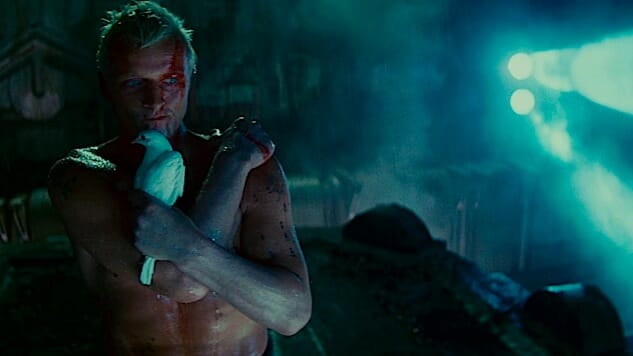

Blade Runner: Twice as Bright, Half as Long

Blade Runner demands to know why our creators made us mortal in an age of wonders

(Note: Like all proper examinations of this film ought, this article refers to the 2007 “Final Cut” 25th anniversary version of Blade Runner, with the exception of the following quote.)

Roy:I want more life … fucker.

Why do we create? It’s not accurate to say that only humans make things, but there’s a difference between an anthill or beaver dam and, say, a film about humanity’s pathological drive to leave its mark on the world, even when doing so results in a new form of intelligent life. A form of life that is terrified of and vindictive toward its imperfect creator—that demands to know why we promised it the world and didn’t give it enough time to live in that world.

Lay aside for a minute that Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) is the beginning and ending of cinematic cyberpunk, of futuristic urban dystopia, of artificial intelligence rebelling against its creators. Lay aside that there is not an uninteresting or uninspired shot in the entire experience. Lay aside that it is really cool. It is also the cry of every emerging adolescent frustrated with the platitudes of Sunday school, every person laboring under the grinding unfairness of an illness for which there is no cure, every unwanted child at the utter mercy of parents who don’t know what the hell they’re doing. Deicidal rage at an imperfect creator’s unfairness is something too subversive for most blockbuster films, even in this world awash in daddy issues.

Our progenitors (biological and divine) bring us into the world without any idea of how long we have in it, or why we’re here. Blade Runner’s angry demand is: In this age of wonder, why don’t we? Why were we made flawed? Why can’t we fix ourselves?

Why can’t we just have more time?

Rachael: It seems you feel our work is not a benefit to the public.

Deckard: Replicants are like any other machine. They’re either a benefit or a hazard. If they’re a benefit, it’s not my problem.

Blade Runner takes us to the distant, distant future of 2020, where cars fly over an oppressive cityscape and buildings belch plumes of flame beneath a smoggy sky that has forgotten what the sun looks like. In this future, Earth is overpopulated and humanity is taking to the stars—and employed bio-engineered, human-like constructs called “replicants” to do the dangerous work of settling suitable planets. But, the expository crawl at the beginning reveals, these replicants have become more and more advanced, in some cases becoming mentally and physically superior to their creators. After some of them rise in bloody rebellion, they are outlawed on Earth on pain of death. To “retire” these defective machines that look and feel like humans, police departments form a special class of replicant-hunting detectives called “blade runners” (a name with no rationale, it seems, other than it being an unspeakably cool thing to get to put on one’s résumé).

The newest model of replicant is so advanced that the only way to distinguish it from normal humans (without vivisecting it, maybe?) is to subject it to a profoundly weird psychological examination involving a machine that monitors the potential android’s eye as the blade runner bombards it with surreal hypothetical questions. We witness this emotional stress test on a corporate worker named Leon (Brion James), who, it turns out, is a replicant and was packing a surprisingly powerful handgun the entire time.

From there, we join ex-blade runner Deckard (Harrison Ford), interrupted in the midst of his lonely meal to get dragged back to his old police chief and coerced into coming back on the job to replace the blade runner shot in the first scene. Five replicants escaped from an off-world colony and crashed on Earth, and they’re trying to break into the corporation that made them. As Captain Bryant (M. Emmett Walsh) explains, their creators have tried to mitigate the possibility of them becoming emotionally aware by building in a rather harsh planned obsolescence: A four-year life span, with a ticking clock the replicants can’t see.

(Infuriatingly, Bryant only ever lists four replicants in this scene. Some have pointed toward a major spoiler as being the reason for him saying “five,” but adopting that logic doesn’t do a thing to make that make sense.)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-