Time Isn’t After Talking Heads

In our latest Digital Cover Story, Paste takes a plunge with David Byrne, Jerry Harrison, Tina Weymouth, and Chris Frantz into the depths of Stop Making Sense 40 years later.

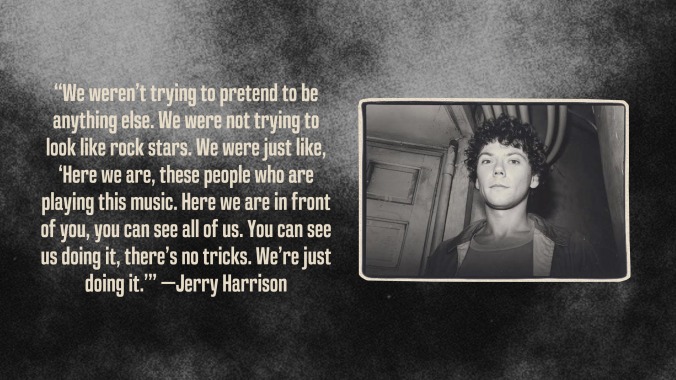

Photo courtesy of the artist

You know how this story goes. It begins with a pair of white tennis shoes walking on stage. Cheers from an audience begin to swell in volume, until one voice crawls through their noise: “Hi, I’ve got a tape I want to play.” Cut to a boombox and a click—a drum machine pulses, one of those tennis shoes begins tapping. Cut to a body—it’s David Byrne. Bug-eyed, clad in a gray suit and all alone, he begins playing “Psycho Killer” to a packed Pantages Theatre at Hollywood and Vine. He strums his way around the stage while the guts of his own backdrop are visible to anyone and everyone in the venue, even the very last row of the balcony. There’s a staircase to nowhere and some risers and ladders, debris scattered here and a few amplifiers placed there. When Byrne starts stumbling around, the boombox skips and glitches, as if a marionettist is controlling him from above. He breaks the fourth wall and looks right down the barrel of filmmaker Jonathan Demme’s camera.

The setlist fades gently into “Heaven,” and bassist Tina Weymouth joins Byrne onstage. Chris Frantz and Jerry Harrison are still M.I.A., but Weymouth isn’t alone. “I had David to watch and admire,” she says, “and I also had Lynn Mabry, who was waiting in the wings, singing the beautiful harmony along with David’s vocal. I was very happy.”

Before “Heaven” becomes “Thank You For Sending Me an Angel,” Frantz’s drum kit is wheeled out to center-stage. Byrne glances back at it while singing, “It’s hard to imagine that nothing at all could be so exciting, could be this much fun.” Donning his sore-thumb blue polo, Frantz counts them off and begins grinning from ear to ear, a smile that’ll stick around until the whole band takes a bow at the show’s end. Watch closely and you’ll notice that he and Weymouth don’t take their eyes off of Byrne for even a second. With the boombox that grounded “Psycho Killer” now gone, Frantz becomes the anchor, tasked with mirroring his playing from the previous three nights.

“He doesn’t play along to a click-track,” Weymouth continues, “but he wants a consistency, because he wants it to match up to the other nights that we recorded the song.” Harrison, who, like Mabry, was waiting in the wings, puts Frantz’s role into an even greater focus: “It’s one of the few places where he’s playing a featured role, like 16th notes, faster things,” he says. “And David’s playing 16th notes on the guitar, so it had that sense of being locked, playing very fast parts together—which wasn’t something that was that common in most of the songs we were playing.”

Together, the trio that formed Talking Heads from the ashes of the Artistics in 1975 deliver a feverish giddy-up of this nu-flamenco arthouse splendor. Byrne shakes, rattles and rolls; Weymouth and Frantz choogle precisely alongside him. It’s a scholarly compound of panicky, cowboy phantasma. “You can talk just like me,” Byrne yelps. No we can’t. The opening 10 minutes of Stop Making Sense are a crash-course on why Talking Heads are irreplicable. “Thank You For Sending Me an Angel” itself is a three-part, two-minute ditty that stands alone. No one else in the world can perform that song like that. “Our job is to be there and serve the song and serve the band and be support, because the frontperson has a lot of weight on their shoulders,” Weymouth says, “and when they know that the whole band is there and they’re all supporting one another and taking care of each other. It’s an awesome collaboration.” Byrne strums and vamps before boldly asking us to surrender to his demand: “But first, show me what you can do!”

And so the rest of Talking Heads shall.

I have been interviewing musicians for exactly the same number of years that passed between the release of Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues. After you do this gig long enough, you become less and less nervous each time you’re about to go on camera with somebody. But the jitters never fully leave you; you just stop noticing them so much. Two days before my scheduled Zoom with Talking Heads, I began to feel the anxiety of every interview I’ve ever done, times 10. Now an hour out from the call, my throat, chest and stomach are like butterfly colonies. I speak with my parents about it, telling them that I can’t even begin to emphasize what my life is going to be like 60 minutes from now—that this is the greatest American band of all time and my favorite band of all time; that I didn’t want to fuck it up. “Well, they’re not greater than Lynyrd Skynyrd,” my dad replies.

Talking Heads have not been available much these last 33 years. After an ugly breakup in 1991, Weymouth, Harrison and Frantz released an album without Byrne called No Talking, Just Head in 1996. In 2002, the quartet reunited to play four songs together at their Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. Frantz later lambasted Byrne’s creative supremacy in his memoir Remain in Love, while Weymouth once called him “a vampire.” (Byrne would concede that he was “more of a little tyrant.”)

Until September 11, 2023, the band hadn’t appeared in the same room together for 21 years. But, in a Spike Lee-hosted Q&A about A24’s upcoming 4K restoration and IMAX re-release of Stop Making Sense at the Toronto International Film Festival, Byrne, Weymouth, Harrison and Frantz stood together again. To the disappointment of many, they quickly dispelled any speculation of new music. Later, it was revealed that Talking Heads turned down $80 million to do a reunion tour, including a headlining slot at Coachella. Corralling them all onto my laptop screen together for an hour, in all honesty, felt like a miracle just as the TIFF appearance had months prior. For the first time in God knows how long, it appears that Talking Heads are happy to be in each other’s company once again.

Stop Making Sense was filmed across four shows at Pantages Theatre between December 13 and 16, 1983 (which is why Weymouth’s gray wardrobe loses sleeves between certain songs, why Byrne’s hair is slicked back out of nowhere on “Making Flippy Floppy,” and why Frantz’s polo changes colors). Talking Heads released their fifth studio album, Speaking in Tongues, that June after splitting up with producer Brian Eno, who’d worked on their three previous LPs. It went on to move enough units for a Platinum certification in the United States, a momentum built from lead single “Burning Down the House” reaching #9 on the Hot 100. The record was a goofy, captivating affair. Without Eno, the Talking Heads embraced self-production and followed their nonlinear muses, adopting elements of Black funk, gospel, opaque rhythms, slithering rock ‘n’ roll and commercially viable pop jitters. Three years earlier, Remain in Light sealed the band’s optimistic innovations in amber. Speaking in Tongues arrived acerbic in its own confusion. “As we get older and stop making sense,” became an embodiment for Byrne’s own spasmodic pretensions. It was all so madly splendid.

The four Pantages shows that make up Stop Making Sense concluded the North American leg of their Speaking in Tongues Tour, which saw the Talking Heads play 59 gigs between August and December of 1983. The run kicked off with a Late Night with David Letterman performance of “Burning Down the House” and “I Zimbra” before quickly turning full-steam ahead with a show at the Coliseum in Hampton, Virginia a month later. Stop Making Sense, rightfully lauded as one of the greatest documents of any band’s live talents ever, is the product of an ensemble having just spent four long, onerous months ironing out every single wrinkle in the setlist. Of course they were good; spend that long playing those songs and you’re bound to snap into place.

“By that point, we played a lot of these songs for quite a while,” Byrne laughs. “We were a band that played a lot live. We played a lot of live shows for some years before this, so I was locked into the groove from Chris and Tina, and then Jerry comes out and locks into the groove. [We wanted] to be as tight as we could possibly be.” Byrne pauses for a moment. “Not to brag about it,” he continues, “but when I listened to some of our really early live recordings, those are very tight.” “I’ve been really impressed with the [Live at WCOZ ‘77] recordings we made,” Harrison chimes in. “I was like, ‘Wow, boy, were we good!’”

When Harrison makes his entrance in Stop Making Sense, it’s during “Found a Job,” a track Talking Heads hadn’t yet pulled out of the bag on the Speaking in Tongues Tour. It replaced “Love → Building on Fire,” but the band doesn’t quite remember why the substitution was made—though Byrne quickly posits that it may have been at director Jonathan Demme’s request. “He could’ve been like, ‘Okay, this makes a really nice transition—a bridge between ‘Thank You For Sending Me an Angel’ and ‘Slippery People,’” he says. “I could imagine Jonathan going, ‘Oh, that would be a nice visual bridge.’” Demme, at the time, hadn’t put out a movie since Melvin and Howard in 1980, and he wasn’t yet the filmmaker we’ve come to remember him as—an Oscar-winning auteur responsible for Married to the Mob, The Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia in a five-year span. But Demme, ever the zealot with his finger on the pulse of the matrimony between music and storytelling, was the one guy in Hollywood who understood Talking Heads.

“He talked to us,” Weymouth says, “and he knew that we had a very unique point of view. And he loved that about us! And he loved music. You notice in all his films, music features very, very heavily. It’s not just a little background noise. The way that he spoke with us and interviewed us beforehand, to know what we were about and what we wanted and what we didn’t want, helped that communication even before we began. It helped enormously, to know what we were aiming for. We didn’t want a documentary type of film. We really wanted a concert. And he gave us that.”

One thing that sticks out with every viewing of Stop Making Sense is Demme’s choice to leave shots of the crew in the final cut. The band jams out during “Found a Job” while stagehands wheel risers into frame and set up amplifier cords. When Byrne, Mabry and Ednah Holt are harmonizing on “Slippery People,” there are shots of nameless workers checking their watches offstage just out of focus. Every motion—be it Harrison’s teardrop synth notes, Steve Scales’ taped fingers smacking a pair of bongos or Weymouth jerking her body to the rhythm of her own bass guitar—is an angle, a character, a piece of energy you can damn-near reach out and grab. The tempers of lighting, or the back of the stage being visible until Frantz’s drums obstruct it, or there being a very obvious no-drawn-curtains approach to exhibiting the concert’s assembly—it all feels intentional, and Broadway-esque.

Byrne has done plenty of work in that realm, having scored choreographer Twyla Tharp’s ballet The Catherine Wheel and written his own Broadway show, American Utopia, more than 30 years apart. When it came to building the story of the Speaking in Tongues Tour on stage, Byrne recalled going to avant-garde theatre productions in downtown New York in the 1970s. “I may have even worked with some of those people at that point,” he says. “But one of the things that I noticed was this transparency of showing the crew, and that it was okay to show them. Usually, their instruction is, ‘If you’re seen on stage, it’s a mistake and something’s gone wrong.’ That was a bit of a learning curve for [the Stop Making Sense crew], [understanding that] being on stage is not a mistake—that it’s okay to be on stage and we’re going to actually acknowledge you at the end, because people will have seen you as part of the show.”

It harkens back to Stop Making Sense’s beginning, when the show fills out piece-by-piece, character-by-character, until it’s nine people on stage in complete sync with each other and their engines of songcraft and unity are captured by eight cameras surrounding them. Everybody thinks about the geometrics of Byrne’s Big Suit, but there’s something to be said about how the Talking Heads approached the concert without any reservations about honesty. They wanted to show off the moving parts, the gears and the guts. Stop Making Sense, despite its title, makes perfect sense. It’s like a blueprint, or an instruction manual. There’s something formulaic and mechanical about the show and yet, it is all wonderfully beautiful from that first strum of “Psycho Killer.”

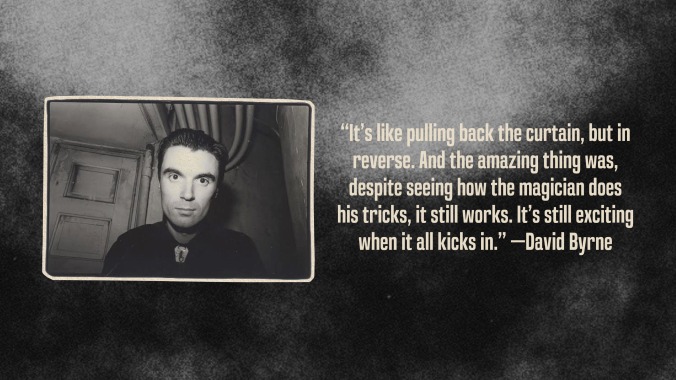

“It was an idea about transparency—let’s show the audience what goes into making the show. You’ll get to hear what each musician adds to the music and what they add as their personality, then you’ll see the crew come in. They’ll bring lights in and the risers. The projection screen goes down, you see everything that goes into it. It’s like pulling back the curtain, but in reverse,” Byrne says. “And the amazing thing was, despite seeing how the magician does his tricks, it still works. It’s still exciting when it all kicks in.”

That approach feels reminiscent of Talking Heads’ CBGB and Max’s Kansas City days—or, as Harrison puts it, the band’s “it’s dark, just turn on the white lights” era of performing and recording. The minimalism and the unified choreography, the color palette, the symmetry of how every member was stationed proportionally and the delivered-on-a-plate means of construction wraps up into this very strange and original and handsome pocket of stagecraft that isn’t melodramatic, but wholly truthful.

“From the very start, we didn’t want to feel cluttered. There was a kind of clarity that we aspired to. Even when parts got more complicated, we tried to make sure that you could hear them and feel them and see how they would interact with each other,” Harrison continues. “We weren’t trying to pretend to be anything else. We were not trying to look like rock stars. We were just like, ‘Here we are, these people who are playing this music. Here we are in front of you, you can see all of us. You can see us doing it, there’s no tricks. We’re just doing it.’ That continued into, I think, the ethos that, even though it’s far more complicated and more staged, became Stop Making Sense.”

Weymouth jumps in. “That’s because we all have, somewhere inside of us, something of a classical background,” she says. “With our arrangements and our music, we tried to write things that would compliment each other like a quartet or use ‘unison’ for emphasis or dynamics. But we were always very conscious of all of these tools in the musical kit, so we were very supportive of each other having different ideas. Sometimes it would seem very competitive, but it was good. Complacency is the worst thing to have happen in a band, so we liked that we had this platter of ideas and it was everybody trying to get them in but not clutter it up. That was important on stage, too.”

Stop Making Sense doesn’t succeed without Steve Scales, Lynn Mabry, Ednah Holt, Alex Weir and Bernie Worrell. Worrell had been a founding member of the Parliament-Funkadelic collective before joining Talking Heads in the early ‘80s, while Weir first came up as a guitarist in the Los Angeles funk band the Brothers Johnson in the 1970s before linking up with the New Yorkers. Weir, who worked with Harrison on his solo records, completely changes the music with his guitar playing—to the point where it’s difficult to even begin articulating why his imprint was so crucial. But when he runs in place side-by-side with Byrne during “Burning Down the House,” you just know it. Together, he and the other five players helped turn the Talking Heads into an ensemble, and ensemble casts were Demme’s preferred flavor at the time. “The stuff he did, like Citizens Band and Melvin and Howard, you get to know all these different characters and then you’d see how they interacted,” Byrne says. “And I thought, well, he just brought that to our show! You get to know each person as they come out, and then you see how they interact with one another. They can tell a story that way.”

Demme, who died in 2017, let his imagination become a tempest of narrative progression. From the bare stage to his unorthodox lighting choices (during “Girlfriend is Better,” a crew member uses a handheld light to make shadows in the background behind the band) to the candid close-ups of each player, the filmmaker’s choices were technically impressive and never too pretentious—always in service of the band and the music, never of his own selfish pursuits. In a 40-year career, Demme worked with some of the most popular movie stars ever—Jodie Foster, Tom Hanks, Anthony Hopkins, Michelle Pfieffer, Denzel Washington, Meryl Streep, Anne Hathaway—and David Byrne was one of them.

From his sinuous, tube man-like twists during “Life During Wartime” to the mad scientist getup of “Once in a Lifetime” to the introduction of him in his Big Suit during “Girlfriend is Better,” Byrne’s exaggerated onstage confections were their own one-man plays of choreographed, batty performance. Demme, like any director with a lick of sense, smartly put a camera in front of Byrne as he grew larger than life in the blink of an 88-minute concert. And, in every song, we watch the rest of the band speak in a language of looks and movements, encouraging each other with not their words, but with their playing. They felt every second and every note of these songs. Because of that language, we feel all of them, too. When Weir looks back at Worrell during an instrumental passage in “This Must Be the Place,” you’re convinced the entire world outside of the Pantages Theatre came to a stop.

“[Editor] Lisa Day and Jonathan, they were looking to get all those little details into the film, so that you would see what they were doing,” Weymouth says. “There’s a communication between Bernie and Jerry, [they’re] challenging each other. And then that’s also going on between David and Alex on guitar. It’s just a beautiful thing to watch it and to notice it.” Harrison echoes his bandmate’s awe. “I find that, every time I watch it, I’ll notice a glance or a recognition of something between people,” he says. “Sometimes it’s as far away as Bernie to Alex that is caught in a fraction of a second. Seeing it over and over again, you start to almost look for the things you haven’t seen. It’s been wonderful to go, ‘Oh, wow, that was caught? That’s so cool, that little glance or those communications.’ I think that Jonathan was well-aware of the fact that there were these little stories going on in those communications all throughout the set, and he was trying to acknowledge them and capture them.”

Because Demme was stuck filming Swing Shift in the afternoons, he brought in Sandy McLeod as a visual consultant for Stop Making Sense and enlisted her in mapping out the shot sequences for the performance. She toured with the band for three months, taking notes on each song and tooling camera placements. “It was really beautiful that we had these wonderful, amazing people working on the film with us,” Weymouth says, “because they knew how to just capture these really beautiful little intimate moments. And yet, it would become such a public statement. When they’re all singing and their mouths are open, it’s just so beautiful, with the lighting on them and on David. It would be a cartoon, except it’s just very human and moving and sensitive—these things I would never think to say, ‘Oh, go look at that!’ That had to be picked up by somebody who was there, watching us.”

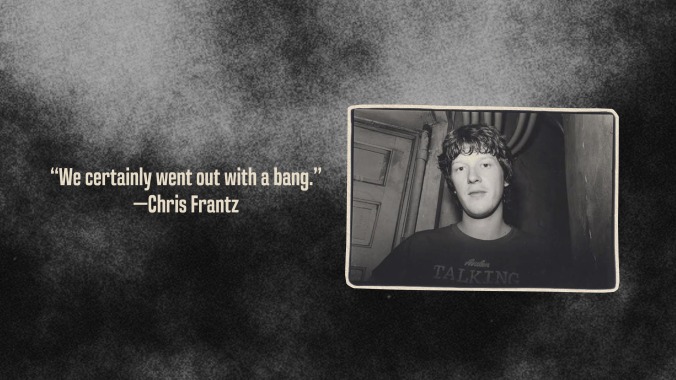

When Talking Heads began the Speaking in Tongues Tour, “Burning Down the House” had not yet cracked the Top 10 on the Hot 100. Knowing what we know now, and that the song was a hit by the time the Pantages shows happened, it might seem peculiar that the band opted to place it seventh on the setlist. But what doesn’t get shown in Stop Making Sense is that they were doing it as an encore, too. “In the old days of early rock ‘n’ roll, people would do that. They would have a hit song and they would play it once, it would get a lot of applause and then they’d play a few more songs and then come back with it again at the end of their show,” Frantz says. “They’d go out with a bang. We certainly went out with a bang.” Byrne remembers how, as the tour progressed, the audience seemed to know the words to “Burning in the House” more and more as the song received continued radio play. “The audience would get a bigger and bigger reaction from that song, but it was still stuck in the place where it was [in the setlist],” he notes. “It worked, we were gonna leave it there.”

The most unforgettable sequence in Stop Making Sense happens when Talking Heads play “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody)” and “Once in a Lifetime” back to back. If I had been at one of the Pantages shows, that would’ve been a dangerous cocktail of tracks to sit with (the guitar-playing from Weir at the beginning itself is a treasure trove)—it’s a checkpoint in the show that’s as crucial and momentous as the finale sequence of “Girlfriend is Better,” “Take Me to the River” and “Crosseyed and Painless.” While “This Must Be the Place” is one of the greatest love songs ever penned (“And you’re standing here beside me, I love the passing of time” remains one of the sweetest proclamations of comfort in all of rock ‘n’ roll), “Once in a Lifetime” is, as Harrison succinctly puts it, “a special song” that doesn’t come in with a bang like “Burning Down the House.” Instead, he says, it flows in.

“It’s like a wave washing in on you,” Harrison adds. “You have to find a special place for it in that way.” The choice to pair those songs together was done for practical reasons, too: “Sometimes, it just had to do with not wanting to repeat songs that were in the same key,” Weymouth admits. “All those musical neurons don’t get bored, they get stimulated. You’re changing keys when you can, you’re wanting to keep the brain active and stimulated not just for the players, but for the audience.”

Both “This Must Be the Place” and “Once in a Lifetime” linger on domesticity and the idea of “home” in various forms, as if the former’s “Home is where I want to be, but I guess I’m already there” couplet feels like a spiritual continuance of the latter’s “And you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife” line. It’s a revelation: I could be anywhere, but I am here—a feeling likely shared by many in attendance, especially the men near the front row wearing college sweatshirts or sleeveless Talking Heads tour shirts. Both songs are like the musical personification of a smile emoticon, as well as harbingers of ordinary affections transcribed into beautiful disco ostinatos. Famously, Byrne sings “This Must Be the Place” while dancing with a floor lamp, an image that has inspired tattoos, welcome mats, home knick-knacks and endless social media captions for cute couple pictures. But that lamp endures as one of the most important props in music history, and a formidable waltz partner.

“We were using all these different lighting instruments—every kind of lighting instrument you could use just using regular white light—and one of them, one kind of lighting instrument that we’re all used to, is a floor lamp like we have in our house,” Byrne explains. “I thought, ‘Can we use that for one of the songs?’ And, of course, that song—where the word ‘home’ features over and over again—seemed like the perfect place to have some sort of symbol of domesticity, like a floor lamp. It makes it like, ‘Oh, we’re all standing around in a living room singing.’ Eventually, there’s that whole instrumental passage, and I thought, ‘I think I have to do something here. I have to do something. I can’t just stand here, as nice as it is.’ So I thought, ‘I’ll dance with the lamp!’” Frantz chimes in, avowing that Byrne “also managed to avoid putting the lampshade on his head.” “It might have been tempting,” Byrne laughs, “but I was also really concerned about breaking the lamp—because that did happen a few times, where it would slip out of my grasp, fall over and the light bulbs would break.”

Stop Making Sense quickly shifts after “Once in a Lifetime.” Byrne exits the stage, leaving the remaining eight members as the Tom Tom Club, Weymouth and Frantz’s husband-and-wife side project they’d started together in 1981. Jimmy Rizzi’s cartoon-like drawings, which adorn the covers of most of the Tom Tom Club’s album, are projected by “slide wrangler” John Chimples (he was also responsible for putting slides like “Star Wars,” “Onions” and “Dustballs” behind the Talking Heads during “Making Flippy Floppy”) and emphasize how the band wanted Rizzi’s artwork “to look like we’ve thought about our band, that we were trying things on like little kids making LEGO buildings,” according to Weymouth. “Jimmy could never draw a face in three-quarter view,” she adds. “It had to be frontal or side.”

The Tom Tom Club—which were, really, just Talking Heads minus David Byrne in this iteration—nose-dive into the rambunctious, post-disco jaunt “Genius of Love,” the Top 40 hit that has since been sampled by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five and, most famously, on Mariah Carey’s #1 hit “Fantasy.” Despite it being a freakish, jubilant, blinking detour after “Once in a Lifetime,” “Genius of Love” was never supposed to be in the final cut of the film, Weymouth says. Demme assured her it wouldn’t be there, too, but it wound up a transition between the two most memorable sequences of the flick. “It was there to entertain the audience so that David could go change into his Big Suit,” she continues. “We never had the intention of keeping it in the film. But, of course, it did end up there and it became a little bit of a, as the British say, con-trah-versy.”

Film critic Pauline Kael didn’t like it (she would later retract her criticisms in a re-review of the concert), and Weymouth admits that implementing those jarring strobe lights was her idea, as a means of camouflaging her “crab walk” dance moves. “I thought I needed this strobe to break up my dancing, because it was so awkward. It’s quite a cliché, and the Talking Heads were never supposed to be a cliché,” she says. “I should have just given [my bass] up to Jerry or to Bernie on keyboards. They could have done something really interesting, and then I would have danced around.” I jump in and tell Weymouth that the “Genius of Love” passage is one of my favorites in the film, and Harrison comments on how, in the original presentation of Stop Making Sense, the Tom Tom Club section had a “brighter feeling” than most of the songs that were near it. “It stuck out,” he says. “In the new scan, it’s a little more consistent in the way that the color looks. It flows through in a beautiful way.”

Weymouth, Holt and Mabry all sing in unison, the latter two replacing the former’s sisters Laura and Lani. Their three-part delivery of “I’m in heaven with my boyfriend, my laughing boyfriend” still echoes off the walls. And then there’s Frantz on the kit, spitting ad-libs into the mic like an emcee. “James Brown!” probably lingers in your ears after every listen, though Frantz remains bashful about it 40 years on. “Sometimes I kind of cringe when I watch it. But, what can I say, I had one shot,” he laughs.

“In a weird, odd, jolting way, that herky-jerkiness refers back to how we started as a group,” Weymouth adds. “When it was just a trio, even before Jerry joined, for two years we were just kids with a cartoon, toy-box sound that we were trying to put together. We were definitely not trying to be what other bands were, and we thought this was the way we were going to find out who we were. The good thing about [‘Genius of Love’] was that it ended up, over time, becoming something that worked—because everybody knows, ‘Oh! It’s those people. Those people, they’re connected.’ That was a plus. You know what they say: One hand washes the other, and the little Tom Tom Club was trying to help the Talking Heads, because we loved our bands. We loved both of them.” After a funkified breakdown jam, Frantz tells the audience: “Nice to be here, we gotta change back into the Talking Heads.”

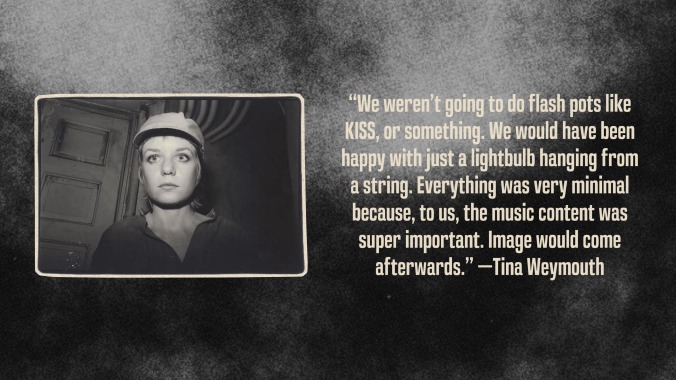

And when the lineup does change back to Talking Heads, the pinnacle of concert film theatricality presents itself: Byrne returns to the stage in his Big Suit, which he created to fuel his interests in symmetry and geometric shapes. The goal was to make his head look smaller. “The easiest way to do that was to make my body bigger,” he said in a promotional video 40 years ago. The band rips into a colossal rendition of “Girlfriend is Better,” and the five-minute performance has since become synonymous with the imagery around the entire film. But It all feels like an entirely different world from when the Talking Heads were just a trio playing at CBGBs with bare lights and no gels. “We weren’t going to do flash pots like KISS, or something. We would have been happy with just a lightbulb hanging from a string,” Weymouth says. “Everything was very minimal because, to us, the music content was super important. Image would come afterwards.” Talking Heads’ image didn’t really take off until the art of the music video opened up the floodgates for pop music. Byrne was especially taken by the camera, studying and observing it whenever he could (a fascination that would lead to his film True Stories in 1986).

“It worked really well afterwards to be a little bit weird and not what you expect,” Weymouth continues. “And our music, we did the same thing with our music. We would tug it all apart. Some of our parts would be very jocular and kind of jokey while David would be singing something extremely serious. And then we would juxtapose it in other ways, to just completely take the piss out of something. We would change things emotionally, using the music, and we were doing it willingly. It really was part of the design, because that was how we were. I didn’t go to music school, none of us did. We did go to art school and architecture school, so we understood something about structure.”

None of Talking Heads’ eight studio albums sound alike, and that was entirely the point—the variety, a product of the band wanting to try new ways of recording each time they hit the studio, is part of what makes Stop Making Sense so bombastic and primitive. You can tap in at any point and get lost in the juice. “We had our own force ahead of us,” Harrison says. “The first album, we had chosen Tony Bongiovi to be the producer—a choice very different from other bands coming out of CBGBs—and then we met Eno and said, ‘Oh, let’s go to the Bahamas [to make More Songs About Buildings and Food].’ [With Fear of Music], we said, ‘Well, we really feel more comfortable where we rehearse than we do when we go into another studio. It’s a whole new room, it doesn’t sound the same to us. Why don’t we just record it here?’ We recorded on a couple of Sundays, because that’s when the traffic was quietest in Long Island City, where we rehearsed. There was this attempt, by using the process of how we went about making the album, to push us and force us into new ideas and new ways of thinking. I think that we continued that all the way through.”

Talking Heads never felt any pressure to copy Bowie or anybody else, for that matter. They were influenced by African music, but there was no inclination to match what was popular on the radio. Their most commercial hits (“Burning Down the House” and “Wild Wild Life”) sounded immune to contemporary comparison, too. An album like Remain in Light sounds like four people having separate conversations in the same room and, by the sheer grace of some cosmic coincidence, their topics overlap eight times. Talking Heads were art school contrarians—stewards of their own nonconformist convictions. “That’s why I joined your band, guys! Because you weren’t like everybody else!” Weymouth yells at her bandmates with a laugh.

Even when Talking Heads covered songs, like the penultimate Stop Making Sense track “Take Me to the River,” their takes arrived from a completely different planet than any of the source material had. “When we started performing ‘Take Me to the River,’ I thought, ‘Oh, wow, we sound like Al Green now!’ I did, I really did. ‘Oh, the drums sound just like on the Al Green record,’” Frantz says. “Well, of course, we didn’t sound anything like that, and that’s what made it so good. It’s a whole different perspective, audio-wise.” Harrison, who would play with Teenie, Leroy and Charles Hodges years later, admits that he never went and listened to Green’s original recording until many years after Talking Heads covered it. “I never tried to copy what the Revered Charles Hodges was doing,” he laughs. “I just played the chords that David had just shown me. Levon Helm, Bryan Ferry and Foghat had all these versions of ‘Take Me to the River’ come out almost exactly at the same time we did. Unfortunately, ours is the one that caught on.”

The encore performance of “Crosseyed and Painless” was one for the books. Everyone on stage is drenched in sweat, and Byrne’s shirt—now untucked—is completely soaked through. Weir blisters through a searing, angular riff, while Harrison and Worrell make eye contact with each other and crack grins. There’s a brief moment where, as the song is barreling toward a rest, Byrne places his hand on Weir’s guitar himself. The audience is featured heavily in shots; they’re a part of this now, too. A young child holds a stuffed unicorn up at the band, the cameramen are shown bobbing their heads to the “I’m still waiting” breakdown, each player gets a romantic final close-up, and the crew is formally introduced before the final curtain closes. Byrne bids Los Angeles goodnight and exits stage left. It’s like a taste of medicine.

So what happened next? “We probably had a drink and then went to the hotel pool,” Byrne laughs. It was business as usual, though it would be the last concert the four played together in the United States as Talking Heads (they would appear together at a Tom Tom Club show at the Ritz in New York City in 1989, performing “Psycho Killer” with Weymouth singing lead). Gone were the stresses of having to book it to Milan from Berlin by bus last-minute because Italy’s air traffic control organization went on strike, or the band’s “the more we did, the more we had to do” attitude from their Downtown Manhattan days. Stop Making Sense, in many bittersweet ways, is the touted and perfect epilogue to the Talking Heads we knew best. They’re still romantic about the early moments. “I remember when we could play a weekend at CBGBs and fill the place for a whole weekend,” Byrne says. “I remember that’s when we knew we could definitely quit our day jobs, because the rent was really low. We were making enough money from playing even just clubs.” Before Talking Heads became Talking Heads, they were on weekday bills opening for Blondie and the Ramones to empty rooms in the East Village.

“There was a brilliance to the design of CBGBs,” Harrison adds. “It was a long, narrow room with the stage at one end. Because it’s narrow, it doesn’t take that many people to be upfront at CBGBs for you to feel like you really have an audience. It’s not like when you go into a theater that’s wide and vast and, if you’ve sold out half the tickets, you’re so aware of the empty seats. At CBGBs, you were looking through people. It meant that, if multiple bands were playing, [when] the bands that you were less excited [were playing], you’d go to the back of the room but you probably would have a conversation and it would even spill out onto the sidewalk. It was almost perfectly designed for up and coming bands to experiment and build an audience. We got to the point that everyone was there to see us and you could feel that all the way back. But the front was still very narrow. Those were the people that had taken the time to push their way up there.”

But even back then, when Byrne, Harrison, Weymouth and Frantz were making records like More Songs About Buildings and Food and Fear of Music, they knew their music was going to last. “That was the whole point, it was, ‘Hey, let’s make something that we can be proud of 50 years from now,’” Weymouth says. “That’s the historical bookmark that people put in: ‘Will it stand the test of time 50 years down the road?’ And I think it will, especially because we have so many offspring. We have so many children.” Weymouth is talking about the Vampire Weekends and the St. Vincents of the world, or the 16 musicians featured in the recent Everyone’s Getting Involved tribute album, like the National, Paramore and Lorde. “Those kids are our kids,” she furthers. “Even though we didn’t birth them and we don’t know them, they grew up listening to and feeling our music. Had we just been playing rock, 12-bar blues or something like that—and we have total respect for that genre, it’s a great American invention—but would they notice us the same way? No.”

Some say the only flaw of Stop Making Sense is that, after “Crosseyed and Painless,” it ends. When Talking Heads reunited in Toronto last autumn, discourse online quickly unraveled into one question: Would them playing music together again disrupt the legacy they’ve left so perfectly in place for 33 years? Many of us are content with the closure Stop Making Sense provides. It wasn’t a coda to one of the best six-year runs in music history, but an exclamation point on a cherished chapter of an everlasting lexicon of performance—even if they released three more albums after. If you saw the clips of IMAX theater audiences across the country getting up and dancing during screenings of the film last year, it’s obvious that Talking Heads’ music still has stories to tell and people to meet. It’s one of the greatest love stories ever captured on 35mm.

Before Stop Making Sense, though, the band had already turned in one of the greatest live shows of all time when they played the Palazzo dello Sport in Rome on December 17, 1980 (a concert whose energy was vaulted into the stratosphere by the piercingly one-of-a-kind, twistedly tone-setting guitar work from Adrian Belew and the kinetic madness of a then-28-year-old Byrne). “It was our pleasure to get the audience revved up,” Weymouth boasts. I’d say it was a pretty good run for a couple of Rhode Island School of Design dropouts and a Modern Lovers expat who found each other in a lifetime we all exist in, too. And still, even after all that singing and dancing, you can hear one final voice yell out “Encore!” as Talking Heads exit the Pantages stage for good.

Matt Mitchell is Paste’s music editor, reporting from their home in Northeast Ohio.