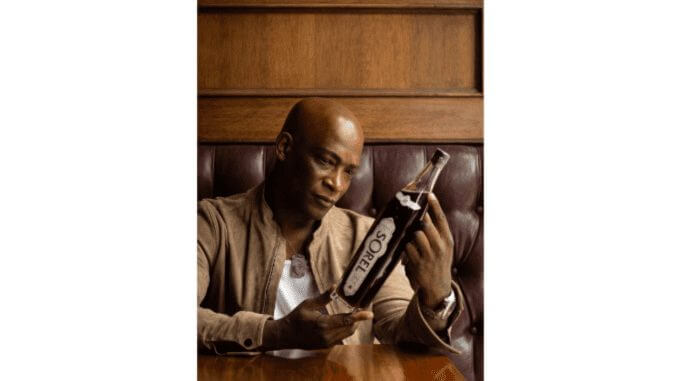

The Spirits Producers Reclaiming and Honoring the Terroir and Culture Colonialism Captured

Photo by Fred Crandon/Unsplash

The legacy of colonialism continues to define business today, from fast fashion to farming to spirits.

While many individuals and organizations are beginning to denounce overt examples of cultural appropriation and serious debates around reparations for descendants of enslaved people in the U.S., the UK and elsewhere are finally gaining some traction in the halls of power, many of the products we consume regularly—from your favorite dish at your local takeout joint to spirits—are arguably products of a culture’s plunder and conquest.

And too often, the process, even today, of creating those almost universally beloved delights are done in such a way that injury after injury—economically, socially, culturally—is added to the original foundational insult of colonialism writ large.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-