Stolen Kingdom Entertainingly Documents the Dark Subculture of Disney Theme Park Theft and Trespassing

The Walt Disney Company has, for decades on decades, cast an outsized shadow over the landscape of American entertainment and popular culture–an aspirational ideal of sanitized Americana that ardent fans have always seen as an escape from the drudgery of a decidedly less magical real world. Much of the company’s mystique is maintained by a tight-lipped form of secrecy that permeates it from top to bottom: Disney is famously private, proprietary and litigious in both its product development and theme parks, guarding its secrets and aggressively defending its IP even when the circumstances seem absurd. The flip side to the company’s inherent shroud of mystery and cloak-and-dagger operations, though, is an inevitable, burning curiosity among a specific type of people who care about this sort of thing: The more you hide details from a Disney obsessive, the more they want to do anything to look behind the curtain. And that’s where the urban explorers and outright thieves profiled by Stolen Kingdom enter the equation.

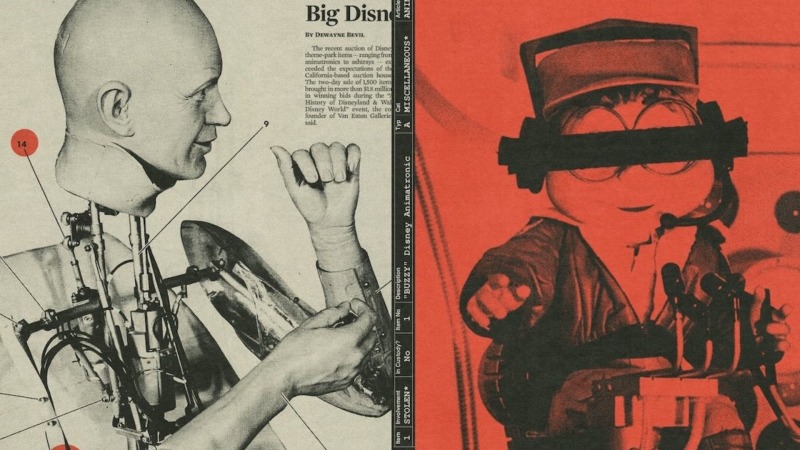

Stolen Kingdom is a new, bite-sized (a mere 75 minutes) feature documentary currently available via the Slamdance Film Festival, which revolves entirely around the subculture that has grown up around dredging up cast-off Disney theme park ephemera. Sometimes these items are obtained and preserved simply out of adoration for the company and its aesthetic, kept alive by fans who can’t let go of discontinued rides or experiences. The urban explorers who break into abandoned sections of the parks refer to these more idealistic explorers as “pixie dusters,” the contingent of true Disney fans who believe the company can do no wrong. And of course other times, items go missing because there’s serious money to be made in selling the right items to the right, equally obsessive collectors. This is of course a black market that can only exist on the back of the so-called “Disney Adults”–affluent and often childless people who spend large amounts of money on Disney fandom. You or I might not be able to imagine spending $20,000 on mothballed animatronic costumes that once graced The Haunted Mansion or Pirates of the Caribbean, but because that person most definitely exists, there will always be an incentive for criminality.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-