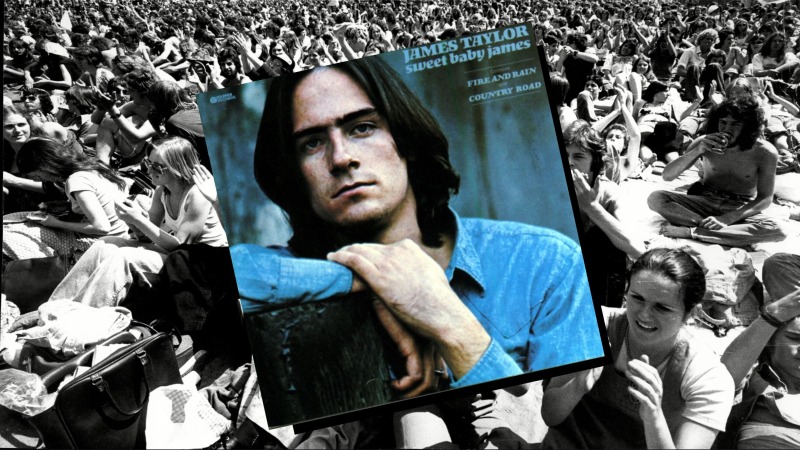

Time Capsule: James Taylor, Sweet Baby James

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at James Taylor's breakthrough album Sweet Baby James, which is by now a stone-cold folk-rock classic.

When I hear James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James, I think of my mother, who’s been playing the album in our house since I could form memories. But for my mother, it’ll always remind her of her father; my grandfather gave her Taylor’s sophomore record when he returned from Vietnam and the family relocated across the country. My mom was in middle school—a difficult time no matter what, but especially considering they’d moved from the West Coast to Pennsylvania, where she struggled to make friends. As a lonely tween, she’d listen to the album on repeat, thinking especially of her dad and everything he experienced in Vietnam when “Fire and Rain” came on: “I’ve seen fire and I’ve seen rain / I’ve seen sunny days that I thought would never end / I’ve seen lonely times when I could not find a friend / But I always thought that I’d see you again.” I’ve often thought of my mom at 12 and wished I could give her a hug, some comfort, and let her know that she’s one of the best people to have ever walked the planet. But she didn’t need a time-traveling daughter to tell her that, because James Taylor was there to soothe her aching heart with his exquisitely gentle songs.

By the time Taylor released his second album in 1970, just shy of his 22nd birthday, he had befriended the Beatles, survived heroin addiction (an ongoing battle for him), been in a motorcycle accident that broke his hands and feet, and underwent treatment for depression and suicidal ideation. He’d been to the other side and back, and would do so again and again in his life. You can hear that resilience in his warm voice—that sense that he knows how bone-crushingly hard our time on earth can be, and yet endeavors to continue on in spite of it all. As Taylor told Paul Zollo in an excellent 2007 interview, “My instinct is to humor and to ecstasy and to bliss.” I detest the idea that an artist has to have suffered to create work of merit; what I will say is that his music connects on a deeper level because of what he experienced. His manager and Sweet Baby James producer Peter Asher put it best (as per Ian Halperin’s biography Fire and Rain: The James Taylor Story): “James had been through so much by the time he was twenty… James was already singing with the conviction of a singer much older than himself. Everything that he had already been through was evident in his songwriting.”

Sweet Baby James was truly Taylor’s breakthrough to the mainstream; his self-titled debut album received critical praise, but didn’t perform well commercially, in part because Taylor was receiving treatment at a psychiatric facility and couldn’t promote the album. But now, with Warner Bros. Records behind him, Sweet Baby James was destined to become a folk-rock classic. Perhaps it didn’t feel that way for Taylor at the time—he was couch-hopping between Asher’s place, session guitarist Danny Kortchmar’s home and anywhere else people would let him stay. In fact, he cheekily named the final song—the last one needed to meet the label’s minimum length—“Suite for 20 G,” as they’d been promised $20,000 upon the album’s completion.

But let’s return to the very beginning: Sweet Baby James kicks off with the title track, which at first follows a lonely cowboy who dreams of “women and glasses of beer,” before turning to the frost-covered Berkshires, where Taylor underwent treatment in 1968. Taylor wrote this lullaby on the long car ride down to North Carolina to visit his newborn nephew, the titular “Sweet Baby James” who was named after him. Sleepy steel guitar wavers in, like the cowboy’s visions of “moonlight ladies” swirling in his head. Taylor’s cowboy is unlike the stalwart, stoic John Waynes of the world—instead, he invites a wistful softness into the lonesome man’s existence “on the range.” His allusions to his hospitalization here and throughout the album show that Taylor was ahead of his time in terms of discussing addiction and the reality of depression—something which can lie dormant, but never quite leaves you. While the line “ten miles behind me and ten thousand more to go” refers to the road trip he took to visit baby James, it could also be interpreted as the winding path to recovery. The sweet, bucolic imagery here was designed to soothe, but its layers run deeper for the attentive listener. In fact, that holds true for most of the album; on first listen his music has a radiant ease to it, but that belies the hard-won lessons it imparts.

The folksy lullaby of “Sweet Baby James” is followed by Taylor’s bluesy hymn “Lo and Behold.” The motif of dreams returns here: “Deep in the night, down in my dreams / Glorious sight this soul has seen” he sings, echoing the line from the opening track, “Won’t you let me go down in my dreams?” The song is rife with Christian imagery (“You just can’t kill for Jesus” and “Don’t build no heathen temples / Where the Lord has done laid his hand now”), but in a 1973 Rolling Stone interview he clarified that he’s “religious, but that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the church.” In that interview with Zollo, Taylor describes his approach to life’s bigger questions as “agnostic spiritualism,” calling for us to “[surrender] control and human consciousness.” He draws upon the religion on “Country Road,” too (“Sail on home to Jesus won’t you good girls and boys,” as well as a line referencing the Black spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”), approaching the Bible as a literary text to make allusions to more than a strict guide by which to lead life.

“Sunny Skies” shows off the ironic side of Taylor’s songwriting, as he shares over summery acoustic guitar and light percussion what life is like in the midst of depression: “He closes his weary eyes upon the day / And throws it all away.” The next track, the big and brassy “Steamroller,” parodies the rich white kids he met who ripped off Black blues musicians, while also skewering toxic masculinity. Taylor hilariously compares himself to a steamroller, a cement mixer, a demolition derby and a napalm bomb throughout a track in which the narrator tries to win a woman’s affections, cartoonishly highlighting how much of the language men use around sex involves annihilation. Once again, Taylor proves refreshingly ahead of the times.

“Country Road” is an exemplar of one of Taylor’s favorite types of tunes: highway songs that lean into a restless wanderlust. The notion of life being about the journey, not the destination can feel rather cliched, but when Taylor sings effortlessly of how “my feet know where they want me to go / walkin’ on a country road,” the idea feels fresh again.

In an album brimming with masterful songwriting, “Fire and Rain” remains a cut above the rest. The track was written in honor of Taylor’s friend Suzanne Schnerr, who died by suicide. Guitar and piano weave together sublimely, providing the scaffolding for Taylor’s heartbreaking lyrics. Anyone who’s felt at the end of their tether can find solace here, knowing they’re not the only ones who have struggled to go on: “Won’t you look down upon me, Jesus? You’ve got to help me make a stand / You’ve just got to see me through another day.” Big, booming drums leading up to the third verse provide the perfect amount of emphasis—a satisfying catharsis that doesn’t overdo it. My heart always aches on the final version of the chorus, when Taylor’s voice careens higher, bringing extra bittersweetness to the line, “I’ve seen lonely times when I could not find a friend.” Whatever you are going through, the song is there to accompany you, assure you that you can survive life’s fire and rain.

James Taylor has always been a part of my life and always will be. His version of “Getting to Know You” soundtracked my sister’s in memoriam video. For a while, my mother had a framed photo of him in our house, and a new friend mistakenly thought it was a picture of our dad. Just this past Christmas, my brother-in-law and I pooled our money so my parents could see Taylor play this year. Even if younger generations only know James Taylor as Taylor Swift’s namesake, that will never erase the impact of Sweet Baby James on confessional singer-songwriters everywhere and—more importantly—the lonely and downtrodden who need his words of wisdom.

Clare Martin is a cemetery enthusiast and Paste’s associate music editor.