Time Capsule: John Prine, Sweet Revenge

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at John Prine’s 1973 country breakthrough, in which he and producer Arif Mardin assembled a tight 22-piece session band and built out the most ambitious and densest LP of the singer-songwriter’s then-young career.

Music Reviews John Prine

John Prine’s self-titled debut album remains a bulletproof masterpiece. Nobody has any qualms about that—or, at least, I don’t think anyone has any qualms about that. That eponymous introduction, released in October 1971 through Atlantic, has what I think are seven of the greatest folk songs ever penned on it (“Illegal Smile,” “Spanish Pipedream,” “Hello in There,” “Sam Stone,” “Paradise,” “Angel from Montgomery” and “Donald and Lydia”). The remaining six tracks are, in their own extensions of uniqueness, quite perfect, too. When the Paste music staff compiled a list of the 100 greatest debuts of all time, John Prine came in at #23—and, with each passing day, soars up my own personal list. But, when you make such a brilliant record on your first go, assembling a catalog that reaches the same heights can be a daunting task. Commercially—and, arguably, critically—Prine never really returned to the top of the mountain he’d seen via the album he named after himself. And such a singularity has led to his third LP, Sweet Revenge, often remaining overlooked and underloved. But the thing no one tells you is that Sweet Revenge is some of Prine’s finest work. You just have to go find that truth out on your own.

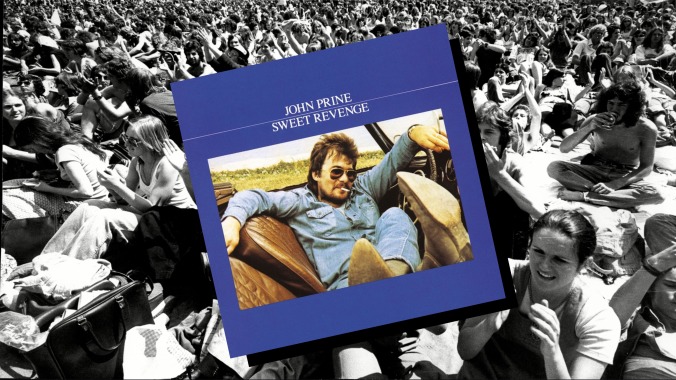

On the cover of Sweet Revenge, Prine sits—clad in denim head-to-toe—in his 1959 Porsche, flaunting his first big purchase after getting some of that Atlantic Records money. Likewise, the songs on Prine’s 1973 third outing fill out like someone with a budget to spend. For the project, he and his longtime producer Arif Mardin assembled a 22-piece band of country, rockabilly, rock ‘n’ roll and soul session musicians and completely upended any preconceptions about Prine and the simplicity of his guitar-and-microphone folk music. No, Sweet Revenge was Prine’s multi-dimensional mission statement—he wasn’t just the offspring of the protest singers who came before him, nor was he moonlighting as a comedian. Instead, Sweet Revenge posits one resounding fact: There’s never been anyone quite like John Edward Prine.

Sweet Revenge begins with its namesake, a two-and-a-half-minute country-rock crooner that finds Prine establishing himself, immediately, as a new vocal force. He was no longer just a folk singer with a guitar and a grin; it was time to level up from his singer-songwriter roots to something filled out, soulful and brand new. “Sweet Revenge” introduces Reggie Young’s lead electric axe, which bustles like a hot rod without rumbling like a freight train, and Cissy Houston can be heard singing harmonies—but there are moments where her lilt can’t help but command the full attention of the listener. If Prine is the fauna then Houston—a former member of Elvis Presley’s Sweet Impressions backing choir—is the flora, and “Sweet Revenge mirrors the Southern-style blues-rock precision embodied in something like Dylan’s “Forever Young,” but Prine was never one for mimicry—letting his edge-rough baritone ham up into a generous, badass octave with the emotional thud of a church-pew hymnal.

Prine uses the opening chapter of his third record to level some poetic jabs at the critics who were less than enthused about his last project, Diamonds in the Rough, through his own personal letdowns—leading to the “Take it back, take it back / Oh, no, you can’t say that / All of my friends are not dead or in jail / Through rock and through stone, the black wind still moans / Sweet revenge without fail” chorus that registers more like a proclamation more than it does a dismal. “I caught an aisle seat on a plane and drove an English teacher half-insane, making up jokes about bicycle spokes and red balloons,” he sings in the second verse “So I called on my local DJ and he didn’t have much to say, but the radio has learned all of my favorite tunes.” The former postal worker, Prine, wasn’t the folk darling with a Billboard 200-charting album anymore. It was time to scrap.

“This is the best organ donor campfire song I know,” Prine once said about “Please Don’t Bury Me,” one of the catchiest country tunes of its era. Initially written with a character named Tom Brewster in mind, Prine wanted to consider a man who dies but shouldn’t and, once the angels send him back to the living, he’s so mangled he has to spend his next lifetime as a rooster. “I ended up trashing that whole part and came up with this idea of the guy just giving all of his organs away,” he said. With one of his greatest choruses in hand (“Please don’t bury me down in the cold, cold ground / No, I’d rather have ‘em cut me up and pass me around / Throw my brain in a hurricane and the blind can have my eyes / And the deaf can take both of my ears, if they don’t mind the size”), Prine revels in his 10-layers-thick melody and harmonizes with Raun MacKinnon while standing on an arrangement not alien to the pleasures of honky-tonk bars and dancehalls. Prine’s brother Dave plays a mean and talkative dobro here, too, laying a contour to “Give my stomach to Milwaukee if they run out of beer”—which remains one of my favorite Prine lines. Oh, and the nod to Johnny Cash’s “Give My Love to Rose”—a tune about a dying man—is a fun Easter egg to absorb at the end of verse three.

Cue Jerry Shook’s harmonica pulls, David Briggs’s organ and that signature folk musician-on-a-mountaintop guise of electricity from Prine on “Christmas in Prison,” which is a tender portrait of one worthwhile day in the slammer—where the song’s protagonist grows homesick for his lover while spending the holidays locked up. In the first verse, we get that sense of humor that only Prine could pull off—where he sings “We had turkey and pistols carved out of wood” in such a way that suggests the meat and the guns were both made of wood. But “Christmas in Prison” isn’t all smiles, as there’s a devastating pulse fluttering into lines like “I dream of her always, even when I don’t dream,” “Her heart is as big as this whole goddamn jail” and “I’ll probably get homesick / I love you, goodnight.” I return to Sweet Revenge often because it’s the moment in Prine’s catalog where he really spins choruses out of silk; “Wait awhile, eternity / Old mother nature’s got nothing on me / Come to me, run to me, come to me now / We’re rolling, my sweetheart, we’re flowing, by God” is so beautiful you might forget just how bewitched with heartbreak it is.

While most of Sweet Revenge was recorded at Quadrafonic Sound Studios in Nashville and Atlantic Studios in New York, “Dear Abby” was captured live at State University in New Paltz. A studio version cut with the Sweet Revenge band does exist, but Prine himself admitted it never grasped the humor its writing demanded. “That was the power of the song, in the way people would turn their heads the minute I’d get to the first verse, the first chords,” he said. “My feet are too long, my hair’s falling out and my rights are all wrong,” Prine croons in that first verse, with a tinge of self-deprecation set aglow with charm. “My friends, they all tell me that I’ve no friends at all.” Revisiting “Dear Abby,” you can hear just how that candid wit has gone on to influence someone like Chris Acker, whose song “Panicked & Paralyzed” remedies a belly-aching laugh through a similar musical effigy in the name of going bald. The whole track—which features just Prine and his six-string—is rife with lyrical hits, but none stick with me quite like “Every side I get up on is the wrong side of the bed / If it weren’t so expensive, I’d wish I were dead.”

John Prine and his band kick the door back open again on “Often is a Word I Seldom Use,” which features a horn arrangement from Mardin and a seam-ripper of a solo from Young. But don’t let any of that distract you from Bill Slater and Ralph MacDonald’s percussion, which boasts a cymbal-oriented backdrop that crashes with the delicateness of a butterfly wing. “I’m cold and I’m tired and I can’t stop coughing long enough to tell you all of the news,” Prine sings out. “I’d like to tell you that I’ll see you more often / Often is a word I seldom use.” In terms of artistic growth, “Often is a Word I Seldom Use” makes good on showcasing Prine’s—as the tune arrives on the tracklist engrossed in a full-bodied mirage of aces musicianship on-par with the most top-drawer session albums of the era and the one preceding it.

Too, “Onomatopoeia” sounds like something cut from the excess of a Jerry Reed record, and it’s as fun as its title suggests. When Prine is having a blast on the mic, there’s a color to his music that is undeniable and a damn hoot. “We’re gonna rope off an area and put on a show from the Canadian border down to Mexico,” he sings. “It might be the most potentially gross thing that we could possibly do.” It’s an ode to nonsense or, as Prine says in the outro, “speaking in a foreign tongue.” It’s moments like these that make me believe that Prine’s lyricism is the eighth wonder of the world.

“Grandpa Was a Carpenter” finds Prine returning to the “Donald and Lydia” corridor of his narrative universe, as the track tells a life’s story from the perspective of someone who only caught a fragment of it. It’s a time capsule of a track, with Prine’s protagonist focusing on his grandpa’s eccentricities—like a brown necktie and matching vest, wingtip shoes—and their memories together—like going to church together. “Grandpa was a carpenter, he built houses, stores and banks / Chain-smoked Camel cigarettes and hammered nails in planks,” Prine sings. “He was level on the level, shaved even every door and voted for Eisenhower ‘cause Lincoln won the war.” The real gem of the track, though, comes at the end of the third verse, when our storyteller admits that his grandma “used to buy me comic books after Grandpa died.”

Tucked into the back-half of Sweet Revenge is one of Prine’s greatest songwriting feats: “Mexican Home.” Written after his father died right before John Prine came out, the song is a soulful elegy for the Prine family’s fallen patriarch. But this track refuses to lament, never dwelling on the grief through solemn soundscapes. Instead, lines like “the sun’s going down and the moon’s just holding its breath” and “waiting for that sacred coal that burns inside of me, and I feel a storm all wet and warm not 10 miles away” and “heat lightning burned the sky like alcohol” are among the most vibrant and touchable in all of Prine’s catalog. Throw in a horn arrangement from Mardin and backing vocals from Houston, and “Mexican Home” excels in the pathos of its own tragedy and time-honored parental love.

Prine returns to the finger-picked gentleness of his first two albums on “A Good Time,” but this time with a few extra pickers beneath his wings—namely Grady Martin and Steve Goodman, who turn angelic chords into singing voices. Here, Prine reckons with time not being as cyclical as the clocks prescribe them to be—that there is value in taking it slow and spending time with someone you’re fond of. “You know that I’d survive if I never spoke again, and all I’d have to lose is my vanity,” Prine sings in the second verse. “But I had no idea what a good time would cost ‘till last night, when you sat and talked with me.” But what “A Good Time” brings back to the table is that gravel-worn voice that made Prine a folk mastermind in the first place in 1971 and puts it on thoughtful display—as it unravels into a three-part acoustic guitar solo before the third verse shoulders the track to a conclusion.

Sweet Revenge closes with the riot of “Nine Pound Hammer,” an uptempo railworker song dating back to the 1870s. It’s a tune that’s been covered by everyone from Scott McGill to Mississippi John Hurt to John Fahey to Lead Belly to Odetta. Prine’s rendition, however, is the best—but that’s largely because it’s one of the best-sounding recordings of it we’ve got. The song’s imagery takes inspiration from the story of John Henry and is coupled with vignettes of wayward travel and romance—and, certainly, Prine couldn’t let a record off without a little commentary on class. “I’m going to the mountain just to see my baby, and I ain’t coming back,” he sings. It’s a labor anthem—punctuated by the line “And when I’m long gone, you can make my tombstone out of #9 coal—that Prine makes soar atop the chaos of country jamboree ecstasy.

Upon its release, Sweet Revenge would peak at #135 on Billboard’s Pop Albums chart—Prine’s lowest-charting album until Pink Cadillac in 1979. Stepping away from the protest of his former records, Sweet Revenge marks the songwriter exploring the exercise of telling tales for the sake of finding a light at the center of each track. There’s a softness embedded even in the more raucous chapters, as the textures and arrangements expand across the 12 songs without losing the hardened edge that fuels the fire in Prine’s creative, humorous, poetic heart. Taking the ingenue of John Prine and Diamonds in the Rough and plugging them into vivid, fast-paced country licks, Prine separates himself from the standstill folk progenies with a mature selection of swinging outlaw brilliance, and you can hear that modernity present still in the 21st century in the work of Acker, the Deslondes, Tré Burt and Hayes Carll. In 1973, Prine broke away from the mold, denouncing cynicism as a requisite for folk music. The result of such rebellion lives right there in the title-track: “Sweet revenge will prevail without fail.”

Matt Mitchell reports as Paste‘s music editor from their home in Columbus, Ohio.