The Seductive Paradox of Morrissey: The Smiths’ Meat Is Murder At 40

Steven Patrick Morrissey is an unpleasant person. We can say that now, 40 years since the release of Meat Is Murder, his band’s second record, with complete confidence. He is a battle-hardened culture warrior of the right wing, a man whose political views have slipped far beyond the point of contrarianism into straight-up chauvinism. The complication is that, despite all the terrible stuff he believes and advocates for, Morrissey also happens to be one of the great songwriters and singers of his—and any—generation. He is an artist of profound wit and insight, someone who bears a particular knack for tapping into the sensitivities of the abused and alienated and making them feel seen. He is, plainly, a crooning, seductive paradox.

I arrived at the Smiths fairly late in life, long after the evidence of Morrissey’s shit politics had piled up beyond the point of plausible deniability. Aged 18 or 19, I was properly introduced to them by a friend, who, in the old-fashioned style, lent me a plastic bag full of CDs, of which one was the Sound of the Smiths compilation. I liked it well enough, but did not yet love it, probably due to the fact that, at that particular point, I had only recently discovered the joys of dance music and clubs with low ceilings. I had no need, during those hyperactive days of house music and disco treats, of a dour man’s declarations, set over Johnny Marr’s jangly guitars, of how bloody sad everything is, but that duly changed as life ground on. That little summer of love is long gone, and now, a decade or so later, Morrissey’s exquisite misery often hits just right.

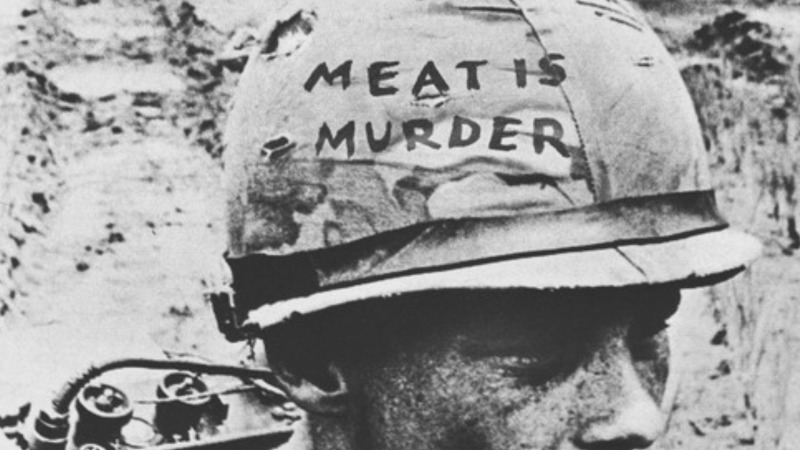

Meat Is Murder, the follow-up to the Smiths’ self-titled debut LP, arrived smack in the middle of the 1980s, on February 11, 1985, which is a fact I’ve always found surprising. The Smiths never sounded to me like an ’80s band; they seemed, to the contrary, older, and entirely antithetical to the synthesizers and glamorous sense of fun I tend to associate with the decade’s music. They always seemed so serious, which, given how funny Morrissey’s writing can be at times, probably isn’t fair, but, with an album title as bleak as Meat Is Murder, it’s an understandable interpretation.

The title track, which appears at the very end of the record, is certainly intended to be serious, but it is, too, probably the weakest of the lot, even if its intentions are admirable. “Meat Is Murder” is a jarring soundscape of violence, bookended by the cold din of buzzsaws and cattle screams, but, as a song, it just doesn’t sound great and its message never quite lands. As someone who flits between vegetarianism and carnivorism every few years, the song has never struck me as an especially persuasive call to reject meat. My meat-eating stupor has never been shaken by moralistic lecturing, nor by illustrations of the incomprehensible violence it entails, but, rather, by the experience of spending time in the countryside and actually being among those animals we love to eat. It is when I see mother cows so obviously express affection for their babies, or when I watch lambs skip about and race each other, that I actually snap out the self-imposed numbness required to eat animals. It is the realization of their joy, not their suffering, that most drives me to empathize, and the song, for perfectly understandable reasons, has no interest in evoking joy.

Morrissey is more adept at inducing empathy for other people. Where his depiction of the violence done to animals is too great and broad to truly land with me, the ordinary human-on-human violence he sings of throughout the album hits closer to home. Meat Is Murder’s first song—a hard, cool slap to the face, if ever an album opener could be—is “The Headmaster Ritual,” an almost Dickensian tale of cruel, military-like teachers in bleak schools subjecting their students to thwacks on knees, knees to groins, elbows to faces. The humdrum violence Morrissey sings of was a very real part of schooling once upon a time, but not one that I, a soft, delicate millennial, ever experienced. Yet the Smiths have this wonderful ability to, through both the music and the poetry of Morrissey’s words, provoke the pleasure and pain of one’s memories, even if the content of the song and the listener’s memories don’t quite align. Their music taps into a well inside us which shouldn’t necessarily even be there.

I did not go to an English school of the mid-20th century, where teacher-commanders worked through the frustrations of their sexless marriages by physically beating their students. But still I respond to the “Headmaster Ritual,” recalling my own days trapped inside Irish schools of the 2000s and early 2010s. There were no beatings there, but I recognize well the “belligerent ghouls” who are “jealous of youth” that Morrissey evokes in the song. These were hostile bastards at the head of plenty of my classrooms, who, but for the good grace of modern child protection laws, would have taken great pleasure in thwacking young knees and elbowing young faces. Some of our teachers were nice, most were indifferent, but a few were cruel fuckers—vindictive bullies, sociopaths and a couple of racists, too.

I, for the most part, kept my head down and checked out during most lessons, itching to get home, away from the pent-up misery of the place, and into my bedroom, where I could freely pursue release through music and excessive masturbation. When Morrissey sings, “I wanna go home / I don’t want to stay,” these are the grey memories of tedium and loneliness that he draws to the surface. In “Barbarism Begins at Home,” he, again, explores the violence that children can have done to them by adults, but, this time, he situates the tale within the family home. Morrissey has the good sense to recognize the damage such cruelty does to kids, and, consequently, he asserts that “unruly boys who will not grow up” and “unruly girls who will not settle down,” should, rather than receiving “a crack on the head,” instead “be taken in hand.” It is a call for compassion, an acknowledgement that treating young people with care, as opposed to beating them into submission, is a more effective way of reaching them, a pertinent point in today’s particular social climate.

A moral panic is beginning to swirl around young people. In the United States, it has centered around the fact Trump made big gains with young men in the election, while, in the United Kingdom, it has come in response to a recent survey claiming a majority of Gen Z want their country to become a dictatorship. The British comedian David Mitchell rather neatly illustrated the tone of the discourse that has since followed by, in his Observer column, labeling Gen Z as “fucking morons,” which is the centrist op-ed writer’s equivalent of “a crack on the head.”

The trends, clearly, are ominous. A lot of boys and young men have become dangerously alienated within our societies, and the Trumps, Andrew Tates and countless other ghouls of the internet have been on-hand to exploit their pain and humiliation. But for the rest of us, condescending these young people and demonizing their whole generation is hardly a remedy. This isn’t to say we should accept a growing misogyny among young men, but effective opposition will require a degree of compassion. There must be attempts made to understand why these people are so fucking angry, because, without that understanding, there will one day be no reaching them at all.

That a message to this end can be extracted from the 40-year-old words of Morrissey is a strange thing. Throughout Meat Is Murder, we repeatedly find him taking the side of the downtrodden, be it the young people suffering under the brutal hierarchies of the education system and the patriarchal family, or the animals who are so hungrily slaughtered in pursuit of their flesh. Morrissey mocks the oppressors throughout the record—“I’d like to drop my trousers to the Queen”—and, at the heart of it all, he never quite surrenders to the despair he so obviously feels. Even he, in this world of violence and alienation, holds that his “faith in love is still devout.” But it’s tricky, as a listener today, to be able to square all that with the toxic figure we now know Morrissey to be.

Morrissey has, since the glory days of the Smiths, come to represent the side of hate. He has spoken in support of Tommy Robinson, one of the UK’s most prominent Islamophobic, far-right figures, and publicly backed the For Britain Movement, a now-defunct far-right political party set up by a woman known for peddling the great replacement conspiracy theory. He has pondered aloud that “you can’t help but feel that the Chinese are a subspecies,” because of their “treatment of animals,” and, predictably for a man of his ilk, he has droned on about the loss of “British identity,” which has, as he sees it, become diluted by the scourges of immigration and multiculturalism.

This sort of rhetoric has ratcheted up in recent times, but none of it is especially shocking when you read some of the stuff Morrissey said during even the early part of his career. He always showed off a reactionary streak, as in the ’80s, when he characterized reggae music as “vile” and declared that he detests “black modern music” in general. “Obviously,” he told the one-time music magazine Melody Maker, “to get on [British chart music TV show] Top Of The Pops these days, one has to be, by law, black.”

This side of Morrissey is, bleakly, not especially unusual in today’s United Kingdom. Pick up a British tabloid newspaper, or switch on breakfast TV, and you’ll surely encounter the paranoid, spluttering shit takes of a middle-aged white man bemoaning the loss of good old English values to woke mobs, bloody trans people and job-stealing immigrants. There is an entire media industry composed of these purple-cheeked flesh bags of frustration, dedicated wholly to pumping out bigoted bile, which, regrettably, seems now to be swallowed down by more and more people. Recent polling has indicated a surge of support for the far right in the UK, especially in the deindustrialized north of England, which is where, not at all coincidentally, Morrissey hails from.

There is a sharp economic divide running through England today, with, in broad terms, the south being considerably more affluent than the north. Both main political parties, the Conservatives and Labour, are widely seen as abandoning the northern side of the divide, with the sitting Labour government doing absolutely nothing at present to dispel the notion. Into this vacuum of leadership up north has stepped the far right, which, like Morrissey, celebrates and pines for an imagined past of good old English glory, before immigration and wokeness ruined everything. It ignores the real reasons for the country’s decline—like the purposeful dismantling of the welfare state and the capture of the economy by private equity—and instead blames the poor, the disabled, the foreign, the queer, the female, the Muslim, the Black. More and more people, with no other alternative in play, seem to be falling for the shtick.

Many of those lured into supporting the far right have often correctly perceived that something has gone badly awry within their societies. The tragedy is that, through lies and distraction, they end up blaming the wrong people for the real issues they face. Perhaps that’s part of what makes listening to Meat Is Murder today so compelling, even with the full knowledge of the politics Morrissey holds. The album, at its best, reveals its lyricist at his most humane and gracious, a man alert to the suffering of others, but, 40 years on, we know he has badly lost his way somewhere along the line. It’s like a morality tale for the country as a whole. Morrissey’s descent into reactionary and confused thinking is, sadly, all too ordinary in a contemporary Britain dazed by the speed of its own decline.

On the other hand, the plain fact is that Morrissey is an exquisite songwriter. Perhaps I am searching for a grand, meta narrative to justify enjoying—loving—the music and stories of a man I otherwise find detestable. It’s uncomfortable to idolize people we know to be hypocrites, but it is a discomfort I find myself living with. I cannot separate the artist from the art, but that doesn’t mean I’ve rejected the art itself. It’s a paradox that cannot be solved: Morrissey, the songwriter and performer, is a genius, but Morrissey the person is pathetically, tragically, flawed.