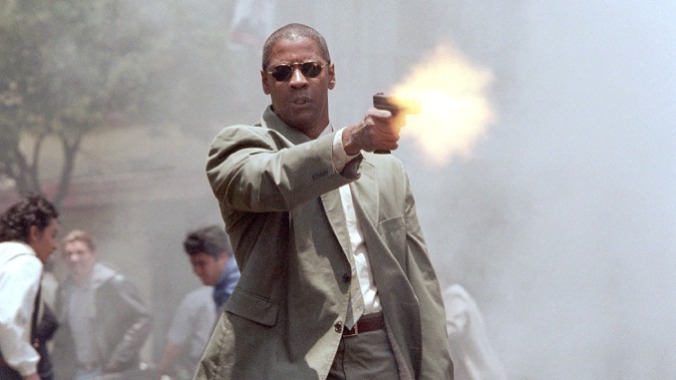

Man on Fire Turned Mexico City Into a War Zone 20 Years Ago

Tony Scott’s impressionistic revenge tale remains a mini-genre of one.

Movies Features Denzel Washington

Action movies would have you believe that the wider world exists for white ladies to get kidnapped in, and for men recovering from their shady, painful pasts to wreck house and rack up the bodies while they go rescue said white ladies. (They would also have you believe that foreign countries are all either ludicrously desaturated or else kind of orange.) If there’s any Spanish going on, lord help you: American audiences know just enough of it that you’ll get some characters who talk in Hollywood Spanglish while also having well-paid Latin American actors say lines like “He belongs to a brotherhood called ‘La Hermandad.’” (“Hermandad” is “brotherhood!” Come on!!) Man on Fire, Tony Scott’s 2004 contribution to a year in cinema that belonged almost entirely to the revenge picture, does not challenge any of this Gung Ho American Savior nonsense at all.

But being as Man on Fire also features Denzel Washington at his stone-cold killing best, skeezy supporting characters that include Giancarlo Giannini, Mickey Rourke and Christopher Walken, and the white girl in question is Dakota Fanning doing a way better job the situation calls for, I give it a pass. Scott went for a feverish, impressionistic haze of a revenge flick that seems like it was meant to kick off an entirely new subgenre. Instead we just got this movie and the videogame Max Payne 3. I’ll take it.

It’s true enough that abductions remain common in parts of Mexico. Man on Fire paints a picture of a callous, dangerous city where a kidnapping-industrial complex run by a kingpin called “La Voz” organizes the capture and ransom of poorly protected rich people. Corruption and thievery is so rampant that most police are simply in the pocket of the kidnappers.

Creasy (Washington) is a semi-retired badass with a drinking problem. Rayburn (Walken) is his friend and former handler, living it up in Mexico. He recommends Creasy for a gig as a bodyguard—it won’t be much of an assignment, so if he’s half-cut it won’t really matter. Brian Helgeland’s script is pretty mercenary about the whole operation: Creasy openly admits to being a functioning alcoholic who can only provide as much protection as he’s paid. His employer, family patriarch Samuel (Marc Anthony) is pretty blasé about it all, operating on cynical advice from the family lawyer (Rourke) to keep the overhead on his daughter’s security low. But Samuel’s wife Lisa (Radha Mitchell) sees something in Creasy that convinces her to hire him on the spot.

The important relationship here, though, is with Creasy’s young principal: Lupita (Fanning), who steals the first reel of the film. Fanning, who is still teeny-tiny in this movie, melts Creasy’s frozen heart, unknowingly pulling him back from the brink of suicide. So of course she will need to get kidnapped.

Fanning holds her own in the above scene, which dials up Paul Cameron’s tweaked-out cinematography to a fever pitch. Much of Man on Fire is shot muddily, with odd double exposures, wavering camera movement, erratic framing, or with effects like the reflection of a window between the camera and its subject. Subtitles, when they appear, are designed to be maximally intrusive, timed to character’s precise syllables and in all sorts of different typefaces. The effect is almost impressionistic, reflecting Creasy’s paranoia, his drunkenness, his seething rage.

Grievously wounded in the kidnapping, Creasy awakens to discover that Lupita has been killed after a screw-up during the ransom. Filled with grief and rage, he vows to kill anybody and everybody responsible and goes about doing just that. Helping him on the sly are crusading reporter Mariana (Rachel Ticotin) and good cop Manzano (Giannini). As Rayburn tells Manzano in the monologue for which Walken was unquestionably cast specifically to deliver, someone can be an artist in any medium. Creasy’s art, Rayburn says, is death, and he’s about to paint his masterpiece.

From there, Man on Fire becomes an episodic tale of violence and torture, as Creasy tears La Hermandad apart. Washington has been a bad dude of cinema since pretty much the moment he quit starring in St. Elsewhere, and there’s a reason he is still making movies like Equalizer 3. He can make Macbeth sound as if it was written specifically for him. He can embody the physicality of a guy you believe was trained by Rambo. He can convincingly pal around with a tween girl in the same movie where he cuts off a dude’s fingers and cauterizes them with a car’s cigarette lighter.

Man on Fire is actually a remake of a 1987 movie with Scott Glenn in the role of Creasy, itself based on A. J. Quinnell’s 1980 book. The story was originally set in Italy and featured the young girl being kidnapped by the mafia, and the movies both follow the novel’s plot in their broad strokes. Creasy discovers that the kidnapping was orchestrated by Lupita’s father so that he could make off with a bunch of money, so the movie features Marc Anthony actually committing seppuku out of shame.

Eventually Creasy does make it to the end of his roaring rampage of revenge, Man on Fire pulling its last punch to deliver a happy ending. It’s a sudden ending, almost an afterthought when what we expect is some final no-holds-barred action setpiece. It still looks and feels like no other movie that came out that year—and very, very little that has come out since has in any way emulated it. John Wick owes some aesthetic touches to it, mostly in its ethos of retribution and how consciously it stylizes all the subtitles when Keanu Reeves speaks in any of the 40 languages his character appears to know. As I mentioned earlier, Max Payne 3 cribs most of its aesthetic and a bunch of its narrative straight from this movie, probably the most peculiarly specific homage to a movie in the medium’s history.

Out of nowhere, Netflix ordered a TV series adaptation of Man on Fire last year. Even if it does manage to revive the property, I doubt it’ll look anything like Scott’s film: A reeling, vicious mini-genre unto itself.

Kenneth Lowe is the sheep that God lost. You can follow him on Twitter @IllusiveKen until it collapses, on Bluesky @illusiveken.bsky.social, and read more at his blog.