Welcome to Film School! This is a column focused on movie history and all the stars, filmmakers, events, laws and, yes, movies that helped write it. Film School is a place to learn—no homework required.

Sex and violence are both the bugbears of modern movies and the foundation upon which they were founded. Despite the tedious omnipresence of censors, people have wanted to see kissing and punching recorded since the technology was possible. If you could see shirtless men smacking each other around, well, for many that became a one-stop shop. As Christina Newland noted in her list of the best boxing movies of all time, some of the very first movies were boxing matches, helping blur the line between in-person entertainment and the burgeoning cinema. These were little films, a few minutes max, that emphasized this new art form’s capacity for movement. But the ring was also where movies would make the leap from peep show gimmick to a full evening’s entertainment, with the first feature-length film: The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight.

That’s right, the first feature-length movie was a documentary. Not only that, it was a documentary filming something that was, at the time, illegal in 21 states. The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight—capturing the 1897 bout between James J. Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons over the course of 100 minutes—was the result of two forces that would come to dominate the movie industry: Technological innovation and greed.

Companies want to make money, and the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company was no different. Founded by Confederate scum Woodville Latham, the production outfit employed technicians like William K. L. Dickson, Eugene Lauste and Enoch J. Rector to shoot boxing matches (like Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph) one minute at a time. These were displayed, round by round, in peephole Kinetoscopes. Not super satisfying, not super profitable. More like gumball machines than a box office. Rector soon branched out on his own, both he and the peers he left at Latham’s company trying to shoot something a little longer and a little more gratifying.

Lauste was most successful, making longer movies possible through a groundbreaking invention: The Latham loop. This tension-alleviating innovation (a small mechanical detour that absorbed strain on the film strip) allowed much longer amounts of physical film to be used without tearing, both when shooting and projecting. With that problem solved, runtimes were limited only by the amount of film you had. This loop would become standard in both film cameras and projectors.

But it wouldn’t be the fix used by Rector, who went in a different direction. His plan discarded engineering elegance for brute force: Instead of fixing the tension problem with a clever bit of tinkering, he just made a camera big enough for a team to fit inside, with the people themselves in charge of keeping the film strip intact. The Veriscope was basically a big shed-camera filled with a three-man team running around its mechanical guts. They were responsible for cranking, feeding and tending to slack in the line. But hey, a sloppy solution is still a solution. So why not shoot a full version of what Kinetoscope had been specializing in?

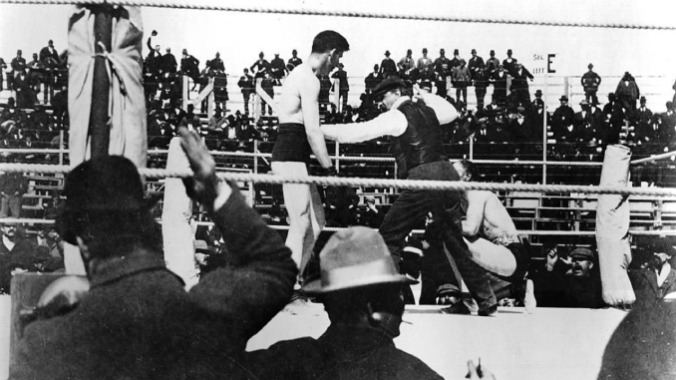

Rector contacted boxing promoters to wrangle Corbett and Fitzsimmons into a fully filmed championship bout. The date was set, the profit share negotiated, the ring cut down to fit within the frame (and then reverted to standard size once the referee caught wind). The resulting heavyweight prizefight was almost as massive as Rector’s ridiculous Veriscope. These were big names, and bloodsport was at a popular peak. Wyatt Earp (yes, that Wyatt Earp) covered the fight for The New York World: “I consider that I have witnessed today the greatest fight with gloves that was ever held in this or any other country.” Presumably Wyatt Earp was humbly reminding us that he had seen greater fights that used other weapons. But the filming went off without a hitch, and it was the longest movie ever made.

Fourteen rounds, a knock-out blow to the solar plexus, a controversial jab to the jaw—The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight had plenty to offer even the boxing novice. Those more in the know were up in arms about a possible foul, anxious to check the tape in one of the first instances of sports fans feeling smug that the recording would disprove the ref.

And fans poured into the theaters as The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight toured around the country. Oh, right. That illegality thing? Well, here’s the deal: Prizefighting was illegal. Prizefighting movies weren’t. As long as the fight had already been held (and filmed), showing it around wasn’t breaking any laws. That loophole opened up a massive revenue stream for boxers, who had mostly been making ends meet by doing public appearances and stage performances. Suddenly, fighting made money.

Not only that, but it allowed women to get all flustered by seeing two half-naked men go to town on each other—a rarity at the time, because the actual in-person boxing matches weren’t exactly welcoming to anyone but more disreputable men. Movies became a cultural equalizer, smoothing out social mores and allowing a (relatively) diverse crowd to experience a taboo together. It became more socially acceptable, because there was a level of artistic distance—even if it was a documentary. (In a strange twist, the first feature film also got the first mockbuster treatment: Two railroad workers were dressed up like the star boxers and filmed in the Reproduction of the Corbett and Fitzsimmons Fight. When confronted with complaints an exhibitor replied “What do you expect for 10 cents, anyhow?”)

Sure The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight was grainy and inconsistent, and the “flickering and vibration were most troublesome to the view and extremely trying to the eyes,” according to the New York Tribune coverage. Surviving footage is jittery and jerky, but crisp enough to see spectators nudge each other in a timeless, universal gesture of “Buddy, can you believe this?” Rector’s fixed-angle cinematography was nothing special, and it’s easy to imagine the eyestrain the imperfect materials would inflict. But, for the first time, audiences got to sit in a theater for an hour-and-a-half and watch a full boxing match that they did not attend. An expert provided narration alongside the footage—a sports commentator. Modernity was right around the corner.

As Charles Musser notes in his excellent book The Emergence of Cinema, this was not just the advent of modern-length feature films, but a new kind of engagement with events. “Before cinema, an event could not really be re-presented. It could be recounted, recreated, or repreformed,” he writes, but these always had a high level of subjectivity. There are still countless choices made when filming even the simplest and most hands-off documentary, but with The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight, people didn’t have to read a sports column or hear about it secondhand. They could just sit down, watch and decide what they thought for themselves. The movies gave them a little slice of power, and shared a little more of the world with them.

This is what boxing gave to the movies, and it’s never lost its cinematic appeal. That was true when Martin Scorsese was changing the game with Raging Bull in 1980, and it was true when Thomas Edison took a break from inventing every single thing in order to record The Gordon Sisters beat the ever-loving hell out of each other in 1901. Whether we were cheering to Rocky’s theme or pulling for The Hurricane, boxing remains an elegant, kinetic, immediately understandable subject that could lure each and every one of us into the cinema, pulled by our basest instincts. A century after The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight, in 1997, the industry had changed, but less than you’d think. Boxing was on pay-per-view premium channels like HBO. Ving Rhames would play Don King in an HBO TV movie that year. It was only 12 minutes longer than The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight, the movie that had changed everything 100 years prior.

Jacob Oller is Movies Editor at Paste Magazine. You can follow him on Twitter at @jacoboller.

For all the latest movie news, reviews, lists and features, follow @PasteMovies.