The Weekend Watch: Portrait of Jason

Subscriber Exclusive

Welcome to The Weekend Watch, a weekly column focusing on a movie—new, old or somewhere in between, but out either in theaters or on a streaming service near you—worth catching on a cozy Friday night or a lazy Sunday morning. Comments welcome!

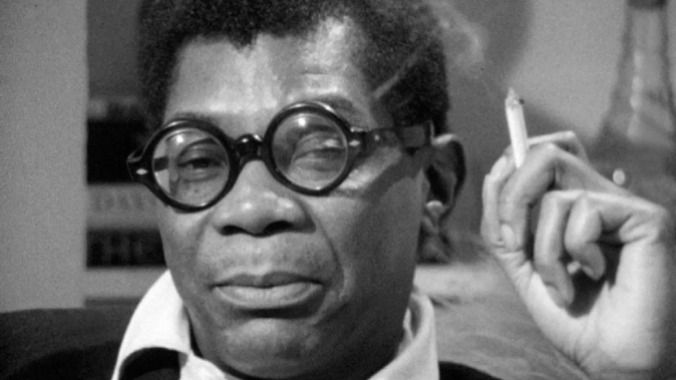

As we get into June, The Weekend Watch continues its focus on queer cinema, this time with one of its classic and most idiosyncratic examinations of queer identity. Portrait of Jason—the 1967 documentary you can find streaming on the Criterion Channel, on your local library’s app Kanopy, or for rent on all the usual services—is all about self-invention, protection and cultivation. Shirley Clarke’s interview with an increasingly intoxicated Jason Holliday AKA Aaron Payne is a revelatory look at the coping mechanisms, and reclamation strategies, of a queer Black man in ‘60s America. At the same time, it paints a much less flattering portrait of filmmakers who are pushing, pushing, pushing—perhaps past the point of artistic integrity and into the realm of boozy, leering exploitation.

That push, from director Clarke and her partner Carl Lee, is included in the relatively vérité film. We hear the two berate Jason off-screen, bringing up times he stiffed them, screwed them over, lied to their faces, lost their cash. We watch as Jason keeps slamming cocktails, dancing the drinker’s familiar steps—laughing, weeping, blabbing, gloating, falling, lying—in whatever order he pleases. These moments add shades of detail and production-based complication to a florid evening of storytelling already layered with complexity. The sensory ephemera of the film’s making-of is so intertwined with what was made that it has inspired its own script-flipping fictionalization, in Stephen Winter’s Jason and Shirley, which offers another angle to a film that already dazzles you with its endlessly glinting facets.

Yes, Portrait of Jason is nonfiction. There’s no script, no “actors” or “roles.” But it’s also…just as fictional as most documentaries. It’s a man, telling stories about his life, in a small room filled with people supplying him with questions, barbs and alcohol. Some of these stories are whoppers, some contain truth so essential they cut to the bone. But at least these are more up-front than so much of what’s currently presented as nonfiction, either in documentary films, reality romance shows or true-crime TV.

Portrait of Jason is part interview and part performance piece, in that you never doubt for a second that Jason has been performing every second of every day for as long as he can remember. It’s also a complete power struggle, between subject and interviewer, between performer and director, between the asker and the teller. In both this wrestling match for power and its clarity with which it addresses performance as a survival mechanism for queer men, Black men and, especially, queer Black men, Portrait of Jason taps into the sociology of queerness like few other movies ever have. Identities are invented for a reason, and exist as long as they are performed.

Through Jason’s life, whether it takes the form of a story about hustling or a memory around growing up broke or a small impression of Mae West (which, yes, is part of his life as an aspiring nightclub diva), he conjures that wonderful universalizing magic that uses ultra-personal details as its reagents. None of us may match the sheer comfort Jason has quipping in front of a crowd, luxuriating in their gaze, but we have all felt the isolation and panic he has felt, and put up some version of the walls he has erected to defend against them.

Reflected in his thick glasses, or reverberating from his inscrutable (yet always handy) laugh, we see ourselves. Our sadnesses and fears, our desires to simply be ourselves—whatever that may mean. Questions of authenticity fade as we grow more comfortable with the masks Jason wears, and the roles he plays. His collection of personalities and anecdotes and impressions and songs, they’re no different than the bricolage of traits we cobble together each day as we present ourselves to the world. He’s just more flashy, and maybe more honest, about it.

As you watch Portrait of Jason, you will be forced to grapple with Clarke’s production practices. You’ll be moved by Jason’s emotional trajectory. You’ll make up your mind about who these people were, and their relationships to one another, and to the world they lived in. And when you come up for air, your mind relaxing a bit after being completely captured by one of the most charismatic voices ever filmed, these complexities will sit easy. They will feel like second nature, these hard truths and profound observations. Of course we act like this, think like that, live through these scrappy means. It’ll all fall into place with the certainty of someone stumbling away from a barfly they’d just gotten a little too deep with on a Saturday night. That’s the power of leaving in the messy frayed edges of the filmmaking process, the power of asking leading questions through the very form of your movie. It’s the power of Jason Holliday.

Jacob Oller is Movies Editor at Paste Magazine. You can follow him on Twitter at @jacoboller.

For all the latest movie news, reviews, lists and features, follow @PasteMovies.