmed hats; they march back and forth looking like death itself, firing two pistols and occasionally whipping their hats off, before occasionally charging towards Mr. Jack. Miyamoto didn’t have much to work with, given 1979’s technology, but his art breathes personality into Sheriff, at a time when that was hard to find in games.

Personality, of course, is one of Nintendo’s primary hallmarks. It’s a big reason Donkey Kong became such a smash a couple of years later, and why characters like Mario, Link, Samus, and Kirby continue to enchant players decades after their debuts. Sheriff isn’t quite there yet—it might have far more personality than other ‘70s games like Invaders, Asteroids, and Head On, but it’s still rudimentary, and would be shown up just months later by Pac-Man—but you can see the seeds of what Nintendo would become, far more than you can in Space Fever.

Another thing Nintendo is known for that isn’t present in Sheriff, sadly, is fine-tuned controls. Mr. Jack is slow to respond when you make him move, and he automatically points his pistol down after every shot, so you can’t line up multiple shots in a row. Combined it can be pretty frustrating. It takes several plays to get that response speed down and get used to constant aiming, and for me, at least, it never quite became second nature. It can be especially annoying when the bandits rush towards you. It’s also just too repetitive in the way many early games are; the level design never changes, with the same 16 bandits moving roughly in the same way on every screen.

Still, Sheriff hints strongly at what Nintendo would quickly become. It’s a Nintendo confined by the limited tech of 1979, but one that’s clearly trying to break out of those restraints through innovative action and character design. Takeda went on to make some of Nintendo’s best and most beloved games, but it would take Miyamoto’s step into game design for Nintendo to get its first major hit two years later, building on what he started with Sheriff, and, eventually, truly establishing the company that has gone on to define videogames for so many.

Senior editor Garrett Martin writes about videogames, comedy, travel, theme parks, wrestling, and anything else that gets in his way. He’s also on Twitter @grmartin.