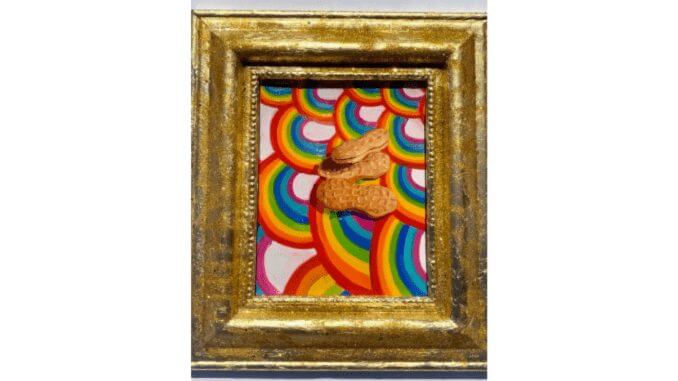

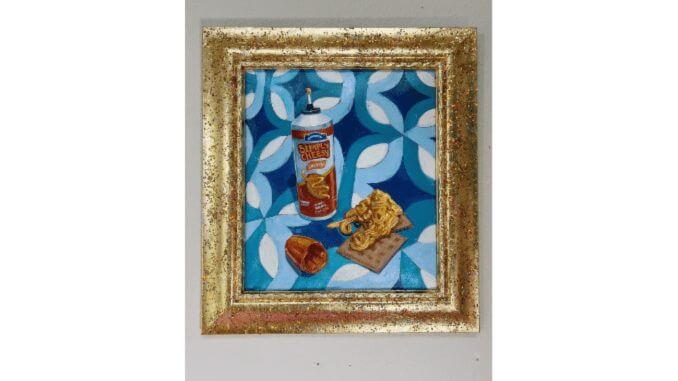

An Interview with Sari Shryack of Not Sorry Art on Her Gilded ‘Junk Food’ Series

Artwork by Sari Shryack

I spoke with painter Sari Shryack of Not Sorry Art about her gilded “junk food” series. In this series, the Austin-based artist places her paintings of iconic “junk foods” from the ‘90s and early 2000s, from Cosmic Brownies to Cheetos to Mountain Dew, against colorful patterned backdrops set in sparkling gold frames. The pieces draw on her and her loved ones’ experiences with food as they grew up below the poverty line and ask us to view foods commonly associated with poverty in a new light. This series requires us to confront our conceptions of how food and class are intertwined in our culture, simultaneously stoking a sense of relatable millennial nostalgia.

As the wealth gap continues to grow, work like Shryack’s becomes increasingly salient. We as a culture must question our own deeply entrenched classism to imagine a better, more just world, and thinking about food is a great place to start. Here’s how my conversation with Shryack went.

Samantha: Can you tell me a bit about your background as an artist?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-