Nintensive Care: Why Radar Scope Is One of the Most Important Failures in Gaming History

Games Features nintendo

How did Nintendo become the Nintendo we know today? Our column Nintensive Care tracks the history of Nintendo’s videogame era and its outsized influence on games and the gaming industry. Up this month: 1980’s Radar Scope, a game that had a pivotal impact on Nintendo’s future—not because it was a success, but it was such a failure that it almost shut Nintendo of America down well before the NES even existed. Typically available only to subscribers, this month’s installment of Nintensive Care is free for all to read.

Everybody needed a Space Invaders. Taito’s 1978 game wasn’t just a hit; it’s the moment when videogames went from a novelty to a viable medium that would quickly conquer arcades and gradually develop into the multibillion dollar industry we know today. Space Invaders was the biggest thing going and every arcade and game room needed one, or something similar—which meant every company that made videogames needed a Space Invaders knockoff in their portfolio. Even a Kyoto-based playing card company that started dabbling in electronics and videogames in the early ‘70s.

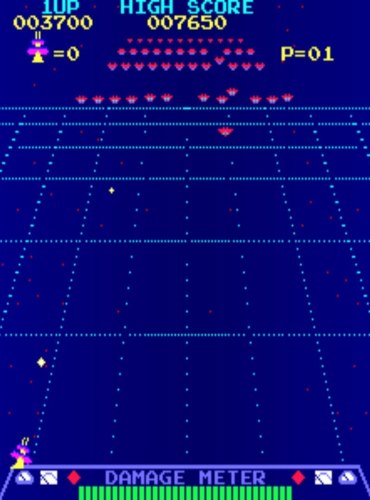

After releasing its first true videogame, Sheriff, through the publisher Sega in 1979, Nintendo focused next on their own Space Invaders riff. It would follow the basic framework of Taito’s smash, with players controlling a ship at the bottom of the screen and firing at enemies that approached from above. Unlike Space Invaders, whose rows of enemy ships moved in slow, predictable unison, Radar Scope’s bad guys would move more like the ships in Namco’s Galaxian, with circular patterns that made them harder to hit. Instead of Space Invaders and Galaxian’s flat top-down perspective, Radar Scope would use an angled grid to provide a semblance of a three-dimensional view, in what became its most unique and defining feature.

Radar Scope would also differ from Space Invaders and Galaxian in one other crucial way: it would be a massive flop that almost ended Nintendo’s expansion into America after a single game.

Radar Scope performed well enough in Japanese arcades when it came out in October 1980, but it absolutely tanked in the US. The Space Invaders fad was dead by the time the machine made its way to America two months later, killed by too many knock-offs and the arrival of newer, more complex games like Pac-Man. Nintendo of America was only able to move a third of the cabinets made for the US market, with a couple thousand unsold units cluttering up their warehouse. Nintendo of Japan rushed into developing a new game, something that could be easily swapped into unsold Radar Scope cabinets; a young artist who had worked on Radar Scope and Sheriff pitched a novel idea inspired by King Kong and starring some weird little guy with a mustache and overalls, and that artist’s first game as a lead designer helped save Nintendo from the great Radar Scope debacle of 1980. Yes, Radar Scope gave us Donkey Kong, Mario, and Shigeru Miyamoto’s career as a game designer.

Radar Scope has long been a small but pivotal footnote in Nintendo’s history. It’s the existential flop that directly led to the company’s first smash and the career of the most revered designer in games history. Its legacy greatly overshadows the game itself, which hasn’t received the regular updates, remakes, and rereleases showered upon so many of Nintendo’s games. It’s a cautionary tale and origin myth in one, with the game itself falling by the wayside and rarely being considered on its own terms today.

So what is Radar Scope like beyond the story? Did it deserve to be a flop in 1980? Is there more to it than its reputation? Would I be asking these questions if I didn’t plan on trying to answer them, like, right now? Of course not.

I’ve known Space Invaders, Galaxian, and other early shoot-’em-ups like them for as long as I’ve been playing games. I’d never played Radar Scope until earlier this year, though. And what I discovered was a game that certainly has a fair amount of flaws, but that also innovated more on the Space Invaders formula than most games of its era. I can see why it didn’t succeed as much as Galaxian or Galaga, but it maybe didn’t deserve to die the commercial death that it did.

That perspective trick is the one thing that really elevates Radar Scope above most of the competition. Its simulation of depth gives it a rhythm and sense of pressure noticeably different from the Galaxians of the world. It’s similar to what we find in 1981’s Tempest or the 1983 shooter Gyruss, but not as refined or powerful as in those two games. Space Invaders has this kind of foreboding, monolithic march—a steady sense of dread that doesn’t fluctuate that much. Radar Scope’s third-person view lets the stress ebb and flow, spiking as the enemies get closer to your ship and mellowing out as you wait for the next wave. The sweeping motions of its enemies are also more elegant than many similar games, giving Radar Scope an almost dancerly grace. Oh, and it also talks, in that too-loud, too-muffled drone of early computerized speech, like a robot version of a Charlie Brown adult; if you weren’t around arcades in the early ’80s, you probably can’t imagine how absolutely amazing it was whenever a game talked, even if you couldn’t understand a single word it was trying to say. All of these little quirks combined keep Radar Scope from feeling too much like any of the legion of Space Invaders clones cluttering up arcades in 1981, and it’s disappointing its virtues weren’t adequately appreciated at the time.

Still, it’s far from a great game. It can’t match the brutal simplicity of Space Invaders, or the vibrant colors and kineticism of Galaxian. It’s unusually drab for a Nintendo game, just a sparse blue background with an unattractive blue-green grid on top of it, and small red and yellow enemies fluttering about. It’s sluggish, one of the worst things this kind of game can be, and about as repetitive as the genre gets. The ship designs are generic and uninspired, and it doesn’t really have any of the character or whimsy Nintendo is known for. Its big selling point is its mechanical advances for the genre, but its presentation is so lifeless that its commercial failure starts to make sense. As cool as it can feel to play Radar Scope, it’s not fun to look at, and weirdly enough the graphical trick that makes the former happen—that grid—is a big reason the latter is true. Radar Scope simply doesn’t feel like a Nintendo game, and I can see why, at a time when the Nintendo name meant nothing in America, it did a face-plant in the US.

Everything that Radar Scope lacks exists in abundance in the game that eventually took root in its cabinets. Donkey Kong is infamously difficult, but became one of the biggest games ever because it’s absolutely dripping with charm and character. Radar Scope’s failure drove Nintendo to fully become the Nintendo that players have loved for over 40 years, and even though it’s a solid shooter with a unique streak, it’s easy to see why Radar Scope will always be remembered as the flop before the storm.

Senior editor Garrett Martin writes about videogames, comedy, travel, theme parks, wrestling, and anything else that gets in his way. He’s also on Twitter @grmartin.