Folkfest of the North, Boston: The Happiest Place on Earth

The Folkfest of the North tour comprises a 28-city sojourn and a lineup of four acts, each as different from the rest in influences as sensibility. In this niche, they’re superstars, though they seem not to have gotten the memo.

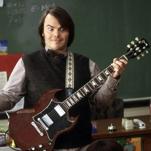

Photos courtesy of press/Folkfest of the North

It’s all fun and games in the mosh pit until someone loses an eye, excepting the kick off show for the Folkfest of the North tour last Thursday; there in the Brighton Music Hall’s snug brick embrace, they lost their lunch instead. The pit is indisputably the worst place for a metalhead to blow chunks. Imagine a child enthusiastically jumping in a puddle of fresh mud without their Wellies to safeguard them in the splash zone. Now swap “mud” with “vomit,” and “child” with “adults in sleeveless jean jackets, decorated with spikes.” The likeliest outcome is grim and gross in equal measure.

But instead of making mayhem out of a mess, the attendees formerly bullrushing each other for sport pivoted: They draped arms over shoulders, formed a circle and danced a metal show equivalent of Ring Around the Rosie, gyring with the same joyful abandon as a silt-slicked tyke. The bad news is, anybody within nasal range risked catching the wafting telltale stench of disgorged gastric acid. The good news is, they had a good time regardless, synched with the sylvan melodies and galvanic virtuosity that wed folk metal to, as well as distinguish it from, cousin sub-niches in the most brutal musical genre.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-