Silent Hill 2 Remake Is Good, But It’s Missing What Made The Original Special: Camp

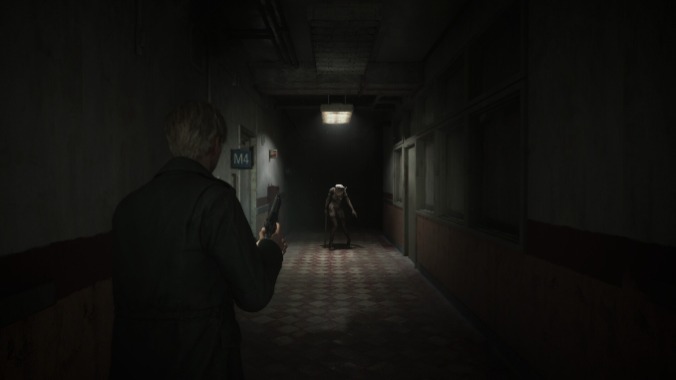

There was CAMP here. It’s gone now.

It’s a bit of an understatement to say that the Silent Hill 2 remake came with heaps of baggage. For starters, the series has been a flailing mess since Konami allegedly made the short-sighted decision to dismantle Team Silent, the legendary studio that made the initial four Silent Hill games, and after a string of largely derided entries, there was tremendous pressure on this first major release in over ten years to land. On top of this, many were concerned (or, in some cases, flat-out dismayed) that Bloober Team was handling development, whose output, like The Medium, has ranged from divisive to hated. Oh, and then there’s the little detail that it would be attempting to remake what’s considered by many (myself included) to be one of the greatest horror games ever made, a work that is singular, strange, and so of its time that it seemed impossible to recapture what made it stand alone.

And then the game came out, and everyone seemed to like it. Or most people, anyway. Early reviews lapped on praise, and so far, audiences seem to be enjoying it too, as it quickly hit the sought-after “Overwhelmingly Positive” user review threshold on Steam. Sure, there have been a few common criticisms, like its poorer pacing than its predecessor. The original is roughly ten hours long, while this sequel took me around 18 to get through, and much of that added time felt less like it was elevating the storytelling and more like it was spent bashing far too many jittering abominations with an iron pipe. While these scuffles were more “polished” and “fair” than those in the original—in large part because you can do a Bloodborne-style invincible step-dash—there’s still way too much spent shooting monsters in the head.

However, outside of these complaints, there’s a lot to love. The sound design is similarly creaky and gnashing, as inexplicable audio cues meld with diegetic gurgles, squelches, and the crackle of your radio. As these nightmare noises fill your ears, you’ll journey through a rust-colored hell realized with an uncomfortable degree of detail. These more expansive, in-depth backdrops set the stage for a brand of non-stop intensity that lands like blunt-force trauma.

And perhaps one of the most noticeable differences is that much of the voice acting is excellent. In particular, Luke Roberts’ performance as James is affecting and deeply human (perhaps to a fault, considering some of the story’s themes), which, when combined with the emotive facial animation, makes it clear that this version of the character is the saddest most pathetic man who’s ever lived. His scenes are bolstered by some sharp editing and cinematography, which help the game stand out compared to many other AAA titles with less defined aesthetic identities. And most importantly, the scares still land. Pyramid Head remains terrifying, and all is right with the world.

However, even though this remake largely succeeds in its aims, at least for me, I slowly began to feel something was a bit off, as if too many rough edges were sanded down. After all, the original stands out because of its many idiosyncrasies and weird details, some of which have been paved over in pursuit of “modernizing” the experience—the fixed-camera angles, the lo-fi pixelated graphics, tank controls, and numerous other old-school frictions that created unique textures. But of these discarded elements, there’s one that I particularly miss, a gaping hole at the center of this experience: the remake is missing camp.

Silent Hill 2 is defined by layers of metaphor, mastery of atmosphere, its one-of-a-kind soundtrack, striking imagery, an unparalleled ability to instill fear, compelling ideas, and other superlatives. If you were to describe its vibe, you’d likely begin with its undeniably oppressive ambiance, a glimpse into a tortured man’s psyche. However, what these descriptions fail to acknowledge is that it’s also frequently silly. Like, very silly. The most obvious examples come in the cutscenes, specifically via the English-language vocal performances, which are almost entirely delivered in a heightened, wilting affectation that makes everyone sound confused, lost, and wooden. James, in particular, says nearly everything with this alienating, awkward cadence that, at least up front, feels intensely at odds with the otherwise self-serious atmosphere.

Of course, a classic example of this is the scene in Pete’s Bowl-O-Rama. After James endures countless horrors, he stumbles upon Laura and Eddie hanging out as the latter bites into a tasty pizza that has materialized in this living purgatory. After a brief exchange, Laura, who is a small child, runs away. Affronted by Eddie’s refusal to help him find her, our protagonist stammers out, “This town is FULL of monsters. How can you just sit there eating PIZZA?” Another favorite is later when James emphatically says to Eddie, who now has a gun, “Eddie, you can’t just kill someone because of the way they looked at you,” and Eddie goofily responds, “Oh yeah? Why not?” In a word, these scenes are camp.

Before I go further, though, it’s worth digging into what the word camp actually means. While the term has a long history, writer and critic Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp’” is frequently cited as helping bring attention to this sensibility that was frequently championed by queer culture. Structured more as a series of “jottings,” as she puts it, she outlines 58 observations about camp, which she defines as “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration” and that “it is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.”

Essentially, camp is when something “fails” or is intentionally styled to “fail” but does so in such a vigorous and over-the-top way that in its artifice, earnestness, and style, it still comes across as endearing. There’s naive or pure camp, which is when this failure is a happy accident. Then there’s “camping,” which is when this effect is created intentionally, which Sontag argues usually doesn’t work due to coming from a place of contemptuous self-parody. When this form does land, though, she says it’s because it “reeks of self-love” instead of judgment. Perhaps most essentially, “people who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as ‘a camp,’ they’re enjoying it,” and they think “it’s good because it’s awful.”

To be clear, I’m not saying that Silent Hill 2 is awful, but that judged by most standards, the voice acting and much of the dialogue in the cutscenes are the definition of “exaggerated” and “off,” as Sontag puts it. I don’t know if this stilted energy is accidental naive camp or if it’s intentional in the same way that Naomi Watts’ performance in Mulholland Drive is deliberately overdubbed, but in either case, it evokes a similar sense of surreality.

However, what’s most interesting about Silent Hill 2’s camp isn’t just that these scenes are amusing on their own, but the contrast between these elements and the game’s larger tragic and often grotesque imagery. You’ll fight for your life in dingy hallways and decrepit prison cells as skin-crawling sounds croak from the pitch-black outside the beam of your flashlight. The camera frames these horrible locales in a way that accentuates this discomfort, and many of the most haunting moments aren’t from when you’re battling spasming creatures that reference the monstrosities of Jacob’s Ladder, but in the spaces between these moments of violence, like when you see your tormentor from the first time, silently staring from behind prison bars. It all builds, culminating in awful truths that creep out of the dark like a knife-wielding monster. And then, after all that, you go into a cutscene where James talks about pizza. It’s in this contrast between camp and deadly self-seriousness that the game works its magic, dizzily bouncing back and forth between modes as it pulls us into a warped vision that defies traditional aesthetics, a form of tonal whiplash like no other.

As for how this bizarre incongruity ties into Sontag’s description of camp, she outlines three “great creative sensibilities” that are successful modes of art. The first is “the pantheon of high culture; truth, beauty, and seriousness,” meaning things traditionally classified as “high art,” and she cites The Iliad, Rembrandt’s paintings, or Beethoven’s quartets as examples. Then there’s a second, more grim style, “the kind of seriousness whose trademark is anguish, cruelty, and derangement,” like Sade, Kafka, or Hieronymus Bosch, a space where horror often resides. The third is camp, which skirts around this seriousness entirely. Considering what we label as camp now, a few of her examples of this sensibility may surprise you. Sure, she mentions King Kong (1932) and Flash Gordon comics, but also Swan Lake, some of Mozart’s pieces, and Art Noveau because rather than being exclusively associated with any particular genre or form, any work can be camp if it meets the previously defined criteria.

While Silent Hill 2 would most traditionally be placed in the second category thanks to its corroded hells that would make Bosch blush, it also liberally borrows from the third. However, mixing these two isn’t necessarily how it’s supposed to work, at least according to Sontag. She says, “Camp and tragedy are antitheses” and that the “whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious.” But despite this, here we oscillate between serious and not, jerking back and forth as it delicately balances both in its cutscenes and elsewhere. Perhaps much of this contrast works because, unlike most other mediums, games jump between decidedly different modes as you go from non-interactive sections to interactive ones, but even here, things aren’t so straightforward.

Because while this world is presented by carefully placed fixed camera angles which help create claustrophobia and draw the eye towards things we don’t want to see, the weighty tank controls lead us to bump into furniture and walls as James stumbles through these ornately arranged frames like a bumbling buffoon. Even if you have the tank controls turned off, combat is still inelegant, and you’ll be gashed and slashed while our protagonist tries to bonk a writhing abomination with a 2×4, something that frequently leads to moments of unintentional comedy as you screw up royally.

While I’m sure these contrasts were felt somewhat when the game came out, they’ve only become more apparent with time. The game’s horror, recurring symbolism, and sound design hold up perfectly, but its mechanics clash with modern sensibilities. However, while this makes it sound like its old-school gameplay is irredeemably flawed, at least for me, this isn’t the case. Survival horror games working in this pre-Resident Evil 4 paradigm have their own appeal, and the disempowering, spastic fights have a charm of their own. “Many of the objects prized by Camp taste are old-fashioned, out-of-date, démodé,” Sontag says. “What was banal, can, with the passage of time, become fantastic.” Silent Hill 2 is more than 20 years old, which is a very long time in the relatively brief lifespan of videogames, and the “old-fashioned” oddities of its mechanics further lend an air of camp.

Hell, even elements like the back-of-box text, with its wonky font and out-of-fashion vernacular, read as camp: “THE SILENCE IS BROKEN…” it ominously states. Perhaps most succinctly, the banger introductory music video, which plays when you start the game for the first time, acts as a perfect shorthand for what the game is doing. This sequence foreshadows the narrative and themes as “Theme of Laura” delivers stirring acoustics, which intermingle with painfully earnest line deliveries from James, the entire thing tinged with an intensely early aughts MTV vibe. It all combines to make this intensely specific flavor, as camp and a well-curated sensibility of “anguish, cruelty, and derangement” create a one-of-a-kind panache.

Somewhat predictably, the Silent Hill 2 remake ditches much of this oddball energy. As previously mentioned, its cutscenes are polished, featuring emotive performances, detailed facial animation, and pristine camera work that deliver a consistent stream of solemnity. The pristine, photorealistic detail of these environments comes together with unrelentingly brutal sequences that are sometimes downright mean—there’s a new breed of mannequin monster that skitters in shadows and along walls before suddenly doing a jump-scare by punching James in his deeply sad face. Much of the game’s additional length is dumped into its most oppressive areas, resulting in treks through exhausting backdrops that reflect James’ torment. I honestly respect that instead of making the game more mechanically “fun,” they doubled down on the dismal (aside from the fact you can i-frame dodge through Pyramid Head’s attacks like they’re a Devil May Cry boss, which is a little too satisfying). It’s dark, and I mean that quite literally; your flashlight is somehow even dinkier than before—you can’t see jack. And amidst all these changes that bring the game to a more outright serious place, that stupid pizza scene is gone entirely.

Sure, there are still traces of its former weirdness, like its difficult-to-achieve endings involving UFOs and manipulative Shiba Inus. There are also optional DLC masks, like a cardboard Pyramid Head, which you can make James wear for the whole game for some reason. I know this may sound pedantic, but these don’t count in the same way. They’re easter eggs instead of core elements of the experience, strange little accouterments that are cordoned off and non-canonical, a reference to this former vibe but not a wholesale endorsement of it.

In many ways, I can understand why Bloober Team went for this more serious approach with the remake. You can’t accidentally stumble into naive camp a second time, and intentional camp is a perilous tightrope that risks coming across as disingenuous or incomprehensible. It’s much more straightforward to be consistently bleak. After all, that’s what most people associate with the original anyway, even if that characterization is a little inaccurate. On top of this, the more solemn aesthetic squares nicely with many other modern prestige videogames that aim to shroud themselves in self-seriousness, something that I’m sure has been focus-tested across the medium or at least that’s supported by confirmation bias (The Last of Us sold well, so surely the next big prestige game will too). Yes, this may have led to a great deal of homogenization across big-budget games, but I don’t think publishers particularly care about that. And honestly, this game is pretty good at operating in this mode because, again, the vocal performances are crisp, and the camera work in the cutscenes is a cut above what’s found in most other AAA games.

Ultimately, though, my biggest issue with this different take has less to do with this game itself, which is perfectly entitled to bring this story in a new direction, than the culture and circumstances surrounding it. Compared to basically every other medium, there’s a tendency to talk about old games as if they’re obsolete and that this new wave of remakes is “fixing” what came before, like a software patch. I can understand where part of this outlook comes from in that game design and graphics visibly improve in some ways between console generations, but often, these changes are actually more like trade-offs. Graphics may have more fidelity now, but that doesn’t mean a new game has better aesthetic sensibilities than an old one. And perhaps even more importantly, this increased fidelity requires more labor to realize, which in turn costs more money and thus reduces the capability for creative risks.

And while remakes usually come with these pros and cons and are rarely the definitive version of the game, publishers frequently treat them like an out-and-out replacement. The original Silent Hill 2 is not remotely accessible. Physical copies of the game are exorbitantly expensive. You can’t get it on digital distribution platforms, and the only re-release is the Silent Hill HD Collection, which makes a bunch of baffling changes, like getting rid of this dreary New England town’s iconic fog. While there’s the fan-made Silent Hill 2 Enhanced Edition, a PC mod that makes the game run on modern hardware, you need to find a way to get the PC port (or at least its files) to make this work. The release of this new game means that it’s very unlikely Konami will go out of its way to change this accessibility situation because they likely perceive it could eat into the sales of the $70 remake, meaning only a small subset of new people will jump through the hoops to play the original. Maybe Konami never would have re-released it anyway, but now it feels lost in the fog.

In some ways, even if it’s an increasingly tedious trend, I can see why publishers are leaning so heavily into these kinds of remakes. Big-budget games have become very expensive, and these retreads are a much safer bet than creating something new and untested. On top of this, there’s certainly an appetite for them because they combine nostalgia and some degree of modernization— there’s no denying that by contemporary game design standards, many older games initially feel clunky and offputting, at least before you adjust.

But it’s in those oddities, those strange contradictions, where you can find many of the most interesting experiences the medium has ever produced. I have a hard time thinking of a better example of this than Silent Hill 2. It’s a game where every detail, whether intentional or not, adds up to create something genuinely unique. Here, masterfully sculpted psychological horror melds with weird bursts of camp, the two modes intertwined in a surreal, absurd din of stilted dialogue and haunting images. The Silent Hill 2 remake is good, but it has me asking an important question: where’d the pizza go?

Elijah Gonzalez is the assistant Games and TV Editor for Paste Magazine. In addition to playing and watching the latest on the small screen, he also loves film, creating large lists of media he’ll probably never actually get to, and dreaming of the day he finally gets through all the Like a Dragon games. He wants you to remember that even if you didn’t like the Silent Hill 2 remake, you shouldn’t harass the developers about it on social media. You can follow him on Twitter @eli_gonzalez11.