North America Is Finally Ready for The Tower of Druaga, 40 Years Later

Games Features tower of druaga

Namco’s seminal arcade hit, The Tower of Druaga, turns 40 this month. Four decades of a game that spawned a number of fascinating sequels, console and mobile spin-offs, a manga, and two seasons of an anime, never mind the influence it had on the games that were to come. And yet, outside of Japan—where Druaga released and thrived and most of all of the above was confined to for years, and, in too many cases, remains there alone to this day—you haven’t and won’t be hearing all that much about this important anniversary.

Having anyone from outside of Japan even acknowledge The Tower of Druaga is a rarity on its own. Sickos like me, sure, who would pitch a story like this to Paste, or those with independent publications looking deep at videogame history, but other mainstream outlets? It’s not a common topic. Even when Druaga does get a mention, it rarely discusses the game’s legacy and importance to both Namco and videogames as a medium. Which is a shame, given how extensive that importance is: Druaga shaped the action role-playing game and the dungeon crawler, while popularizing the concept of arcade games having a clear ending rather than looping forever. Its communal aspects—notebooks kept in the arcades where its cabinets lived, stuffed full of written hints and drawings explaining how to get past the challenges of each floor and where to find the hidden treasure of each, as well as what they did and were used for, filled out by the very people playing the game—were like a prototype for FromSoftware’s digital community of ghostly notes left behind by other players. Druaga is a title that Shigeru Miyamoto gushed over in a conversation with its creator, Masanobu Endo, aka the guy who also originated Xevious and changed shoot ‘em ups forever in the process. Miyamoto had Nintendo bring a Druaga cabinet into Nintendo’s offices, and was influenced in the creation of The Legend of Zelda by Druaga’s maze-like dungeon design, action-adventure elements, and item use—an earlier prototype of the game, per Miyamoto himself, was simply “a series of dungeons underneath Death Mountain,” a reverse tower, if you will, with the open-world aspects Zelda would become famous and foundational for added in later in development.

Rarest of all, however, is someone acknowledging that not only is The Tower of Druaga a foundational work, but that it’s also fun to play. While using the present tense, even. Sure, this is not a game that’s for everyone, but games that are for everyone are rarities. Super Metroid wasn’t for everyone, but that hasn’t dinged its reputation or lessened what the people who do seek it out experience. It’s easy to forget now, but From’s whole deal wasn’t for everyone for ages, either, and despite Elden Ring’s sales figures, still isn’t. Being for everyone is Mario’s job, and isn’t a standard every game needs to be held to in order to be deemed enjoyable or worthwhile.

Knowing that Druaga is fun is knowledge that’s difficult to come by, though. It’s 40 years old this month. It did not release in North America with the context that made it so significant in Japan years before—not only did other regions not receive the arcade version of the game nor its communal notebooks, but it took until the release of Namco Museum Vol. 3 on the Playstation for it to reach North America in any form. A representative aside: The Tower of Druaga is the first game on the list when you boot up that title, a sprite of its protagonist Gil used as a loading animation, but when the Greatest Hits edition of the game launched in North America, it was merely presented in the “Also includes” section instead of being front and center, or given equal space like on its original and Japanese releases. And the back of the case didn’t even mention it at all! Meanwhile, the art book released by Namco for this same compilation features Druaga art front-and-center, just like within the game itself.

Critics didn’t know what they were looking at here, and while there was a hint system used to help players along, it wasn’t quite as robust or as convenient as having access to a notebook and community, nor in comparison to later hint systems Namco would include with future releases of The Tower of Druaga. It would take until 2009 for the game to receive a solo release, on the Wii Virtual Console once they started adding arcade games in: as there were no hint systems, and we weren’t quite at a place where mainstream outlets having to rush around to review a bunch of retro releases every week had the time to really dig in and learn about what they were writing about, this release was panned, and its original context and importance remained a mystery to readers who might have been learning about it for the first time. Which is to say, the game faced a long, uphill battle for relevance outside of the territory in which it was already known.

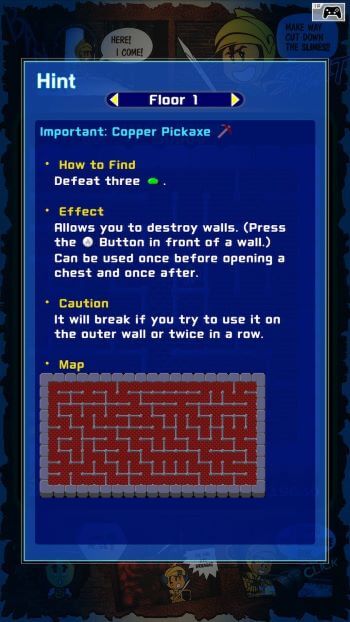

Luckily, Namco has learned from this, and future releases of The Tower of Druaga did more to attempt to capture the game’s original context. You do play on your own both physically and in spirit, unlike in 1984 in a Japanese arcade center, but to make up for that, there are now built-in hint systems, like in the Namco Museum for Nintendo Switch edition of the game, where you can pause the game to see a hint for the floor you’re on displayed at any time: one that will show you what the treasure hidden on the floor is, how to get it, and what it does. Given some treasures are required to finish the game and others could, say, poison you and kill you, so being able to learn about that sort of thing in advance is helpful.

It’s not just the hints. Druaga now features an optional, visible health bar—this was not a widely adopted practice at the time, not until after another influential Namco title, Dragon Buster, had landed—and will show you how many times you’ve used your pickaxe on a given level, which you need to know in order to keep from breaking it through overuse. You can change the number of lives you start with, lowering the difficulty a tad, like with any other Arcade Archives release. Essentially, everything Endo’s Game Studio put into home releases of Druaga—such as for the Game Boy and PC Engine—decades ago has been implemented into home releases of the arcade original, for the same reasons they were then. The context of these releases is different, the communal aspects the game was designed around nonexistent here, so the expectations for how you’ll make it through have to change, as well. That, and Endo later expressed some regret about just how much the treasure- and secret-seeking took center stage, so these changes were made to undo some of what he saw as damage he inflicted upon players’ psyches.

Even with these (optional) hints and tweaks in place, Tower of Druaga is a brutal game. The anime spun out of it based a (clever and funny) episode around the original concept of the arcade game, with various characters controlling the movements of the show’s primary protagonist and Gil stand-in as he explored the original Tower of Druaga, all while referencing a notebook that explained the secrets of every floor. The whole idea was a little nostalgia-based nod, sure, but it was also to point out that classic brutality that formed the game’s experience, even for adventurers who knew what needed to be done. Hey, you might know what you need to do in Elden Ring, too, but actually doing it is another thing entirely. This is no different, even if Gil has just a tad less agility than even the most overburdened Souls build.

You move slowly in Druaga, unless you get the boots that speed you up—luckily, they’re on the second floor, to teach you the value of not rushing through without exploring or experimenting. But you’re making your way through a maze, defeating and avoiding enemies as necessary, pressing down a button to hold out your sword as you walk and put your shield to the side to defend yourself from ranged attacks in those directions, or leaving your sword sheathed and your shield in front of you for the same. You’re seeking the key to open the door on each floor, as well as whatever treasure is hidden there, assuming it’s not one of the ones that will kill you, anyway. You’re racing against a timer, which isn’t just for achieving a higher score bonus at the end of a floor, but also to avoid having unkillable wisps arrive on the scene to hunt you down and end you and your quest—this is an arcade game from 1984, after all, and those did not want you tarrying for too long in one place when you could be progressing instead. It’s all old-school, slower paced, intentional design in every sense of the phrase, but if you’ve got those hints in place and the patience to slowly unravel this 60-floor puzzle that will see you ascend Druaga’s tower to rescue the priestess, Ki, and recover the stolen Blue Crystal Rod that belongs to Ishtar in the heavens, well… You’re going to enjoy this, so long as you give it the chance that it merits.

Consider that when Druaga got its first solo North American release, those aforementioned Souls games that pulled from Druaga’s design and philosophy weren’t here yet: Demon’s Souls would land on the Playstation 3 months later, and it would take quite a few of them before it was understood by the masses just what they were asking of you. Roguelikes, at the time, remained incredibly niche, far more so than now. The normalization and wider acceptance of those two genres that occurred in the 15 years since, combined with Namco’s improved, hint-laden Druaga releases, means the timing is right for you to ignore the haters from 2009 and dig in for yourself, to see that this vital piece of videogame history, this foundational release from four decades ago, remains as enjoyable as Namco’s other arcade classics you could apply similar labels. If not, in some cases, even more so.

Marc Normandin covers retro videogames at Retro XP, which you can read for free but support through his Patreon, and can be found on Twitter at @Marc_Normandin.