Peculiar Plates from the Original “Meatless Monday”

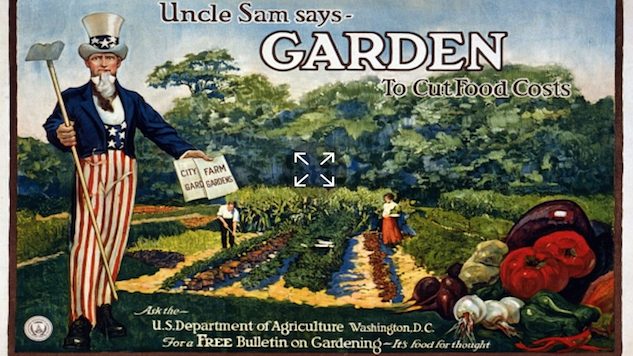

April 6 marks the 100th anniversary of the U.S.’s entry into World War I. Even though it was fought “over there” in Europe, the war had a profound effect on the daily lives of Americans, especially their diet. Our allies in France were starving, and our soldiers needed protein power. Instead of rationing on the home front, Herbert Hoover, then head of the Food Administration, tried a psychological approach, issuing posters and pamphlets that urged home chefs to use less meat. He was effectively guilt-tripping gluttonous Americans into lighter eating habits. As the Food and Victory (1918) cookbook put it, “The use of less meat in this country should not mean a hardship to our people. Indeed, most Americans have eaten too much of it.” Why not try mock oysters, i.e. boiled rice, turnip and nut balls, instead? Serve with catsup.

Hoover’s innovation—restored to public attention in 2003—was the notion of “Meatless Monday,” although, for whatever reason, they chose Tuesday to be America’s vegetarian day, alliteration be damned. The War Cook Book for American Women: Suggestions for Patriotic Service in the Home, issued in 1917 by the United States Food Administration, laid out the culinary commands: a minimum of two wheatless days (Monday and Wednesday); one meatless (Tuesday); and two porkless (Tuesday and Saturday). Further advice: “Give cottage cheese a fair trial.” For example, cottage cheese and peanut butter soup is tasty, according to Food and Victory.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-