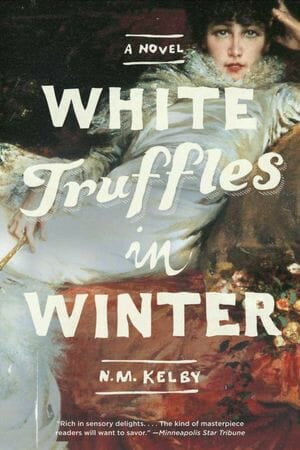

White Truffles in Winter by N.M. Kelby

Love in the Time of Colanders

White Truffles in Winter, an unusual, well-seasoned stock of memoir, love story, essay and historical romance, deliciously simmers along, tempting a reader to tear out the pages and eat them as they move through this tasty novel.

Kelby deliciously blends high concept and haute cuisine in a novel exploring the life and loves of Auguste Escoffier, the legendary French chef who started the famous kitchens at The Savoy and The Ritz and perfected the workings of the modern restaurant kitchen. Without Escoffier, we’d have no Paul Bocuse (nouvelle cuisine), no Alice Waters (seasonal organics), no Marco Pierre White (rock ‘n roll in recipe). We’d also live in a world bereft of The Peach Melba, Cherries Jubilee, or Fraises a la Bernhardt.

If you note that these signature dishes created by Escoffier all bear the names of women, you’re on to the general conceit of White Truffles.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-