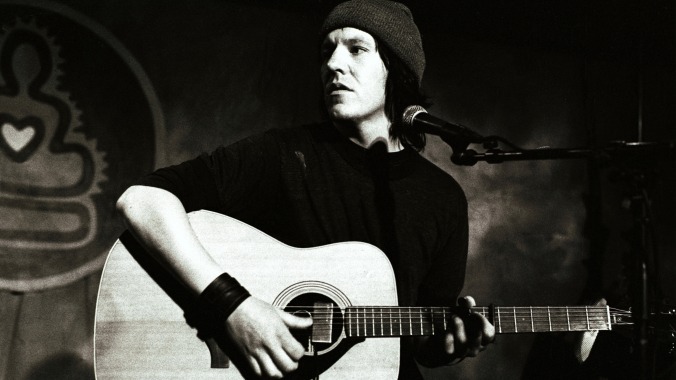

Somewhere in this sentiment, I believe, is the gist of Elliott Smith and what sets him apart from what his legacy has twisted itself into. The concept of influence is a difficult one to grapple with, especially as I tend to not believe in artists shaping how they’re remembered outside of simply creating their work and letting the public absorb it how they will. The thing is, I would feel comfortable making the statement that no one’s influence can be felt as strongly in indie music today as Elliott Smith’s can. Yet, with someone so distinctive and still omnipresent—whose fingerprints you can decipher within the first 10 seconds of a given song by someone else—I sometimes fear we’re flattening him into something he’s not to make him easier to categorize or digest. Even before he passed away, people spoke about him as if he existed in a two-dimensional shape, draining his preternatural talent for songcraft and production of all vibrancy, falsely sticking him under the umbrella of “sad guy with a guitar”—the ultimate version of a person “trying to get everybody to feel just like them.”

Even the people who knew he was special treated him like he’d already exited the building, behaving less like he was a person and more like he was a vessel for their own truth he’d tapped into. When you watch fuzzy VHS footage of people howling requests and proclamations of love at the man, you get the feeling they’ve already martyred and buried him, even if that wasn’t their intention. Smith’s own personal battles are probably (unfairly) the most documented thing about him, but I’d imagine those two extreme reactions from others would be difficult for any person to deal with. For such a natural musician who traversed everything from lush Beatlesque pop to harrowing, noisy guitar-rock in the span of a few years, I can understand how limiting it might have felt. It’s strange, because I’ve never listened to Elliott Smith and thought he was telling anyone how to feel. If anything, he was working to realistically capture what he saw and felt. He let you fill in the blanks, but I guess he couldn’t help if people filled them in with just as much intensity.

To be honest, the emotion I’ve always felt most potently in his work is anger. Obviously, that’s only a half-step away from sadness on the emotional flow chart, but there’s a clear strain of resentment—aimed at himself, at those who tried to hurt him, at those who tried to help him, for a world that doesn’t know how to help him after a certain point. There’s beauty in it too, but this doesn’t seem to have translated to the average listener when you watch interviewers badgering their stilted interviewee once he’s thrust into the public eye—forced to play live and do interviews in a trade-off to be able to write and record, as Smith’s friend and collaborator Larry Crane says he had expressed to him in the 2014 documentary Heaven Adores You.

The other crucial mistake is to make the assumption that all writing is entirely autobiographical, as if one can only observe and empathetically portray things if they’re from experience. The most comfortable I’ve ever heard Elliott Smith sound speaking in an interview is with Barney Hoskyns in 1998, shortly after his famous performance of Good Will Hunting’s “Miss Misery” at the Oscars. “I’m definitely in [the characters in the songs], but on the other hand, it’s not like a diary or anything,” he told Hoskyns. “People seem so chaotic internally, but being filtered through some form, like making a record, sort of filters it down into something that can be understood. It’s hard to represent chaos or an absence of something. It’s much easier to represent the presence of something or a situation. People can be chaos, but it’s hard to fit it into some creative piece that you made.”

Perhaps, then, the true hallmark of Smith’s writing is that he remained faithful to documenting human chaos—whether it was his own or if he decided to funnel his imagined version of characters’ lives into tales of grief, fury and quiet beauty, all in three minutes’ time. Perhaps that’s what makes him so frighteningly tangible, what makes the devoted so attached. It’s more like creating an impressionistic dream more legible than it is writing in a traditional folk mold. His lyrical specificity rang true because the universal could be gleaned from it. For better or worse, biography will inform what we hear, but knowing him wasn’t the point. I don’t think he ever wanted it to be.

The beats of Elliott Smith’s brief life story are almost hallowed music legend now, but are worth summarizing in order to capture the lead-up to his solo debut album: Smith, aged 14, moved to Portland, Oregon to live with his father after primarily growing up with his mother and stepfather (Bunny and Charlie, two of the real people from his life to frequently show up as characters in his songs) outside of Dallas. He formed the band Heatmiser with his friend Neil Gust while studying at Hampshire College, eventually becoming well-known in Portland’s thriving indie scene.

“I didn’t like how I sounded singing in my band,” he told Hoskyns later on, “but it was hard to sing like how I wanted to because playing live, I had to just be at the top of my lungs all the time and it made me sound like I had a really bad cold or something. It sounds really hoarse and macho and weird. I just didn’t think other people would like it, so I didn’t play it for them. But eventually, I got over that, which I’m happy that I did.”

Wanting to venture outside the heavier sonic palette of Heatmiser, Smith continued to harness his writing chops with songs that didn’t belong to any specific project. Having already released Heatmiser’s debut album Dead Air the year prior, late 1993 saw Smith record his latest batch of nine in-between songs on a four-track machine that belonged to the roommate of his girlfriend, photographer and Heatmiser’s then-manager J.J. Gonson. Gonson played the tape—recorded and played entirely by Smith in her basement—to local Portland label Cavity Search, who requested to release the entire thing as-is, much to Smith’s dismay. Once he’d been convinced, he chose one of Gonson’s pictures of his bandmate Neil Gust and their friend Amy Dalsimer for the cover and named the newly-minted “album” after the first track on the tape: “Roman Candle.”

30 years on, I don’t think it’s radical to hold the opinion that Roman Candle, while great, is the “worst” of Smith’s six albums. It’s certainly the least fleshed out for obvious reasons, given the background of its recording. It’s redeemed by the fact that the songs are strong, even in their skeletal form, as Cavity Search clearly heard. The spareness is a matter of necessity, but you can tell it can bear the weight of dense arrangements—showcasing Smith’s often overlooked technical playing abilities. The only reason we might underrate it now is that we can look to what this seed of insane talent will build to, though the first record introduces thematic concerns and a penchant for melodic complexity that will show up again in subsequent records.

Roman Candle, thematically, is all about halves—half-riddles, Irish goodbyes, phone calls where no one says what they really want to say and pleas to not talk about it. Even before his own drug use started, Elliott Smith always focused on dependence, capturing people drifting apart or coming back to things they depend on. I’m sure that reliance strikes further fury into the hearts of those who experience it, leaving them unsure where to turn. There’s an intimacy to the album simply because of the way it was recorded, but this would prove to be a factor that allowed fans to feel as if they knew Smith as it remained his signature delivery style down the line. Even as Figure 8’s full-band forays allowed him to widen the scope of his musical ambitions, it still sounds like he’s singing right next to you—voice double-tracked and fragile, even when it’s telling you off.

The title track feels like an almost archetypical Elliott Smith song—a precursor to a song like “Southern Belle” on the following record, both in terms of the intricate guitar work and the subject matter of an abusive man, most likely fueled by his relationship with his stepfather. It already contains the aggression and eerie intensity that betrays how close the music sounds to its listener, leaving them to exist inside the narrator’s rage: “I want to hurt him / I want to give him pain / I’m a roman candle / My head is full of flames.” “No Name #4” tackles a similar subject, laying out the story of a woman trying to escape a dangerous situation before tacking something as staggeringly conversational as “And you look scared / It’s our secret, do not tell, okay? / Let’s just not talk about it,” onto the end.

“Condor Ave” is maybe the clearest example of Smith’s short story impulses, neatly presenting plot points and description of a woman who storms out after a fight with her significant other, only to fall asleep behind the wheel after she drives away and hits a homeless man, killing them both. His more purely fictional lens brings out some of his most poetic lines, but the final verse pivots to what seems to be the now-dead woman’s perspective, shifting the tone and language completely: “What a shitty thing to say, did you really mean it? / You never said a word to me about what passed between us / Now I’m leaving you alone, you can do whatever the hell you want to.”

These sharp moments where Smith’s personality as a writer shine through work in contrast to something like the nocturnal, Samuel Beckett Watt-inspired “No Name #3” (the album’s most well-known song, likely because of its use as the one pre-existing, non-Either/Or song in Good Will Hunting), which lopes alongside what reads as a disgruntled couple shaking off a fight that took place earlier in the evening. The hazier tracks, fit to stagger home to, feel digestible compared to the more actively frightening work Smith would create later—especially compared to the booming, White Album-esque hallucinations brought to life on the posthumously-released From a Basement on the Hill—and still holds the listener at a slight distance as he figures out how to write outside of his thrashing post-punk enclosure.

This, perhaps, is what makes the penultimate track “Last Call” stand apart. It certainly sounds like it exists in tandem with Heatmiser, featuring the only electric instruments on the album. Still, lyrically and in terms of delivery, it feels like one of the first instances where we see Elliott Smith really aim to wound. Where those little conversational turns just felt like reality checks in largely straightforward songs, “Last Call” scratches and claws in its pointed frustration: “Last call, he was sick of it all / The endless stream of reminders / Made him so sick of you, sick of you, sick of you / Sick of your sound, sick of you coming around.” That repeated swirl of “sick of you” feels particularly intentional, squared perfectly with both the melody and the sentiment. By the time Smith is begging for his maker to “never wake” him at the end, it recalls another thematic staple he’ll return to in years to come: self-loathing as reaction to the ugliness of the song’s situation, of the world he’s reflecting back to us. Even compared to the violent proclamation of “Roman Candle,” “Last Call” seethes with a hatred that we’ll hear again—though this might stand as the most unfiltered version of the emotion we hear.

Maybe it’s some cosmic trick where the universe knows about Elliott Smith’s affection for writing in bars, but I feel like he always follows me there—the saint of New York dive bars, out to haunt me in the beer-soaked wooden booths even if he’s left them behind. For his relatively brief spell living in New York, he wrote songs for what would become 1998’s XO at Luna Lounge—which closed in 2005 and is now built up into a boutique hotel—but I still feel he sneaks up on me in similar places. One time, a bartender at another Lower East Side haunt I adore—quite literally only a block-and-a-half from where Luna Lounge once stood—wore a jacket with the “Last Call” lyrics “YOU’RE A CRISIS YOU’RE AN ICICLE” painted on the back, as if they were the rousing chorus of a punk anthem that had to be enshrined in leather.

My brain couldn’t help but finish with “You’re a tongueless talker, you don’t care what you say / You’re a jaywalker and you just, just walk away / And that’s all you do,” and in that moment, I didn’t think there had ever been anything more damning ever written. It’s a perfect distillation of Elliott, the songwriter. Plenty of guys with guitars came up in the indie wave of my teenage years, playing to shitty boys smoking in lazy, weightless sunlight you could hear, but I couldn’t imagine ever comparing one of them to Elliott Smith. The jaywalker strolls aimlessly and confronts nothing, says nothing. Everything has its place, but these songs never stray from their target. There’s a reason he still disarms listeners like he does, precise and acidic in his effort to stop the sting he feels himself.

Another time, I heard “Wouldn’t Mama Be Proud” from Figure 8—Smith’s biting ode to his experience on a major label—walking to another bar to meet a friend. When he got to the line “If I call to keep it together like you say you know I can do,” it occurred to me that I’ve never been able to tell whether he’s saying “can” or “can’t” there. The lyrics are printed on the physical copies of the album I’ve owned over the years, but I still don’t feel in my heart of hearts that I can trust it. My own answer shifts depending on the day I listen, which feels pertinent to me somehow. Does it change the meaning of the song? Is this other person he sings to’s opinion on whether he can or can’t make it the whole point? Is the “you” referring to the listener, the person who arguably binds him into these constrictive professional situations? How should we take that, now that we know how his life tragically ends? Is it a challenge? Is it a plea for us to leave him alone? I got to my destination still feeling the question prodding at me.

Most recently, I sat in a dive near Washington Square Park where the walls are decorated in bottle cap art and happy hour is still cheap despite the surrounding area’s new, unsuitably shiny exterior. I sat by myself reading when “Waltz #2m (XO),” easily Smith’s most famous song to allude to his relationship with his mother, started blasting into the large, empty space, and I felt I had no choice but to put my book down and mouth all the words to no one but myself. I thought about my own mom playing me this very song in her old car when I was young, and how that was probably the first time I had ever heard his music. She’s always been an avid music follower and had been an Elliott Smith fan in real time. I’ll still come upon incredible sets he did in town while she still lived here and I think about asking her why she didn’t go—like his show at the old Knitting Factory on New Year’s Eve of 1999 (and then, after a champagne toast with the crowd, into New Year’s Day of 2000), where he closed with “Last Call” at an audience member’s request—but then I remember she was probably taking care of me instead of getting her hand stamped to sit hushed and awed in Elliott Smith’s presence. This simply has to be the order of parental priorities, I suppose.

A few years ago, she read a biography about him, and the only thing I can recall her saying about the book was “You know, he was so smart,” delivered emphatically. I think she was referring to how effortless the musical side of it was for him, how involved he was in the production and arranging process—the craft and complexity baked into it all. Still, as someone who grew up around other adults who were largely insensitive when they spoke about those who struggled with mental illness or had chosen suicide as their way out, probably due to a lack of education or experience with it themselves, I’ll always remember that my mother, who still loves Elliott Smith to this day, didn’t choose the word “weak.” She chose “smart.” I really hope he knew that about himself, too. I never want those of us who still love his work to forget how masterful it is in the online circle-jerk of pithy punchlines about how sad he sounds, how sad he makes us. I still feel he deserves more than that.

The genesis of this all comes accidentally, with Roman Candle born in a basement on a four-track tape under the assumption that no one would hear it—until everyone under Elliott’s later material’s spell ventured back to the CD racks to seek it out. “When they wanted to put out my record, I was totally shocked,” Smith told Under The Radar about his first record in his final major interview. “I thought my head would be chopped off immediately when it came out because at the time it was so opposite to the grunge thing that was popular.” He knew that his own work contained that same grit, the same disaffection as the rock du jour, but seemed aware that it would take time for that to click—sitting and answering the same unresearched questions until he wouldn’t let anyone ask him questions anymore.

It’s painful to go back and look at these filmed interviews now, most of which ask some version of “Why are you so sad?”—which Elliott Smith evidently decided didn’t deserve a dignified answer, so he repeatedly avoided giving one. If Smith’s music was his method of taking something dreamed or incomprehensible and molding that into a tangible body of work, then there will always be people returning to him as they search for someone to voice their own ruthless joys and fears.

For all the times where he slid into self-deprecation in his writing, I return to XO’s “Tomorrow Tomorrow” and think about that tricky concept of legacy a lot. I wouldn’t dare assume the song was meant to be personal or to dream up Elliott Smith’s intention for you now, but maybe, when I was younger, I’d always hoped he’d written it as an olive branch to that creative side of himself—the side he felt he could rely on to make all human chaos worthwhile. When he sings “They took your life apart and called your failures art,” he doesn’t end the line with the jokes others will tell, the box which record labels and press will force him into or the morbid mythology trumping a generation-best body of work—where a death colors the artist’s vision against their will, allowing others to romanticize that which was painfully real for both the artist in question and his still-living loved ones.

Instead, he sings: “They were wrong, though.” I hope that, wherever he is now, he still believes that. I know I do.