Time Capsule: Isaac Hayes, Hot Buttered Soul

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Isaac Hayes’ transformative 45-minute, four-song second album. The results were not only more dynamite and dramatic than the clean-shaven #1 hits coming out of Motown before, during and after, but they were strange, novel takes on a funk genre not yet fully borne from soul's most progressive idealists.

I heard Isaac Hayes long before I knew who Isaac Hayes was. It was while watching The Blues Brothers, and it was while watching 90210 re-runs. There he was—or, there his writing was, as “Soul Man” and “Hold On, I’m Comin’” went into view. Hayes and David Porter became something of a songwriting team for Stax Records in the early ‘60s, becoming the lyrical hot-steppers while Booker T. & the M.G.’s tracked all the instrumentals for Sam & Dave, one of the most successful soul duos of all time—a duo who, in the eyes of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, “brought the sounds of the Black gospel church into pop music with their call-and-response records,” records covered in Isaac Hayes’ fingerprints.

Hayes was born into a sharecropper family in Covington, Tennessee, and raised by his maternal grandparents after his mother passed away and his father abandoned him and his older sibling. He was a farmer in Shelby and Tipton counties, but by age five he taught himself piano, organ, saxophone and flute. Hayes sang at his church. After getting his high school diploma in Memphis at age 21, colleges and universities offered him music scholarships, but he worked at a meat-packing plant in the city instead. He’d moonlight at juke joints in the evenings, playing right there in Memphis or, sometimes, going to northern Mississippi. Famously, he became a regular singer at Curry’s Club with Ben Branch’s house band backing him up.

The soul man’s debut album, Presenting Isaac Hayes, which was co-produced by two M.G.s, Al Jackson Jr. and Donald “Duck” Dunn, held promise but sold horribly. “Precious, Precious” stood out, for it being a 19-minute jazz composition later diced into a three-minute single that didn’t chart. When Stax lost its back catalog to Atlantic, all of the signed artists had to record new material to replenish the label’s wealth. That’s when Hayes, splitting time between Ardent Studios in Memphis and Tera Shirma Studios in Detroit, went to work with Al Bell. Elsewhere, M.G.’s guitarist Steve Cropper was doing the same. Bell granted Hayes full creative control over his follow-up, and he came back with a 45-minute album featuring four songs that were this spectacular collision of psych-soul, prog-funk, blues-rock and gospel. The jazz habits of Presenting were stylistically gone but remained in the pillars of his symphonic risks.

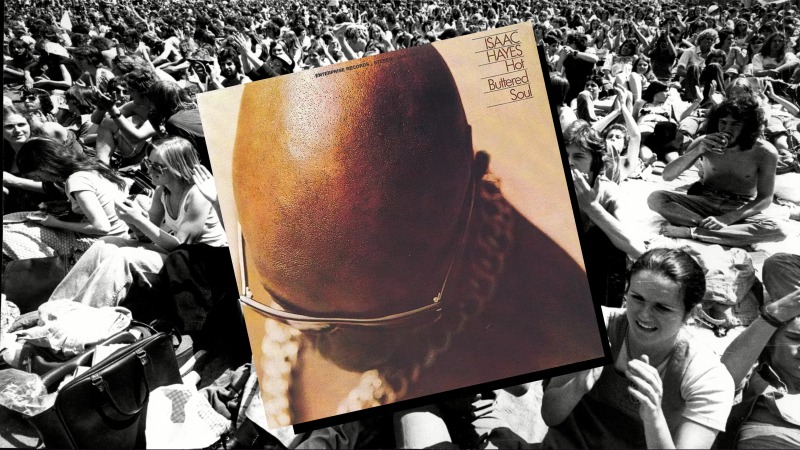

Hot Buttered Soul came out on Stax’s Enterprise subsidiary and became one of the greatest soul albums of both its time and all time. Without it, Hayes doesn’t go on to make his magnum opus, Black Moses, or write the music for Shaft, thus stripping us of one of the most culturally important soundtracks in the history of cinema. The coolness of a record like this begins with its cover, which features a bald, Cuban link chain-wearing Hayes tilting his head towards the camera, veiling his big-rimmed sunglasses out of focus. While making his sophomore effort, Hayes figured out what formula might propel him out of the commercial failures of Presenting. He asked the Bar-Kays to be his backing band, and he called upon pianist Marvell Thomas (who would earn a co-producer credit for his contributions) to fill out the ensemble. During the recording sessions, Hayes played a Hammond organ and tracked his singing live while simultaneously conducting the Bar-Kays. Detroit arranger Johnny Allen was hired to compose the string and horn parts; Russ Terrana engineered the final mix, filling in the melodies’ missing piece—a radically proficient orchestra. Hot Buttered Soul also featured pre-delay reverb, which engineer Ed Wolfrum would later employ on Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. Terrana would never be too far away, either, using Hot Buttered Soul as a launch pad into his most famous role, as an engineer at Motown Records.

The only song on Hot Buttered Soul penned by Hayes was “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic,” a nine-and-a-half-minute, stupefying fashion of funk and decade-spanning cultural prisms. I hear this song unfurl through the tempo shifts and genre swaps and can pinpoint the influence of James Brown’s live recordings and Ray Charles’ Big Band, ABC-Paramount performances. The album itself gave soul music a brand new vocabulary, and it gave an opportunity to experiment to the genre’s next generation, especially Curtis Mayfield and the Ohio Players. I’m not saying that Isaac Hayes invented the 10-minute soul song, but no one else from his generation made it sound as cool. “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic” is like stepping into a museum full of artifacts it created.

Hot Buttered Soul’s song selection is fascinating, as the Jimmy Webb-written “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” and the Burt Bacharach- and Hal David- created “Walk On By” bookend the project. Perhaps that is where Hayes’ genius best strikes, as country and lounge-pop compositions get so completely rewired by the madman multi-instrumentalist that they sound brand new. I mean, “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” first made famous by Glen Campbell in 1967, sounds virtually unrecognizable in the company of Hayes’ reconceptualizing, transforming from a 2:42 runtime when Campbell is singing it into an 18-minute epic—with Hayes turning it into a spoken-word joint suspended in mid-air by one throbbing, looping bass line and a droning organ. He uses this monologue to give a backstory to the actual song he’s about to perform, in which a husband caught his wife cheating and drove away in a ‘65 Ford. As the 10-minute mark creeps in, Hayes begins to rhapsodize, and Allen’s string-and-horn ensemble slowly colors the foreground of his voice. This is when “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” channels the bottom-of-your-gut singing that someone like Otis Redding institutionalized years prior. The last five minutes of “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” are its best, as the symphony crests into this mirage of trumpets that reach a far greater mood than anything I’ve ever categorized.

As a contrast, “Walk On By” is immediately pretty, buoyed first by Allen’s orchestra and then by a back-and-forth, instrumental call-and-response featuring the stone-cold guitar playing from Micheal Toles (that feels far more akin to the culture’s budding pockets of hard rock than Steve Cropper’s session-famous precision), a solo from Funkadelic’s Harold Beane and Hayes’ heavy-fingered organ medleys. The Bacharach and David tune first got popular in 1964 when Dionne Warwick sang it, charting at #6 on the Hot 100. But the funk vamp Hayes and his counterparts is immortally dense, tectonically satisfying and improbably perfect—to the point that it has become one of rap music’s strongest reference points, getting sampled by everyone from the Notorious B.I.G. (“Warning”) and 2Pac (“ME Against the World”) to MF Doom (“Dead Bent”), Wu-Tang Clan (“I Can’t Go to Sleep”) and Beyoncé (“6 Inch”).

Hayes’ impassioned take on Charles Chalmers’ and Sandra Rhodes’ five-minute “One Woman” is Hot Buttered Soul’s one moment rid of instrumental excess and exhaustive runtimes, positioned as the calm before the storm of “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”’s stretched-out hugeness. Considering the proverb of infidelity that “Phoenix” evokes out of Hayes, hearing him get spiritual about monogamy one track earlier makes for a wonderful converse. It’s the sharpest, most-imposing part of the album and, just like “Walk On By,” “One Woman” begins as a piano ballad before exploding into a Bar-Kay-touched, orchestra-led rupture of weeping harmony vocals and sweet, heraldic brass.

Upon its release in June 1969, Hot Buttered Soul topped Billboard’s R&B chart and peaked at #8 on the Top 200. It later went to #1 on the publication’s jazz chart, which angered the genre’s top names, including Miles Davis. Two heavily edited singles, “Walk On By” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” reached the Hot 100’s Top 40. Hayes’ penchant for long—and I mean, long—songs in a genre lionized for its accessible, chart-ready, three-minute singles made him an outlier. Looking at Hot Buttered Soul nearly 56 years after its initial release, and you can see just how in-between everything Hayes was, as these four songs were not only far more dynamite and dramatic than the clean-shaven #1 hits coming out of Motown before, during and after, but they offered strange, novel takes on a funk genre not yet fully borne from soul’s most progressive idealists.

Hayes’ ability to pull off 12-minute and 18-minute tracks on a popular soul record during the height of rock and roll’s dominance in music’s late-‘60s nomenclature made him one of the most consequential figures in the ever-changing industry, despite Rolling Stone declaring him the “enemy of all that was good about soul music” in the early 1970s. Looking at the landscape of soul music in 1969 especially, Hot Buttered Soul was singular, rivaled only by Sly and the Family Stone’s Stand and the Isley Brothers’ The Brothers: Isley. And I see a world where Hot Buttered Soul helped create a not-so-green and starry-eyed Marvin Gaye, whose 1970s compositions, especially I Want You, rollicked with the same kind of limitless grandiosity as Isaac Hayes’ turn-of-the-decade triumph. It’s funny what doorways commercial failure, Stax fumbling their own catalog, and the magic of Johnny Allen’s sinfonietta can open if the right man is walking through them.

Matt Mitchell is Paste’s music editor, reporting from their home in Northeast Ohio.