Fust’s Big Ugly is a Steadfast, Undying Love Song

Bookended by collapse, the Durham band’s third album is a crucial language, one voicing an undersung American existence; like the Southern Renaissance masterpieces, its content is stunningly furthered by its aesthetic form, wrought in close detail by Aaron Dowdy’s pen.

Of the writers to emerge from the Southern literary renaissance occurring through the 1920s and ’30s, Mississippian William Faulkner’s legacy looms the largest. In his cross-generational opus, Absalom, Absalom!, he famously pens a series of questions that the movement itself more or less existed to reckon with: “Tell me about the South. What it’s like there. What do they do there. Why do they live there. Why do they even live at all.” Whereas the bulk of post-Civil War Southern literary works read like love letters to an idyllic antebellum era that never truly was, Faulkner and his like-minded contemporaries accounted for the ghosts suspended in the thick, hot air; they allowed centuries of compacted grief, confusion and anger—too immense to cram within the established confines of language—to thunder and roil within their prose, inscrutable and unbounded. Postcards of a never-was paradise still circulate throughout America, but their flimsiness is stark next to the works of authors who hungered to honestly answer the essential questions about the South.

“Spangled,” the lead single and opening track on the Durham band Fust’s third album, Big Ugly, seems Faulknerian in heritage—from its title, it’s a distinctly American ghost story whose greatest accomplishment lies in casting the haunted, dirty South in a musical landscape as gritty and expansive as the place itself. Singer-songwriter Aaron Dowdy wastes no time in telling us about the South, setting a desolate mise en scène with the album’s opening proclamation: “They tore down the hospital / Out on Route 11.” On the album’s final track, “Heart Song,” his narrator falls just as that first edifice etched into song did: “I’m blacking out from living,” he confesses, his wounded exhalation fading into a woozy haze of pedal steel that hangs above a bed of grungy guitars like a weightless head over lumbering, drunken feet.

Bookended by collapse, Big Ugly is a mausoleum for small Southern bygones, wrought in close detail by Dowdy: torn-down small towns where heaven seemed in-reach, a beer-fisted past self with nothing else to hold, the cans and cigarettes that lined a shabby old convenience store’s shelves. In answering questions of Southern living, it raises an age-old, universal query: What does it mean to love people and places once they’ve become part of history, one that hasn’t quite passed? The album’s title derives from a West Virginian area based around a Guyandotte River tributary named for the crooked, “Big Ugly” creek rushing through it. A hastily assembled Internet guide to Appalachian West Virginian communities introduces Big Ugly as “one of those place names newspaper columnists grab on a slow day,” but Dowdy saw more than a conspicuous headline in the nickname—the evocative, oddly affectionate word pairing captured the essence of the songs he’d been writing: unfiltered snapshots of hardscrabble Southern living zoomed in on the people and places.

Fleshed out by a full band and esteemed guest players, Dowdy’s final compositions are, indeed, big. They aren’t always pretty, per se (although exquisite fiddle pulls and glossy keys attenuate some of the denser offerings, to an unearthly, beautiful effect), but unabated love seeps from every cranny of even the gnarliest, craggiest constructions, deluging every corner of the heart.

While not staging a strict history of its namesake, the world of Big Ugly feels just as real; its text is fictional, but so deeply and unmistakably rooted in Dowdy and his family’s homelands that the record could pass for an autobiographical concept album. The threads of the stories began unspooling from Dowdy upon his encountering a millenia-old ground gutter in Greece in 2023. It prompted a Proustian response from the homesick Carolinian, immediately conjuring the southern West Virginian territory he’d traversed with his grandmother in the prior few years, as well as the dilapidated houses he grew up around in Appalachia. Likewise decrepit fragments of history—that which are residual and that which are actively unfolding—are what ground one in the world of Big Ugly: the ditches clogged with water and debris; the non-hiring Country Boy gas station and the iffy mechanic’s lot; the flickering light in the bedroom and not-quite stale bread left on the kitchen counter. Each song is a microcosm of its own, and the anecdotes within each, if banal, are so intensely vivid that it’s challenging to imagine them having solely transpired on paper—you can almost trace the steps of every character, deepening their footprints as you meander the dirt roads winding across 11 chapters.

Surely in part due to having grown up Jewish in an often hostilely evangelical climate, as well as briefly having lived outside of the South, Dowdy is able to observe his homeland from the dual perspectives of an outsider and insider, studying the merits and flaws of its inhabitants under a microscope as they fade into the past-tense. Contrary to some of his more commercially viable Southern songwriting peers, he doesn’t treat the cozy, timeworn aesthetics of country music as a wall upon which to hang a portrait of a simple utopia—one where liquor and the Lord reign supreme. For while his dreams of the past are steeped in nostalgia, one never forgets that they are no more than that: dreams. “We can’t stop sleeping, it’s the most dangerous game to do,” he intones on the elegiac ballad “Sister,” before delivering what might be the album’s most devastating couplet: “I whisper, ‘Should we get up?’ / Why, so the pain can get up, too?” There’s often a mournful tinge to the swell in Dowdy’s heartfelt croon, such as when he recalls having learned how to hold his liquor with the Southern kids he grew up with—“It’s all we got,” he hums with melancholic hindsight. As the past and present blur on Big Ugly, so do love and grief, which seem as inextricable.

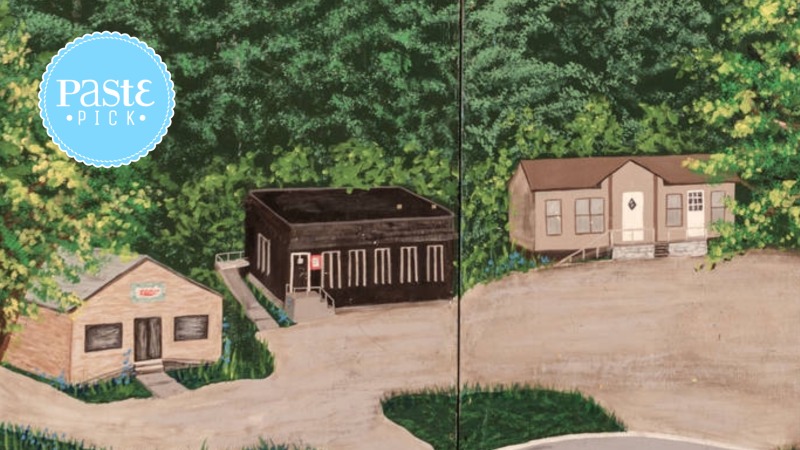

Because it is situated at the intersections between past and present, love and grief, and beauty and ugliness, Big Ugly is a thorough act of preservation. Foreshadowing this purpose is the album’s cover artwork: a soft-toned mural from a West Virginian community center—one depicting the verdant Big Ugly creek area, painted for a play in which children reinterpreted their elders’ tales. The catchiest track, the rag-tag triumph that is “Mountain Language,” offers a gesture of faith in this oral storytelling tradition—one that, Dowdy suggests, might revitalize obscure pockets of America: “There’ll be language on the mountain again,” he hopes, if only we make the effort to climb it, keeping our ears open for stories worth telling as the terrain cracks beneath our heels.

The music of Big Ugly is a crucial language, one voicing an undersung American existence; like the Southern Renaissance masterpieces, its content is stunningly furthered by its aesthetic form. “Bleached” sees Dowdy wreathed in a soft glow of synths (courtesy of the War on Drugs’ David Hartley), delicate strings and muted strumming; the quietly chest-swelling arrangement beautifully parallels Dowdy’s bittersweet memories of expired innocence. On the other end of the musical spectrum, the fried, electric riff sputtering throughout “Goat House Blues” sounds like it’s been dragged through the mud, materializing a soundscape that parallels the ruin Dowdy revels in: “Being free, it ain’t half as rewarding!” he cries out, his declaration of homeland pride prompting a gloriously grimy guitar solo. The ease with which the band (drummer Avery Sullivan, pianist Frank Meadows, guitarist John Wallace, multi-instrumentalist Justin Morris, fiddler Libby Rodenbough and bassist Oliver Child-Lanning) shifts between sparse, dusty devotionals and hearty chunks of heartland rock is a testament to their versatility, an attribute sure to cement their position among this generation’s definitive Southern rock acts. Produced by the legendary Alex Farrar (MJ Lenderman, Merce Lemon) at Asheville’s Drop of Sun Studios, each song on Big Ugly feels utterly timeless, nurtured by the past but robust enough to endure into the future. Simultaneously, they’re distinctly of this moment—one can hear Fust’s songs comfortably settle upon the mantle of modern-day classics in real time.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-