How Jennifer Lopez Became a Megastar Celebrity and an Underrated Actress

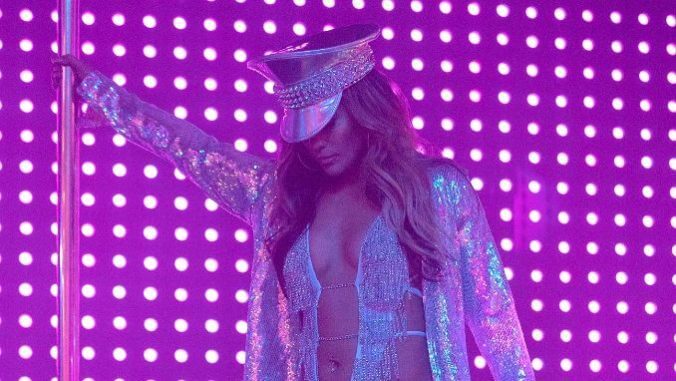

At a time when the concept of the A-Lister has dramatically changed and Hollywood is less concerned with creating new icons, it’s notable how Jennifer Lopez has remained an undisputed megastar for close to three decades. She’s instantly recognizable to the world: J.Lo, the indomitable celebrity who has conquered music, film, TV, fashion and every tabloid on the planet. In recent years, she’s experienced a resurgence of sorts, a minor renaissance thanks to the critical success of Hustlers, a co-headlining gig at the Super Bowl Halftime Show, and the eager revival of Bennifer. It seems like she’s never been more beloved, or taken more seriously by those who previously doubted her. She’s bounding into the action genre now with Netflix’s The Mother, a reminder that she’s that rare celebrity who is willing to try almost everything. Of course she’s a star, but that ambitious climb to the top came with a curious side effect. It made her a criminally underrated actress.

In the early ’90s, Lopez, fresh off her tenure as a Fly Girl on In Living Color, landed a few supporting gigs in quickly canceled TV shows before stepping onto the big screen. It didn’t take long for her to find a starring part in a Francis Ford Coppola film. Unfortunately, it was Jack. The real meat of her acting career came the year after that execrable schmaltz-fest’s flop release, in 1997. That year, Lopez had three major roles that revealed her to be a blossoming character actress with leading lady potential: U Turn, Blood and Wine, and Selena.

As a young Latina actress in an industry dominated by whiteness, Lopez was often put in unenviable positions during the beginnings of her acting career. Even in good roles, she had to face the racist mess of a business that saw all women of color as interchangeable. In U Turn, a deeply twisted black comedy from Oliver Stone, she is cast as a half Native American woman, while in the underrated sun-drenched noir Blood and Wine, she’s Cuban (Lopez is a New Yorker with Puerto Rican parents.) In these particular films, the male directors focus heavily on her sexuality, exoticizing her from a mere femme fatale into something more sinisterly Other. One can hardly blame her for, post-movie-star glow, choosing to be a rom-com headliner where her identity is not considered a hindrance to basic storytelling cues.

Yet her work in these films is strong, for Lopez has always possessed a unique charisma that seems primed for cinematic glory. She’s impossible to look away from, inhabiting the screen as though it was her absolute right to do so. In U Turn, which was dismissed by critics at the time for being luridly nihilistic, she plays a woman trapped in an incestuous relationship with her father. When an overtly harried Sean Penn rolls in, stuck with no chance of escaping a hellish Arizona town, she latches onto him immediately in the hopes that he will kill her father/husband for the insurance money. The character evokes Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, the queen of the femme fatales who always seems two steps ahead of every hot-headed guy in the room. Lopez, who looks super young here, is as good at calculated manipulation as she is at displays of stunted naivety. Is she a victim? A manipulator? Does it even matter, especially when the ensemble is stacked to the gunnels with violent scumbags? If everyone plays dirty, you go dirtier, and that sly caustic edge to Lopez’s performance hammers that home.

It’s a skill that also shines in Blood and Wine, where she has believable sexual chemistry with Jack Nicholson as his maid girlfriend who helps him to pull off a ramshackle heist. As Gabriela, she truly loves Nicholson’s Alex, a failing wine merchant who needs to steal diamonds from his mistress’s employer to stave off the debt collectors. Bob Rafelson’s film is vintage noir, so acerbic and cynical about humanity that it seems constantly at odds with the burning sunshine and picturesque locales of Miami. Gabriela’s genuine affection for Alex, a man who certainly doesn’t deserve it, is a sliver of light in this pitch-black narrative. For Lopez, it’s a chance, albeit in a relatively underdeveloped role, to show her mettle as a figure of integrity surrounded by losers and scammers. Of course, both Blood and Wine and U Turn were stepping stones to perhaps her best film role, and her strongest display of noir prowess, Steven Soderbergh’s Out of Sight. During this period, it felt like Lopez could have chemistry with absolutely everything, so it was no wonder she seemed primed to be a major actress.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-