The Sunshine Makers

Half a century after it was banned, scientific research into the therapeutic effects of LSD has started up again, so The Sunshine Makers seems especially timely and propitious. A documentary look at Nicholas Sand and Tim Scully, an unlikely pair of renegade chemists at the heart of 1960s counterculture, director Cosmo Feilding-Mellen’s film unfolds as a more loose-limbed, affable, nonfiction Breaking Bad for the psychedelic set, if Walter White were motivated by altruism rather than righteousness and money. Even if one wishes for a bit more form and discipline to this telling, it remains engaging throughout, conveying in rich detail the sort of wild, alt-history tale of which one daydreamed while dutifully plodding through high school textbooks’ euphemistic references to “social turbulence” of the era.

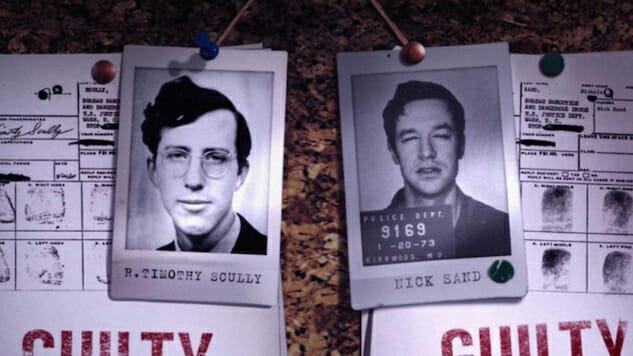

The Sunshine Makers charts the rise, fall and unlikely rebound of two science-savvy gentlemen who became drug dealers not so much by ambition as by calling—for theirs was a utopian mission to save the planet through the altered-state consciousness-raising of lysergic acid diethylamide, more commonly known as LSD. The plan, crazy as it seems, was to make enough LSD for 750 million doses—the sales of which would be enough to fund operations, but also give away massive quantities of it.

A self-described spiritual warrior for peace, the New York-born Sand is the film’s colorful leading man, shown practicing naked yoga as frequently as his more conventional interview cutaways. Resembling a more squat, roly-poly Werner Herzog, with the raised-brow impishness of Errol Morris, Sand is an LSD evangelist, absolutely certain of the drug’s ability to melt away prejudice and change the world. San Francisco-born Scully, meanwhile, comes across as a more outwardly jocular Ron Swanson, with flourishes of behavioral quirk rooted in Asperger’s Syndrome. (He confesses to eating the same thing for dinner every night for nearly 30 years, spaghetti with butter and white cheese sauce, until he became digestively unable to do so.)

For its first half hour, The Sunshine Makers seems like it’s going to play out as a wacky, Inventing America-esque history book version of The Odd Couple. And in fact a more dedicated hewing to that structure would have benefited the film. Mellen’s movie is at its best when using the two men, and both their personality differences and eventual divergence of opinion on their mission, as a prism through which to filter the philosophical question of whether drugs have a legitimate role in unlocking human brain development and hidden reservoirs of compassion. (At one point an interviewee notes, “Some people say, ‘I believe in God.’ I don’t have to believe in God. I have been one with God.”)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-