Boss Rush: Tunic’s “Golden Path” Is a Brain-Bending Final Challenge

Subscriber Exclusive

Frequently, at the end of a videogame level, there’s a big dude who really wants to kill you. Boss Rush is a column about the most memorable examples of these, whether they challenged us with tough-as-nails attack patterns, introduced visually unforgettable sequences, or because they delivered monologues that left a mark. Sometimes, we’ll even discuss more abstract examples, like a rhetorical throwdown or a tricky final puzzle or all those damn guitar solos in “Green Grass and High Tides.”

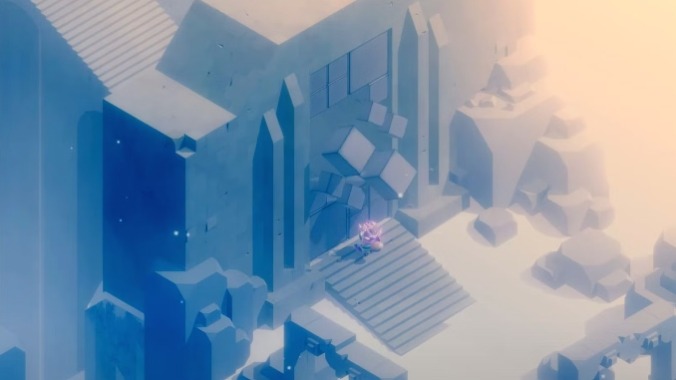

At first glance, you’d be forgiven for assuming that Tunic, an isometric action game from developer Andrew Shouldice, is a Legend of Zelda “clone.” As its title suggests, the protagonist wears a green tunic that calls to mind a certain Hylian hero, it features action gameplay that is quite similar to those experiences (with some FromSoftware-inspired touches for good measure), and it’s also set in a fantastical world where your main goal appears to be rescuing a damsel in distress.

But while these influences are undeniable, as you dig deeper, it becomes clear that there’s something different going on here. Even compared to the old-school works it’s drawing on, like the original The Legend of Zelda, the game offers little overt explanation. Most of the signage and dialogue are in an in-universe language you don’t understand, forcing you to intuit what’s happening and what you’re supposed to do.

Eventually, you begin to find Instruction Manual Pages scattered throughout the world, which as the name suggests, provide details on how to play. And although some of the text here is translated, explaining particulars like how you take more damage when your stamina is low, much of this is still in unfamiliar language that leaves many gameplay details and the story a mystery to be uncovered.

Despite this, the basic framing of this tale eventually begins to sink in. Your character, an unnamed anthropomorphic fox, explores the ruins of a destroyed civilization to rescue a fox spirit, referred to as “the Heir” in the manual, who is trapped in a magical prison. To free them, you face challenges and do the classic videogame thing of finding a bunch of MacGuffins (three keys hidden in the far corners of the world, in this case). However, after opening the Heir’s cell with these keys, something unexpected happens: the person you’ve been trying to save summons a giant sword before promptly demolishing our protagonist. To get a rematch, you need to go on a new quest to reclaim the fragments of your soul.

After more trials, our protagonist battles them a second time in what seems like the final boss fight, but after defeating them, we get another twist; our hero’s reward is that they take the Heir’s place, becoming the next vessel to hold this world in a state of limbo. If the imagery of your little fox protagonist becoming trapped in an interdimensional prison wasn’t gloomy enough, the foreboding score makes it clear this is a “bad ending” of sorts, the kind that can hopefully be avoided. Thankfully, you’re given the chance to reset things before this encounter and explore the world further.

By this point, Tunic had already largely broken out of the shadow of its inspiration. While it was structurally similar to traditional Legend of Zelda entries, and its first ending involved a big climactic battle like, well, most videogames, its focus on creating moments of quiet discovery differentiated it from the pack. You’d constantly come upon strange sights: sealed doors with enigmatic symbols, odd yellow platforms, or obelisks that seem to have some greater purpose. Although progression was sometimes gated by specific items, like a grappling hook, more often, you’d be blocked by a lack of knowledge, such as how to properly interact with the previously mentioned relics. Perhaps the best example of this is something referred to in-game as the “Holy Cross.”

To kickstart this realization, you find a page that shows the following: a picture of a D-pad, a series of arrows that correspond with directional inputs, and a picture of a door with a maze-like symbol. Once you have these clues, it clicks; the series of squiggles on the door represent directions on the D-pad—basically, you need to trace a path through the maze depicted on this object. Again, you’re never explicitly told, “Hey, the ‘Holy Cross’ refers to performing a Konami code-esque sequence when you see these patterns on doors or obelisks,” it’s something you find out for yourself, and it’s all the more rewarding for it. Once you figure this out, doors literally and figuratively open for you.

But while Tunic emphasizes discovery throughout, it goes all in on these elements after you’ve seen the “bad ending,” putting combat on the back burner as you face the true final boss: a big door. Or, more specifically, the game’s last major challenge is an intricate, world-spanning puzzle, referred to as “The Golden Path,” that you need to traverse to open this last gate.

The Door in the Mountains sits in the middle of the overworld map. Like most of the game’s strange sights, you’ll probably see it hours before you know what to make of it. But eventually, you find a manual page with a hint, a grid of numbers. The main tell for what this means is that at the bottom, there’s a circle with a line coming out of it that leads into the grid. After some thinking, its meaning becomes clear—the dot with the line coming out of it looks exactly like the symbol for the beginning of the Holy Cross, meaning this door can also be opened with a series of D-pad inputs that trace the path of a maze. The problem is that the manual page doesn’t have a line that can be traced; it has a grid of numbers.