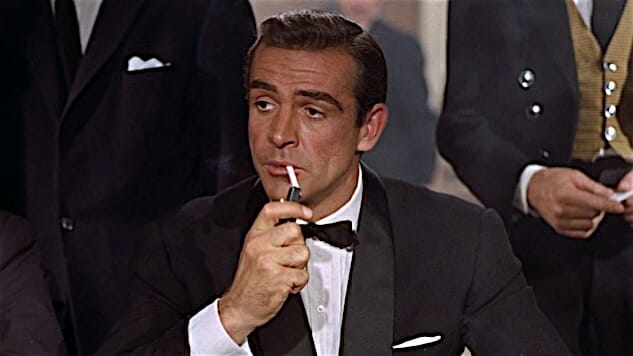

Who Is James Bond?

Idris Elba casting rumors call into question just how to fix 007.

“The two survivors. This is what she made us.” – Silva

For about the eleventieth time since 2012’s Skyfall, rumors have swirled that Idris Elba might be considered for the role of 007, though, as of this writing, they have again (per The Hollywood Reporter) been debunked. It’s just as well that they have been. Elba has never officially expressed any real enthusiasm for the role, for one thing. For another, I personally don’t want a gifted actor like Elba stepping into a franchise that doesn’t seem like it knows what it’s doing, or who its central character actually is.

“You see, when your intervention forced me to present the world with a new face, I chose to model the disgusting Gustav Graves on you.” —Colonel Moon

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-