Searching For My White Thunderbird: 50 Years of American Graffiti

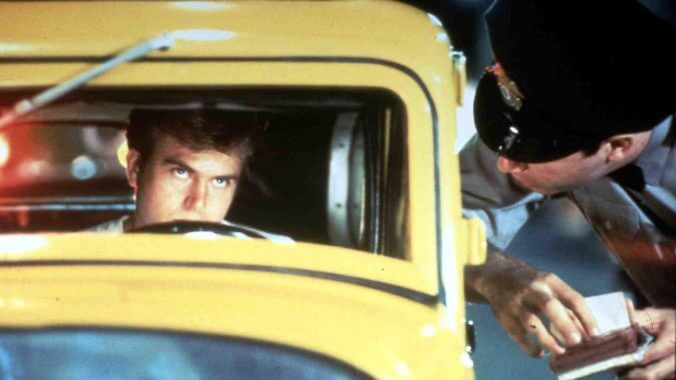

Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images Movies Features George Lucas

One summer many years ago, as firecrackers and bottle rockets painted the 4th of July air a technicolor flame outside our house, my dad ushered me into the living room and put his DVD of American Graffiti on the TV set. He said something along the lines of “I want to share this with you,” or at least that’s what I’ve chosen to remember him saying. I was maybe nine or 10, not yet aware of puberty’s massacre or high school’s plague of pimply-faced misanthropy. I was merely an overweight pre-tween who loved baseball, Superman-flavored ice cream, and rock ‘n’ roll. Life was euphoric, even if the country was in a recession and everything beyond the utopian, poster-filled walls of my shoebox-sized bedroom was, to put it frankly, fucked.

My dad has passed a lot of obsessions onto me: baseball cards, Motown, problematic comedies from the 1980s, the Bee Gees, Saturday Night Live, and the ever-agonizing destiny of loving Cleveland sports teams. But no gift has ever been as talismanic as American Graffiti, George Lucas’ second feature film—which was released in 1973, four years before he made Star Wars. It’s a coming-of-age film my dad, in no way, shape, or form, could actually relate to. It takes place in 1962—a full year before he was born—in Modesto, California—2,500 miles from Southington, Ohio, where he grew up. Yet, that wasn’t the point (it never is). The magic that exudes from every second of American Graffiti is what he latched onto—and it’s what I became obsessed with, too.

But the version of American Graffiti that has become canonized in my life is not the one that is canonized in my dad’s. He doesn’t acknowledge the existence of the sequel, More American Graffiti—which came out in 1979 and was massively panned by critics—but I do. He prefers to consider the picturesque perfection of the first movie and remain blissfully ignorant to the story’s forthcoming tragedy, but that’s too easy of a life to live. Perhaps it’s less of a burden for him to look at a pre-Vietnam War world and demand to live in it for as long as he possibly can (my dad’s formative years did hit just as the war reached a boiling point at the turn of the 1970s), or, perhaps, it is my own narrow-sighted opinion of what heartache and death and sickness really is that has rendered me forever desensitized to grief. It’s what allows me to enter the full world of American Graffiti rather than just its first chapter, but not all that glitters is gold.

American Graffiti is a 112-minute depiction of six friends’ last night of summer before Steve (Ron Howard) and Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) are set to head east for college. The way Lucas presents this solstice finale is eons different from the ones I lived through as a freshly graduated 18-year-old. There was no grand celebration of my final gasp of pre-undergrad freedom; only a high school romance ending in a driveway and a whole mess of anxiety about moving to a new place where I knew not a single soul. But that’s not to say that what American Graffiti offers its viewers isn’t what actually happened 60 years ago—especially in Southern California, which was always lightyears cooler than the rural Midwest.

At the end of American Graffiti, we learn a few truths about our four leading men: In 1964, Milner (Paul Le Mat) is killed by a drunk driver; in 1965, Toad (Charles Martin Smith) is reported missing in action while serving in Vietnam; in 1967, Steve is an insurance agent; Curt migrated to Canada and became a novelist. In More American Graffiti, those truths get fleshed out even more: Toad faked his death in order to escape combat, while Steve and Laurie’s marriage is spiraling as they navigate parenthood and sexism in suburbia.

What is most compelling about the story of American Graffiti, however, is the way in which the film (and its sequel) are eulogizing a moment we never actually see happen on-screen. Milner’s untimely death on New Year’s Eve in 1963 looms heavily on both movies, even if the event isn’t revealed until American Graffiti’s post-script and we only get to see him drive off into an empty highway he will never leave in More American Graffiti. Throughout the latter, we watch four friends navigate life after Milner’s passing while also watching his final day alive unfold. It’s one of the best uses of dramatic irony in all of cinema—and you can see so vividly how, even though our heroes no longer cross paths, they are bound together by Milner’s presence and, then, his untimely absence. I often consider how, beneath the gauzy, pretty surface of late-night West Coast pastorals and chart-topping doo-wop and rock tunes, there is a pretty stark and lonesome story of grief bubbling. Just as we are tasked with watching the joy of being a teenager in mid-century Modesto fade away through Milner’s point-of-view, we must later reckon with the heaviness of his passing through his friends who survived him.

Two years prior to making American Graffiti, Lucas made THX-1138—but the film failed to reach broader audiences, only bringing in $2.4 million at the box office. It was when Francis Ford Coppola dared Lucas to write a screenplay with a wider reach and more domestic appeal that American Graffiti was born—and Coppola would later serve as the movie’s producer. The blueprint that Lucas had created paved the way for films like Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Dazed and Confused and Almost Famous—films that examined teenagerdom through an emphasis on era-contingent music and the societal forecasts of young people at the time.

For American Graffiti, that theme centered around masculinity and the expectations that are thrown at 18-year-old men. Some folks argue that nothing happens in the film, but I argue that the it is one of the greatest depictions of three juxtaposing paths that confronted men at the time: Enlisting in suburban rebellion by never letting go of your youth, getting drafted into the soon-to-be Vietnam War, and the capitalistic pressures of finding a life’s purpose through a soul-sucking job. The entire central plotline of the film is about Curt considering what it would mean to not leave for college the next day, and he spends his final night in the Valley committing crimes with the Pharaohs, a gang of kids who ride around in a 1951 Mercury coupe. Milner, in particular, comments—multiple times—on the cruising strip’s march towards death. “The whole city’s shrinking,” he laments within the first 10 minutes of the film. The world around him is folding inwards, his peers are hightailing towards the coasts, and there he is, stuck drag-racing out-of-town chumps for an exhausted, fameless title.

What continues to define American Graffiti’s legacy is two-fold. One, the 40+ oldies that play on-screen make up, what is widely regarded as, one of the greatest film soundtracks of all-time. (The songs from Chuck Berry, The Platters, Fats Domino, The Skyliners, and countless others are still timeless.) Two, some of the biggest actors of the 1970s—Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, Harrison Ford and Cindy Williams—flirted with stardom here in unparalleled ways. By the end of the decade, Dreyfuss would play a lead in Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind and win an Oscar for The Goodbye Girl, Howard would get huge with Happy Days before transitioning to directorial work full-time, Williams would star in the Happy Days spin-off Laverne & Shirley, and Ford would assume the role of Han Solo in Star Wars.

Looking back, it’s unbelievable that the only proven actor of the bunch in 1973 was Howard, who’d played Opie Taylor for eight years on The Andy Griffith Show (Dreyfuss had one line in The Graduate in 1967, but not much else). But, then again, the practically unfamous cast of American Graffiti is what helps make the film so believable. Though nearly every main actor was older than the age of the character they were playing, their inexperience in front of a camera gave them a deftly uncanny rawness. It felt like we were watching teens come of age on-screen. The energy of the film was “you can’t stay 17 forever,” and each cast member was able to tap into that truth with such enduring potency. 50 years later, it’s still one of the best ensemble performances in movie history—and, possibly, the best smash hit to never win an Oscar (it was nominated for five of them, including Best Picture, but lost out to The Sting, among others).

From the very first frame of American Graffiti, when we are greeted by a shot of Mel’s Drive-In—referred to, affectionately, as Burger City in the movie—and Bill Haley & the Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” rings out and the opening credit font is tricked out in neon signage, I could feel the magic of what was, to me, a bygone era. It’s important to understand what was happening in 1962: The Dodgers had only been in Los Angeles for four seasons, Beatlemania was still two years away, Kennedy was alive and in the White House, and Lawrence of Arabia was raking in millions. There’s also a great, generational dig at the burgeoning surf-rock craze of the time where, as a Beach Boys song plays on the radio, Milner tells Carol (Mackenzie Phillips) that rock ‘n’ roll has been falling apart ever since Buddy Holly died.

American Graffiti has everything: drag races, theft, gangs, rock ‘n’ roll, fooling around in cars, puking, a burger called a “chubby chuck,” melting popsicles, a very famous disc jockey, pinball machines, junkyards, roller-skating waitresses, scholarships, a freshman hop, cigarette smoking, and, most importantly, cruising, cruising, and more cruising. You might be asking yourself, “How can all of that be in a sub-two-hour movie?” Well, kids of the Silent Generation could achieve anything, clearly! But, if you’ve ever lived off the high of doing the most batshit hijinks at 3 AM, then you can, probably, understand how six teenagers were able to plug an entire summer into one night. Yet, as a 10-year-old kid who never hung out with anyone outside of pee-wee football practice, the hours in American Graffiti felt especially retro.

You couldn’t make American Graffiti in 2023, simply because no one goes “cruising” anymore—at least not in the way the Modesto kids did 60 years ago. I used to think that, when my friends and I would hop in our rusted-out, used-car-lot rides and speed down hilly backroads with every window down, we were siphoning from the same high that pumps blood into the heart of Lucas’ masterpiece. Maybe back then it did feel like that, earnestly. A decade removed from those days, though, it’s easy to see that we were just driving to and from Burger King, sparking bowls at traffic lights, and finding a reason to use an aux cord. The only time I ever really came close to the destiny of American Graffiti was when my best bud and I once loaded into my car—after our high school’s basketball team took down a much better rival in an unlikely blowout victory—and drove with the windows down through an out-of-place, early February thunderstorm.

But the part of American Graffiti I am drawn to the most these days is its sketching of language. Much of the film’s communication happens from inside cars. One of the best lines comes when Milner sees a buddy driving next to him and asks “What happened to your flathead?” and the guy across the road yells back “Ah, your mother!” In an earlier scene, Toad—while driving Steve’s beautiful 1958 Chevy Impala—proudly asks a tough guy “What’ya got in there, kid?” while stopping at a red light, only to get a response of “More than you can handle.” Whether it’s conversations happening between a driver and a passenger, or a group of kids yelling at each other while voyaging in circles around town, or a stranger mooning another stranger by pressing his ass up against a backseat window, there are these grand declarations of affection, shit-talking, and camaraderie that happens solely in the space between two moving automobiles. It is very much a depiction of somebody’s American Dream, but it’s also a very strong projection of isolation, as a barrier is set up through car windows and street lanes.

For as jam-packed with dialogue, energy and charisma as the story of American Graffiti is, it’s an incredibly lonely movie to watch unfold—as these half-dozen characters have just graduated high school into the country’s first real identity crisis since World War II. As someone who lived through the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars and graduated college into the apex of a global pandemic, I get why Milner struggled to, finally, stop being a 22-year-old teenager and start being a 22-year-old adult and why Curt, in the final hours of his last gasp of adolescent freedom, began questioning if giving it all up was even worth it to begin with. It’s difficult to embrace the rest of your life when the world can’t make room for it.

My dad and I wore out his copy of the movie over the years. As far as I know, he still has it in the DVD closet in his and my mom’s living room back in Southington. I, on the other hand, upgraded to a Blu-ray copy once I moved to Columbus after college. Watching American Graffiti was a yearly tradition, almost always around Independence Day. It was an unspoken ritual that never needed any initiation. I’d hear “Rock Around the Clock” blare—and I mean scream—out of the speakers of our surround-sound system and go running. My dad is a notorious TV talker—I’m talking horrible and apocalyptically annoying—but, when he’d put on American Graffiti, it was like he suddenly had no vocabulary in those moments. Nothing could possibly be important enough to throw into the air and take the focus away from the world that was building out right in front of us. I once would buy candy cigarettes and roll them up in my shirt sleeve like Milner, or tee up a song from the soundtrack to match a perfect stretch of road on a long drive. Now, as my dad and I live 200 miles apart and rarely talk, I think back on what joy an organic silence can hold in the wake of a pseudo-estrangement, what it might begin to mean when something that was once a gift is dwindled down to merely a superficial tether between two men who share the same last name.

American Graffiti is tied together by two ongoing (and later connected) throughlines: Curt is searching for a mysterious, blonde-haired woman (Suzanne Somers) driving a white Ford Thunderbird—who he thinks mouthed “I love you” at him at a traffic stop—and radio DJ Wolfman Jack’s nightly show plays continuously in the background of every scene’s film. The Wolfman offers some of the best one-liners in the film, as his off-the-cuff, on-air comedy often wades through the noise of the busy Modesto streets. “Get your bugaloos out, baby! The Wolfman is everywhere,” he yelps at one point. “The secret agent spy-scope, man, that pulls in the moon and the stars and the planets and the satellites and the little bitty space men,” he quips at a pizza joint employee he just crank called.

The fact that American Graffiti even got finished was a miracle, as the film’s shooting was riddled with issues. The team initially wanted to set the story in San Rafael, because Lucas feared that Modesto was no longer the same city it was in 1962—but they had to later settle for Petaluma once the San Rafael city council revoked filming permissions, due to fear of production disrupting local businesses. Lucas found it difficult to get cameras mounted on cars and a crew member was arrested for growing weed, while Le Mat, Ford, and Bo Hopkins are said to have been drunk most nights—which proved problematic, given that the scenes were filmed between 9 PM and 5 AM. The night before Dreyfuss was set to have his close-up shots filmed, Le Mat threw him into a Holiday Inn pool and gashed his forehead. And, most consequentially, two cameramen were almost killed while filming the Paradise Road drag race at the end of the movie.

On the flip-side of near-catastrophe and headache-inducing hurdles, Lucas employed a diegetic approach to the soundtrack, electing to play every song on the streets while actors would run lines on-camera. He and Universal spent so much money on copyright clearances and licensing rights—nearly $90,000 on the featured songs alone—that there was nothing left in the budget for a proper film score. In turn, the scenes where music is absent or muted is reserved for the heavier moments in the screenplay, and it helps better evoke a sense of realness—that, while the radio is always going, you are not always near one. At the scenes during the freshman hop dance, real-life rock band Flash Cadillac & the Continental Kids perform live as Herby and the Heartbeats, adding to that very familiar, cinematic presentation of a local group tapped to cover radio hits for teenagers at functions. Given what we know about Lucas and Star Wars, it’s no surprise that, even on American Graffiti, the director pulled no punches on making the film look, feel, sound and breathe like the period piece it is. And it’s that attention to detail that keeps every scene just as timeless now as it was 50 years ago.

While there are countless moments in American Graffiti that I revisit often—especially the scenes of Toad trying to hawk some booze from a local liquor store, Steve and Laurie slow-dancing to “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” at the freshman hop, and Milner and Carol dousing a car in shaving cream and letting the air out of its tires—I return to one singular sequence more than any other: When Curt finds the city’s local radio station and has a conversation in the studio with (unbeknownst to him) the Wolfman. Still in search of that blonde in the white Thunderbird, he brings a dedication—in hopes that the Wolfman can get it on the air before the sun rises and he can, finally, know who it was who confessed her love to him on the strip. But the scene quickly turns into the Wolfman giving Curt a great piece of life advice, in-between fruitless attempts to get Curt to eat one of the popsicles from the station’s broken ice box.

“I can’t really talk for the Wolfman,” the disc jockey says. “But, I can tell you one thing. If the Wolfman was here, he’d tell you to get your ass in gear. Now, the Wolfman comes in here occasionally, bringing tapes, to check up on me and whatnot. And the places he talks about that he’s been, the things he’s seen. It’s a great, big, beautiful world out there. And here I sit, sucking on popsicles.” When Curt asks him why he doesn’t leave, he offers one solid, finite answer: “I’m not a young man anymore.”

You can draw a lot of comparisons between American Graffiti and The Great Gatsby, particularly in Curt’s journey towards learning who the blonde woman driving the white Thunderbird is and the green light that Gatsby can see from the end of his dock. The green light is a beacon of hope for Gatsby in the pursuit of his longtime love Daisy, while Curt’s desire to connect with Somers’ always elusive character projects his own wavering fear of growing up and leaving town. The Thunderbird sticks out as an outlier car amongst a vast sea of various hot rods and coupes, as does the green, pulsing dot that opposes the lavish, gilded panache that defined the parties at Gatsby’s mansion. Both stories are great renditions of the pursuit of the American Dream done up in different outfits.

While Curt sleeps in his car parked at Burger City, the nearby payphone rings and it’s his white whale on the other line. “You’re the most beautiful, exciting thing I’ve ever seen in my life and I don’t know anything about you,” Curt tells her. She responds not by giving him her name, but by saying she’ll catch him cruising down the strip later that night. Yet, instead of sticking around to see his romantic destiny through, Curt does go to the airport a few hours later, ready to head east and finally start his life—as “Goodnite, Sweetheart, Goodnite” plays softly in the background. At the end of American Graffiti, when he looks out from the window of his plane and sees that white Thunderbird coasting down an empty highway, it’s like that one very thing he was searching for was, once again, just beyond his reach. But, perhaps, he was never truly meant to catch it at all.

I feel that way whenever I watch American Graffiti, that that film’s magic can only exist within the 112 minutes of the movie and it’s not mine to live in. When I was younger, I believed I could, one day, recreate the imagery of a world that George Lucas convinced me would endure somehow, some way. I think about what made my dad share the film with me all those years ago, knowing that the world would actually never look like 1962 California again. I don’t know if it’s profound to ache for the past in a near-fairytale place like he and I have, or if it’s just plain human. I guess, sometimes, those two things simply end up the same. I’ve never asked him what it is about American Graffiti that makes him rewatch it year after year. Perhaps it’s to scale back the miles in which our own pasts can migrate, but I’m sure he loves it for the cars and the music and the way he can turn his brain off and just enjoy the film for the sake of spending a few hours immersed in a good-looking picture.

But I cannot do the same, unfortunately. 50 years later, and the magic has worn off—not because the film is no longer great (it very much is still a perfect movie that I love and rewatch constantly), but because I have lived through far too many regrets and far too much loss to bottle up joy just for the sake of being entertained. Nostalgia is a deathly curse that we all must bear. Maybe, at one point, it was easy to capture the good and fun parts of the movie for the sake of not taking things so seriously. But I’m much older than the characters in American Graffiti were when the film takes place and I haven’t got it all figured out yet. In fact, it’s pretty heavy labor just trying to get to the next day in this timeline. After spending two years inside and, even today, living below the poverty line, I’m still searching for my blonde in a white Thunderbird. Maybe you are, too.

Matt Mitchell reports as Paste‘s music editor from his home in Columbus, Ohio.