Beirut’s Zach Condon Escapes Himself

We caught up with Condon about the release of his first new album in five years, Hadsel.

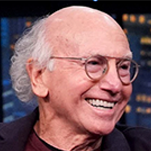

Photo by Lina Gaißer

Hadsel is a small town way up in the northern part of Norway with a population of just over 8,000—a place where vast, snow-tipped mountains are reflected in calm, slate-black waters. It’s just the kind of setting you might expect Zach Condon to write a song about: idyllic, secluded and timeless. As the songwriter and frontman of Beirut, Condon has embraced his acute sense of wanderlust since the beginning, writing songs with names like “Prenzlauerberg”, “Bratislava” and “Postcards From Italy” long before leaving his small suburban town outside of Sante Fe, New Mexico. He’s traveled the world several times over in the 15 years since, making the dreams of a precocious creative teenager a reality.

And yet, when Condon made the northern trek to Hadsel in the first days of 2020, it wasn’t so much a destination as it was an escape. 2019 had nearly destroyed him. “Zach has been advised not to sing on tour,” read the band’s statement upon the cancellation of the remainder of their 2019 shows. Condon was spent, an accumulation of years of issues—both physical and mental—having finally taken their toll. A singer told not to sing might sound like a particularly harsh sentence but, for Condon, his prison had been building brick-by-brick for years. “Acute laryngitis” might have been the official diagnosis, but it seems clear now that his ailments were far further-reaching. The waning days of 2019 might have left Condon in a “state of severe shock and self-doubt,” but 2020 offered an escape. And he found it, as he so often does, behind an instrument in the furthest corner of the world.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-