Mdou Moctar’s Songs of Protest and Celebration

The Nigerien quartet’s latest album, Funeral for Justice, is a ferocious denouncement of colonialism and a tribute to the enduring Tuareg culture.

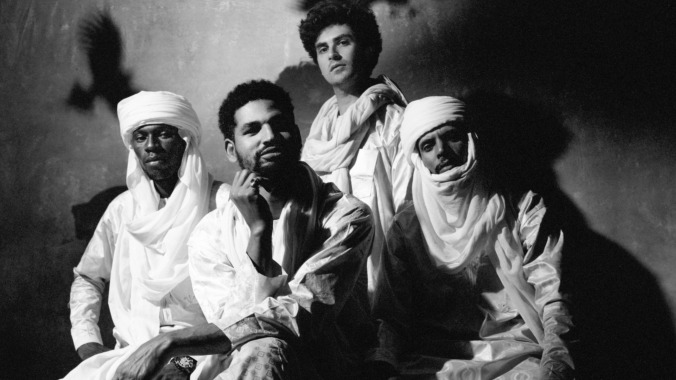

Photo by Ebru Yildiz Music Features Mdou Moctar

Mdou Moctar uses his guitar to emulate the sound of a siren. During the recording sessions for Funeral for Justice, his band’s latest album, Moctar inched his hand toward the high edge of his lefty fretboard, using his preferred picking hand to instead conjure a burst of wailing noise. Once they wrapped up tracking it, producer and bassist Mikey Coltun was talking to Moctar about why he did that and what he was feeling in that moment. “This is a cry for help,” the guitarist and vocalist told his bandmate. “This is the sound of the siren.”

The Tuareg musician and bandleader plays the six-stringed instrument like it’s the co-vocalist alongside him. “Guitar is everything for me,” Moctar explains from the Matador Records office in Lower Manhattan via Zoom. “It’s my key to everything.” Most of the lyrics for Funeral for Justice are sung in his native tongue, Tamasheq, but the messaging of the record rings clear despite any potential language barriers and Mdou Moctar’s growing audience in English-speaking countries. Stacked with countless incandescent guitar solos that erupt like fireworks, there’s an underlying urgency to these songs. The guitar may as well be another one of Moctar’s native languages. It’s a vehicle for his convictions.

Funeral for Justice is a roughly 40-minute call to arms with a stalwart anti-colonialist stance. Three of the band’s four members—Moctar, drummer Souleymane Ibrahim and rhythm guitarist Ahmoudou Madassane—are from Niger, a landlocked country in West Africa. Ibrahim and Madassane live in Agadez, and Moctar lives in a remote village in the Saharan Desert. The band’s Nigerien roots mean they are well-acquainted with the insidious colonialism that has spread throughout their home country like a plague. France is a notorious colonial power, and it only recently ceded all of its Nigerien military bases because of a military coup last year. Because of the coup, Moctar and his band were forced to stay in the United States after finishing a North American tour. “I didn’t know what was going to happen,” he recalls. “I was just thinking about my family and how my family would survive. It was a difficult time.”

Although Mdou Moctar wrapped up the recording process of Funeral for Justice in 2022, there’s an added layer of depth to the geopolitical protestations that resound throughout the new album. It may not have been directly informed by it, but it’s evidence of the real threat of colonial occupation, a threat that Mdou Moctar rails against in their music. He clarifies that he doesn’t support the violence of the coup itself, but he acknowledges that it’s a consequence of the French imperialism that afflicted Niger as early as the 1890s. “The coup is not a good way to support the people, so I never supported it,” he says. “At the same time, I never liked France or their colonization. I never liked their system.”

Mdou Moctar’s new record is a celebration of Tuareg culture and, simultaneously, a denunciation of France’s exploitation and profit from Niger’s uranium reserves. “Sousoume Tamacheq” explores the French language’s permeation throughout Niger and how it has slowly replaced Tamasheq. It’s a searing manifesto aimed at fellow Nigeriens to preserve the native language and, by extension, its culture. “Oh France,” the penultimate cut from Funeral for Justice, is an incendiary condemnation of its titular country’s “lethal games” and “turbulent relation.” The opening title-track is both a lamentation and a demand for justice. “We feel like justice doesn’t exist,” Moctar says of choosing the album’s name. “Even the way that the record starts, with me calling out to [world] leaders, it’s a very direct and very urgent record with the music following the message.”

That much is apparent from “Funeral for Justice” alone. Punctuated by boisterous cymbal crashes and Moctar’s signature shredding, it’s an undeniable rallying cry. Much like feminist activist Carol Hanisch argued in her influential 1970 essay “The Personal Is Political,” it’s impossible to separate the politics from Mdou Moctar’s music. They are one and the same. “What is going around the world, that is the reason for this album,” he says. Even though the band doesn’t have much faith in global leaders, there is a strong sense of trust among themselves. In the time since their 2021 breakthrough record and first for Matador, Afrique Victime, that trust that all four members have for one another has only hardened. “That’s a big theme on this record,” Mikey Coltun says. “These are songs about the trust we have or don’t have with African leaders or the rest of the world of colonization. But there is trust between us.”

Differentiating Funeral for Justice from its predecessor, Coltun believes there is a more intrinsic “live-band” feel on this one. “Afrique Victime felt like the ‘guitar hero’ record, and Funeral for Justice feels like the ‘band record,’” he explains. While there’s still plenty of guitar heroics to be had on these new songs, it’s easy to see what Coltun means about this record sounding like more of an all-around, banded effort. Take a song like early highlight “Imouhar,” where Ibrahim begins playing his two-three drum pattern even faster at the midway point, and the other three musicians follow suit. The naturally fluctuating tempos all over the LP signify the overarching theme of tacit understanding. All four musicians operate like a single organism, moving in tandem and taking nonverbal cues like jazz performers.

“There is a trust that Mdou can play whatever he wants, and we’re there; the band is there to support, and we all move as a unit,” Coltun says. Funeral for Justice is the product of several jam sessions they recorded at a rented house over five days in New York State’s Catskill Mountains. Coltun used a handful of drum mics to record the band and used direct-input for the rest, so the band could play everything live. He would later stitch various parts together and edit the performances; it was a way to intentionally recreate the sound of their raucous, freewheeling and setlist-free live shows. “Even though the songs are about these very important, hard subject matters, it’s still a party,” Coltun says. “It’s still a celebration.”

After accruing a larger audience with Afrique Victime, Mdou Moctar knows there are more eyes and ears on them. With Funeral for Justice, their platform has gotten even bigger. “We like the intimacy of a small room, but as we’re growing and playing bigger venues and bigger festivals, we can reach more people,” Coltun says. “This is the first Mdou Moctar record that feels closest to the live show, which is such a sacred, special thing.” As the group embarks on a U.S. tour in support of Funeral for Justice, these shows won’t feel like funerals as much as celebrations, each night a lively tribute to the Tuareg people. Every night, Mdou Moctar will call for justice with a communal gathering, rife with scorching guitar solos. It’s not a burial; it’s a resurrection.

Grant Sharples is a writer, journalist and critic. He writes the Best New Indie column at UPROXX. His work has also appeared in Interview, Pitchfork, Stereogum, The Ringer, Los Angeles Review of Books and other publications. He lives in Kansas City.