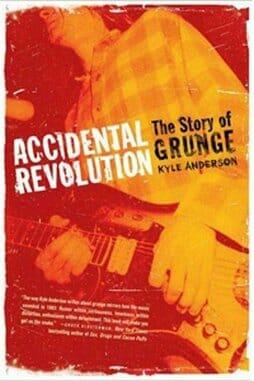

Kyle Anderson

Strum As You Are: How the flannel brigade saved and killed rock in one fell stroke

And so in 2007 I find myself thinking about the genre known as “grunge” more than any sane person rightly should. Popularized by Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains and, of course, Nirvana, grunge was based entirely on alienation, nostalgia and loud/soft dynamics. It was joyless, self-righteous and predicated against a demonized mainstream. As a teenager, I sucked the stuff up; revisiting it now feels like stumbling over a yearbook picture of myself with zits and a rat-tail.

Kyle Anderson, an editor at Spin, knows the feeling. As someone who cares enough about grunge to write a book about it, even he acknowledges that grunge has not aged well, and so instead of trying to redeem the genre, his book wisely sticks to chronicling its history and examining its cultural significance.

If rock ’n’ roll is a genre for the people, it was hard to tell in the late ’80s, when the airwaves were ruled by plasticized hair metal so divorced from the average rock fan’s reality that it seemed more fantastical than any Lord of the Rings fantasy Led Zep could have cooked up. Like any gilded Babylon, hair metal’s foil would have to be its opposite: something dark, messy and utterly average.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-