Andrei Tarkovsky always worked to set himself apart from his home country. During a 1972 conservation with Soviet film critic Leonid Kozlov, Tarkovsky wrote up a quick list of his ten favorite films. On it were the likes of Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari, Buñuel’s Nazarin, as well as two by Bresson and a whopping three films by Ingmar Bergman. Kozlov, later reflecting on the severity of the list, noted that there was only one silent film (Chaplin’s City Lights) and not a single work from the USSR. He posited it was because Tarkovsky believed that “real film-making [was] something that went on elsewhere.” Tarkovsky’s personal resentment against the USSR, whose state media bureaucracy he spent an inordinate amount of time battling, however, undermines the rich and poetic cinema that was happening before and alongside him—a filmmaker who would go on to be seen as the sole voice of that kind of film art in his massive country. But there’s more complexity to his preferences, especially regarding his Soviet peers.

Pouring over writings and interviews, I have compiled a list of some of Tarkovsky’s favorite films from the Soviet Union. In it we see a surprisingly diverse collection of unique, striking and, of course, poetic filmmakers finding new voices inspired by one old master. These films offer a glimpse into a Soviet film tendency that emerged after the death of Stalin in a moment of new artistic freedoms that was open and shut barely a decade after it began. It’s the story of a generation of filmmakers, not with Tarkovsky as their sole voice, but as one of many filmmakers pioneering a new kind of cinema.

Here are Andrei Tarkovsky’s favorite Soviet films:

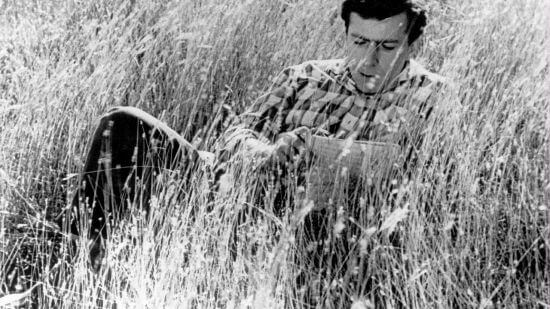

Earth (1930)

There should be no speaking of Tarkovsky’s favorite films of any stripe without talking about Earth and Aleksandr Dovzhenko. Tarkovsky was never the biggest fan of silent cinema, seeing it as a forerunner to film’s true potential when the dimension of sound was added. But while the Soviet pioneers are often thought of in terms of the mathematical montage of Kuleshov and Eisenstein, Dovzhenko’s films reached for something more naturalistic in story and dreamlike in rhythm—it is Earth that Tarkovsky is talking about in his much-memed clip of him saying “Poetic cinema.” More than any of the other filmmakers on this list, I will leave it to Tarkovsky’s own words:

“I love Aleksandr Dovzhenko very much. I believe he is a genius. He created a film which I have not stopped watching over and over again to this day; that is Earth. I cannot explain why this film touches me so deeply. The film may be naive in many ways, too schematic, rather roughly composed. But—the attention of this film is focused on the workingman who tills the land he lives on. And that surely is one of the noblest professions on earth. I probably did not express it accurately, I mean this profession ennobles people. I have lived a lot among very simple farmers and met extraordinary people. They spread calmness, had such tact, they conveyed a feeling of dignity and wisdom that I have seldom come across on such a scale. Dovzhenko had obviously understood wherein the sense of life resides. And he addressed an issue that has left a lasting impression on me. This trespassing of the border between nature and mankind is an ideal place for the existence of man. Dovzhenko understood this. I think about him a lot—he forces me to think about him. Dovzhenko not only gives the impression of being a director. He is a philosopher.” (From a 1973 interview with Günter Netzeband)

Falling Leaves (1966) and Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird (1970)

One of the contemporaries Tarkovsky rated most highly was Otar Iosseliani. The Georgian filmmaker is, next to Tarkovsky, perhaps the greatest heir to Dovzhenko’s poetic stylings. His first feature, Falling Leaves, opens with an eight-minute, dialogue-free sequence of Georgian villagers going through the whole of their traditional, ancient wine-making process: From harvesting grapes to mashing them with their feet, distilling chacha out of the pomace, aging the ferment in qvevri underground, to serving the final product in a big supra with all those involved. It’s a truly loving sequence that seems like it rips Dovzhenko’s pastoral poetry from the wheat fields of Ukraine to the mountains of Georgia.

The other of Iosseliani’s films that Tarkovsky holds near and dear above all the rest is his follow-up, Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird, a picaresque of an orchestra drummer in modern Tbilisi who can’t be bothered to show up to work on time or hold down many relationships. Iosseliani weaves the wanderings of this Soviet bohemian with a cool, gliding camera whose motion is only matched by the movement of the protagonist and the effortlessness of his editing. For not even being 80 minutes, the film is a stunning breeze, with youthful disaffection flowing in and out of the pace of the modern world colliding with a highly traditional culture.

Pirosmani (1969)

If there was ever a royal family (or whatever the Soviet socialist equivalent for royalty is) for Georgian film, it is the Shengelaias. Born to film director Nikoloz Shengelaia and silent film star Nato Vachnadze, Giorgi and his brother Eldar would be two of the most prominent film artists in Georgia from the ‘60s all the way through the country’s independence, where Eldar would go on to have a successful political career as well. For Tarkovsky, Giorgi’s film Pirosmani was the standout, and it is easy to see why it appealed to Tarkovsky’s tastes.

Following the story of the posthumously famed turn-of-the-century painter, Pirosmani is a film about artists as they relate not just to their culture, but the culture of art that stands over all of it. As Niko Pirosmani wanders around the countryside and eventually into the city, he paints as an odd job to make ends meet, while, unbeknownst to him, a pair of cultural movers-and-shakers are in pursuit of the artist to buy up his work and make him famous. For Pirosmani, this was never the purpose of art—first he painted to have something nice on his shop’s facade to attract customers, and soon he was making the lowest taverns in Tbilisi into some of the finest art galleries with his paintings that once lived with the masses. It explores a similar relationship between artists and the world as Rublev, but does so in the opposite manner of production: Where Rublev is epic, sprawling and even maximalist at times, Pirosmani is small, personal and never leaves the bounds of its deceptively simple compositions. Pirosmani’s flattened, surreally rendered images are brought to life by Shengelaia’s camera, which uses the unnatural tones inherent in Sovcolor film stock and some outstanding set design to form some of the most painterly images in the history of cinema.

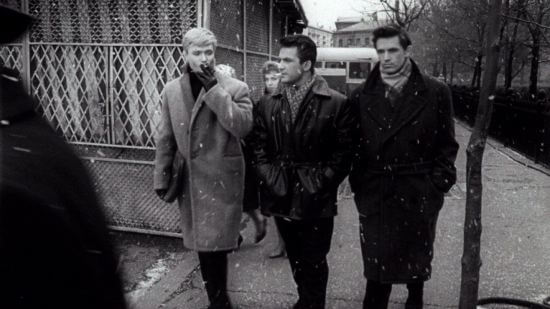

I Am Twenty (1965) and July Rain (1967)

In a 1970 interview Tarkovsky was asked about which of his Soviet contemporaries he admired. He found it to be a difficult question to answer given that he thought many of his colleagues were still so young, and even the most talented ones had yet to make their best films. However, one only seven years his senior sprung to mind, one who had gotten a jumpstart in filmmaking right as artistic repression had let up after the death of Stalin.

Before Tarkovsky smashed onto the film scene with his debut Ivan’s Childhood, he played a bit role as a drunken party guest acting as a foil to the intelligent but proletarian hero of the film in Marlen Khutsiev’s seminal Thaw-era work I Am Twenty alongside his writing partner at the time, Andrei Konchalovsky. While Konchalovsky and Tarkovsky would have a falling out during the making of Andrei Rublev (the excess of Andreis did not go unnoticed here, a student-made behind-the-scenes film of the production was actually called The Three Andreis), Tarkovsky kept admiration for Khutsiev’s films as time went on. I Am Twenty is a film about a disillusioned generation of youth coming of age after the war, one both literally and symbolically fatherless, who, despite still being ardent socialists, can’t seem to find their way in a state that’s reached some kind of stagnation. It was the last of its kind in a moment of new political openness, and Khutsiev’s follow-up July Rain would prove to be an even more lonely, isolated and bleak portrayal of contemporary life in the USSR, following a woman in identity crisis as she starts to find pointlessness all around her, in her love life, work and friendships. It’s a film of stark black-and-white cities and missed phone calls, and as Khutsiev’s style evolved, it became the closest a Soviet film ever did to being an Antonioni picture. (And as a bonus aside, Khutsiev was also a Tbilisi-born Georgian.)

Twenty Days Without War (1977)

If there was ever a Soviet filmmaker who could match the ethereal visual stylings of Tarkovsky, it was the Leningrad-based filmmaker Aleksei German. Son of the famed genre novelist Yuri German, Aleksei was unlike most of the Russian greats of his generation who came up through VGIK, Moscow’s film school, the oldest in the world. Instead, German studied directing at the Leningrad Institute for Stage Arts before moving to Lenfilm, the second largest studio in the Soviet Union. His stage knowledge comes through in his intricate mise en scène, where characters seem to have almost a dreamlike relationship to their environments as they weave in and out of frame.

German too struggled with the censors: His first solo directorial effort, Trial on the Road, was banned until perestroika in the mid-’80s, and from the mid-’70s onward would barely complete a movie a decade. While I have seen it referenced that Tarkovsky called German’s 1985 masterpiece My Friend Ivan Lapshin “the greatest Soviet film ever made,” I’ve never found a primary source for this (although I’m sure he did admire that film). Instead I’d like to highlight another film Tarkovsky definitely mentioned in an interview from the early ‘80s, where he called German the third best of his contemporaries: Twenty Days Without War. This grossly underseen film follows soldiers going on leave and traveling far away from the brutal fronts of World War II to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. Even though they are a week’s train journey from the battle lines, the devastating efforts of the war are still ever present, and the bleak, muddy black-and-white world seems as ghostly as German’s wandering camera.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1965) and The Color of Pomegranates (1969)

There was no Soviet artist who had as close a relationship to Tarkovsky as Sergei Parajanov. The Tbilisi-born Armenian started his career as a rather banal filmmaker within the socialist realist tradition, but after seeing Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood a lightbulb went off for him. His next films immediately transformed into works of poetry and portraiture, starting with Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, a story of star-crossed lovers in the Carpathian Mountains of Ukraine. Parajanov’s gaze here is poetic without being opaque, it’s quite the opposite—his symbolism is incredibly specific and ethnographic, possibly making it seem even more impenetrable at first glance. However, like Tarkovsky’s films, Parajanov’s style is one the viewer must surrender themselves to to experience.

His next film, which many argue as one of the great masterpieces to come out of the USSR, The Color of Pomegranates takes Parajanov’s style to even further extremes, eschewing conventional narrative altogether and instead telling the biography of a poet through a style of filmmaking that can only be described as poetry in motion. It is an audiovisual feast for the senses, where the audience is guided from composition to composition not strung together as a coherent set of sequences, but like they are passing through a carefully curated art gallery of paintings in motion. It’s a unique achievement, and a style that Parajanov would continue to use in his last films. Sadly, he was jailed (again) in the 1970s for his bisexuality, and struggled to get back into film production until the 1980s. And while Ivan’s Childhood pushed Parajanov to become the artist he ultimately became, Tarkovsky would become equally inspired by his friend’s works as their careers moved along. More than inspirations for each other, they were good friends. One of my favorite anecdotes about the pair was observed by documentarian Yuri Mechitov at a dinner party hosted by Parajanov, who was telling Tarkovsky, “Andrei, you are undoubtedly a talented director, a very talented one, but…you are not a genius.” This made Tarkovsky hold his breath. “Because you are not a homosexual and you’ve never been jailed.”

Alex Lei is a writer and filmmaker. Born in Portland, OR, he got a BA in film from Montana State University, and after working in politics for a time relocated to Baltimore. He spends his days working behind bar, endlessly editing old projects, researching new ones, and occasionally putting out writing. Words can usually be found at Frameland, Splice Today, his newsletter CompCin for longer-form writing, and Twitter for things that are barely written at all.