The Beach at 25: A Youthful Transgression for Leonardo DiCaprio

Imagine if a movie in 2025 made nearly $300 million worldwide against a budget of less than $100 million. Now imagine that this non-sequel movie was sold not on action spectacle, superheroes, a bestselling novel, or a packed ensemble of familiar faces, but rather a solitary movie star whose last starring role was two years earlier. Today, this would be considered, if not a miracle, at least a semi-magical anomaly. Even a decade back, it would be considered very impressive. But 25 years ago, when The Beach was released in theaters as the first “real” follow-up to Leonardo DiCaprio’s superstar-making turn in Titanic, it was a massive disappointment. (The above-mentioned numbers were “just” $150 million and $50 million, respectively; honestly, even unadjusted for inflation, they would be considered a success for a young star in 2025. Challengers would have been delighted with those global numbers.) That doesn’t seem especially fair, but it is appropriate that this particular movie would somehow qualify as both an unlikely accomplishment and a crushing disappointment. That’s The Beach all over.

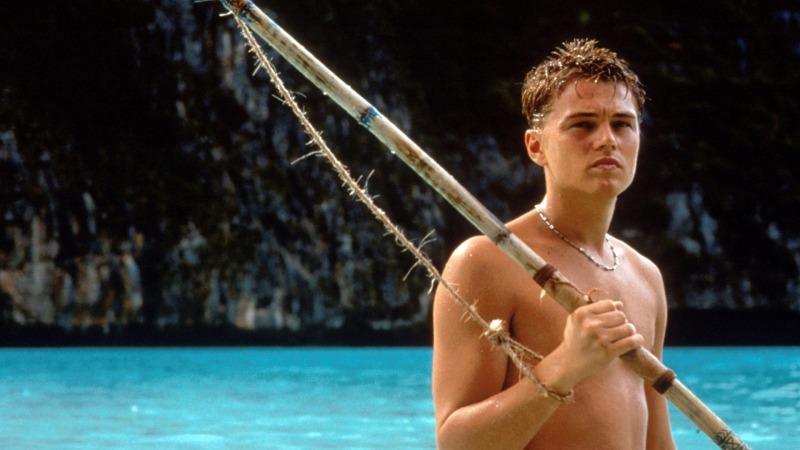

It’s also a project both perfectly suited for DiCaprio, then in his mid-twenties, and an odd fit given its origins. The film was adapted from a novel by Alex Garland – yes, that one – by filmmaking team Danny Boyle (director), Andrew Macdonald (producer), and John Hodge (screenwriter), who made Shallow Grave, Trainspotting, and A Life Less Ordinary in quick succession. Those three all starred Ewan McGregor, who assumed the leading role in The Beach would be his as well. But Boyle could receive more generous financing with a bigger name, and lucky for him, DiCaprio showed interest in the project as his true follow-up to the biggest movie of all time (The Man in the Iron Mask, filmed earlier, was a hit while Titanic was still in theaters in the spring of 1998; Celebrity, released that fall, gave him a small role as, essentially, himself). DiCaprio’s youthful, insouciant hunger onscreen makes him good casting as Richard, an American traveling through Bangkok and desperate for a genuinely new, non-tourist-trodden experience. But the poor-man’s-Trainspotting narration, where a restless Richard verbally casts about for a worldly philosophy, would probably just plain sound more convincing coming from McGregor. (Maybe this is an American’s own anti-American, pro-Scottish-accent bias.)

It’s also – maybe, admittedly, too easy – to picture McGregor reuniting with his Trainspotting co-star Robert Carlyle in the early scenes, where the latter plays a fellow traveler, drunken and ranting, staying at the same Bangkok hotel, who tells Richard of a secret island in the Gulf of Thailand. He even draws him a map, seemingly just before committing suicide. Richard, blessed with a youthful callowness, takes this harrowing experience as an opportunity to invite a French couple down the hall to join him on a crazy journey (mostly because he has the hots for Françoise, played by Virginie Ledoyen). They agree, and eventually the trio does make their way to a hidden oasis, discovering a full-on miniature society led by Sal (Tilda Swinton in an early role). Ample sun, gorgeous blue water, white-sand beach, fun and games, communal living, shared chores, and only the occasional two-person trips to the mainland for supplies, otherwise cut off from the rest of civilization… it is, for reasons he’s only half-successful at articulating, Richard’s paradise, and the others’ too. Were The Beach made even a little bit further into the 21st century, it would almost certainly need to incorporate some kind of unplugging, anti-tech sentiment; at the turn of the century (the film was shot in 1999), the fact that the island has no phone or internet isn’t even mentioned directly – though by opting out of Y2K paranoia entirely, it becomes its own entry in that period’s canon of technological ambivalence.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-