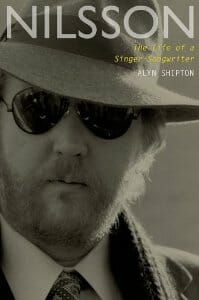

Nilsson: The Life Of A Singer-Songwriter by Alyn Shipton

He put the lime in the coconut

Harry Nilsson’s story can be adjusted to fit any number of narratives. He’s the poor kid who made good but couldn’t handle success. The hard-working banker who wrote songs all night. The wacky artist. The Beatles fan who tried to drink his idols under the table. One of a crop of artists in the ‘60s and ‘70s who helped redefine the power of the studio in pop music. A symbol of the crazy excesses of the recording industry in the old days.

Alyn Shipton’s biography of Nilsson (the first) shows in meticulous detail the ways these stories come together to capture a man described both with superlatives—“finest white male singer on the planet”—and caveats— “nobody…is as much of a paradox.”

Biographies about musicians from the ‘60s and ‘70s can often be reduced to a sort of checklist:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-