Eighth Century Chinese Writer Tu Fu Is The Greatest Poet You’ve Never Heard Of

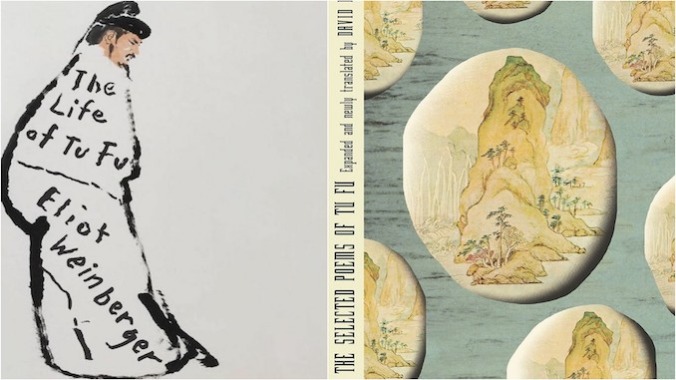

Photo: New Directions Publishing

Of all the greatest poets that have ever written, which is the least known to American readers? I would join many others who point to Tu Fu (a.k.a. Du Fu). He wrote 16 centuries ago during the Tang Dynasty, a golden era of Chinese painting, calligraphy, and poetry. Those artists were able to transform the spiritual ideals of Taoism and Buddhism into incredibly intense engagements with nature and ordinary people. Many excelled, but none did it better than Tu Fu.

The American poet/essayist Eliot Weinberger has just published The Life of Tu Fu, a book too eccentric to make the Chinese poet famous in the West, but that is nonetheless resonant with what makes him worth knowing. Weinberger has penned not a standard biography nor a critical study but rather an extended poem that borrows fragments from Tu Fu’s writing and extends them into an impressionistic consideration of his work and life.

In the second section of his book, for example, Weinberger writes:

In the Eastern Capital it is tiring being clever.

Chanting poems in the Hall of Gathering Kingfisher

Feathers, drinking in the Pavilion for Gazing at Clouds.

They only talk about plum blossoms and never notice

the new shoots of a willow.

The Tang Court’s Eastern Capital was Chang’an, now known as Xi’an. From 705 to 755, it enjoyed half a century of relative peace and prosperity, which allowed its poets and painters to depict a world in harmony with itself.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-