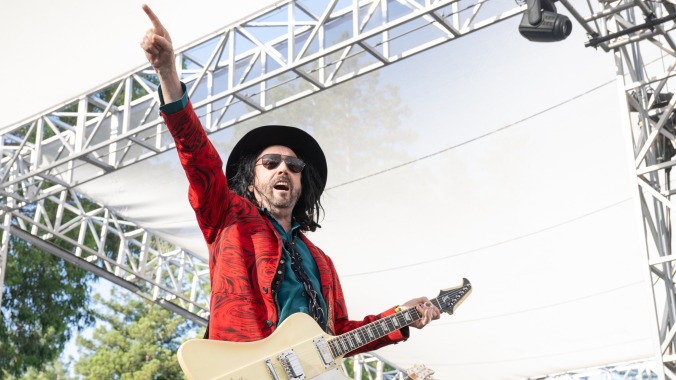

One of rock ‘n’ roll’s greatest journeymen, Mike Campbell has been around the block a time or two. The Panama City-born guitarist came to prominence as the zag to Tom Petty’s zig, having co-written some of the best rock songs of the last 50 years (“Refugee,” “You Got Lucky” and “Runnin’ Down a Dream,” to name just a few). He played on some Don Henley hits in the 1980s, is credited on nearly every Stevie Nicks solo record and, in 2018, briefly replaced Lindsey Buckingham in Fleetwood Mac. But while still playing with the Heartbreakers more than 20 years ago, Campbell formed a band called the Dirty Knobs with Jason Sinay, Matt Laug and Lance Morrison. They’d hone their Zeppelin and Kinks influences and play at bars around the country in-between Heartbreakers tours. Sinay would leave the band in 2022 to focus on solo material and his replacement, Chris Holt (also a Henley collaborator), has stepped in masterfully since.

After Petty passed away unexpectedly on October 2nd, 2017 and the Heartbreakers hung up their instruments—and after Campbell had that stint in the Mac—Campbell has been on quite a tear with the Dirty Knobs (all while still grieving his best friend’s death). They released their first album, Wreckless Abandon, in 2020 and followed it up with External Combustion two years later. As Laug was preparing to begin a tenure as the touring drummer for AC/DC, he helped Campbell and the Knobs cut their newest record, Vagabonds, Virgins & Misfits, before high-tailing out of there. Former Heartbreakers drummer Steve Ferrone was brought in as his replacement, making for a special reunion between him and Campbell. After putting out three albums in four years, the Dirty Knobs have grabbed a hold of their own identity. They’re not just a Heartbreakers side-project anymore.

Campbell is, to put it succinctly, an American treasure. Vagabonds, Virgins & Misfits is a steadfast, deeply rewarding trove of rock ‘n’ roll that features some of the best songs he’s ever written (“Angel of Mercy,” “Dare to Dream”) and puts an incredible emphasis on just how locked in he and his bandmates are. The riffs are colossal, and the rhythms grab you quick and hold you close. Earlier this summer, I hopped on the phone with Campbell to talk about the new Dirty Knobs record, working up the bravery to ask Graham Nash to sing on it, evoking Petty’s spirit while playing with his Heartbreaker brothers and, because I could, that time Roy Orbison, Petty and Jeff Lynne recorded “You Got It” in his Los Angeles garage.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Paste Magazine: I really dig that Vagabonds, Virgins & Misfits opens up with a song about the crowds. You’ve been touring for 50 years, what made right now the perfect time to sit down and pen a track like “The Greatest” and give those thanks to the fans?

Mike Campbell: It was right after the last Dirty Knobs tour. It was such a great tour, and I was so grateful for the turnout and the exuberance from the people. The song was written in about three minutes before the band got to the studio. I just thought I’d like to write something, as a thank you to everyone, and that’s what came out. We played it, I think, once when the guys got there. It’s a very simple song, but it’s just a great way to say: Thank you.

It took 20 years for the first Dirty Knobs album to come out, and now this is the project’s third release in four years. What can you say about not just the groove you’re in as a songwriter, but what such a productive period says about you, Chris Holt, Lance Morrison, Matt Laug and Steve Ferrone?

We’ve been together long enough to have a telepathy. Of course, Steve Ferrone is on the drums—and he was the original Dirty Knob back 15, 20 years ago when we started playing bars here and there. We know each other really well, and we have the same instincts and the same love of playing together. It just gets better all the time. I’m really lucky to have these guys to continue on with my music.

You’re such a focal part of the Heartbreakers’ DNA, so it’s really rewarding for me, as both a fan and a listener, to hear you and the guys trying to find your footing in this venture that’s gone from a side project to a main hustle. It feels like rock ‘n’ roll keeps you honest in that way, that you can’t just take the successes of one group and plug them into another and expect the same results immediately. How impactful has the grind been for you, when it comes to getting a chance to sit down and dedicate time to the Dirty Knobs standing on its own as a band?

It’s greatly rewarding, and thank you for noticing that. I was fortunate enough to be in a really great band for nearly 50 years, and I had a lot to do with that band. I wrote a lot of the songs, and a lot of the sounds come from the way I play. So, when that project ended, unfortunately, I had the Dirty Knobs together in-between Heartbreakers tours for a while, and now I have time to really focus on them. I bring what I do to this band—a lot of the strains of the Heartbreakers’ guitar sounds—and it’s in my DNA, but I also want the Dirty Knobs to have their own identity. And I’ve been working hard to find my own identity as a singer and a lyric writer. I’m starting to get there now where I feel very excited about it. It’s like chapter two of my life, and it’s starting off really well.

I think “Angels of Mercy” is one of my favorite songs you’ve ever written. It just rushes out of the gates immediately and hits you quickly with tough riffs and a great chorus. Tell me, what does a record like Vagabonds, Virgins & Misfits teach you about your songwriting and guitar playing that, somehow, you hadn’t already learned or figured out in the previous 40+ years you’ve spent in the studio and on the road?

The main thing is that I’m writing the songs by myself, as opposed to co-writing with Tom in the past. I’m singing the songs and finding my own character within the song and searching for my own identity. I can’t get the Heartbreakers sound out of my guitar completely—it’s just in there, in my feel—but that’s okay, having strains of it. But I don’t want to just clone that. I want to press on to new frontiers. And, with lyric-writing and the characters I’m really proud of, the songwriting has grown quite a bit since.

By our third album, I think the characters in the songs are stronger, my singing is a lot better and there’s an identity there that’s similar to my old band. I can’t get rid of it all; I wouldn’t want to! It’s got its own thing, you know? It’s definitely a rock ‘n’ roll band. We’re not pretending to be anything else, but we’re also a rock ‘n’ roll band of the truest form—not some new band. I grew up in the ‘60s. I know what rock ‘n’ roll is supposed to sound like, I know how it’s supposed to feel, and I feel like I can bring that to the table. If you want to hear the real thing, that’s what the Dirty Knobs are.

You having grown up in the ‘60s, what do you pick up about rock music in the years after that? Rock music, as a foundation, is as solid as ever, but I think, like any type of music genre, it evolves over time. What have you been absorbing since the Dirty Knobs started over 20 years ago?

Rock ‘n’ roll is a pure type of music, same as blues or country. Their genres that grew out of the South—Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Buddy Holly. That rock ‘n’ roll is rock and roll. There was a swing to it. And then, through the ‘60s, it continued. As time went on, it seemed to be that a lot of rock bands were mostly rock and not rock and roll, which is fine. Nowadays, it’s more of a computerized version of what it’s supposed to be—to my ears. But, like Tom said once: “They’ve taken the roll out of the rock.” And the roll is that secret swing. Chuck Berry invented a lot of it, the way the rhythm floats against the drums and the voice. That’s where I come from, and there’s a feel to it that I can bring that, maybe, a younger audience hasn’t heard yet that way—the way it’s supposed to be to my ears. Rock is just always growing, you know?

It’s funny because, in the ‘60s, when I was learning, that whole renaissance happened with the Beatles and the Beach Boys. It was such an amazing time for a musician to get turned on to music. And, as a kid, I thought, Wow, this is great. This world is wonderful. It’s going to be like this forever! But, as it turned out, that was a little piece of time for 10 years there, and now it’s morphed—it’s growing and continues to grow. When I look back on it, that ‘60s era with all those great bands and songs—and with all the British bands, too, of course—it was a really special time. I’m glad I was there for that, to really experience it firsthand.

A lot of these songs are 15 years old or more, songs that never made it to Tom. What was it like revisiting them more than a decade later, and meeting them where you’re at now, as opposed to who you might’ve been when you wrote them?

It’s interesting, because I’m an addicted writer—a compulsive writer. I write all the time. I have the opposite of writer’s block, I think. Over the years, when I was working with Tom, I would mostly just work on music and hand it to him and, if he liked it, he would write the words. I would just keep writing music all the time, and I have a tape locker here of two-inch tapes of songs that I wrote back then—most of them probably went to Tom, in some shape or form, but they didn’t get used, so they ended up on the shelf. When I was working on this record, my wife actually said, “You should go back to those tapes. You might have overlooked a few things.” I didn’t want to do it, because I want to keep moving forward, but I went back to the tape locker—and there’s still more to go through—but I came up with three or four songs from that era that are really good. “Dare to Dream” was an old song that I had recorded a long time ago as a demo. I had completely forgotten about it, and when it came up, I thought, Wow, this is really strong. This needs to be on the new record.

On External Combustion, you had Ian Hunter and Margo Price play do guest spots. This time, you’ve got Graham Nash and Lucinda Williams on it, and Chris Stapleton returns to play on a track. Having been a bandleader for so long, what are you looking for in collaborators like that? Is it a matter of bringing in someone who you trust and respect to elevate the songs, or do you ever find yourself working with folks who elevate your own musicianship in the process, too? How does having Lucinda sing on a song like “Hell or High Water” force you to go “Okay, shit, I’ve gotta step my game up”?

Lucinda is definitely the cream of the crop. The guest artists on the record were afterthoughts. I had already cut the songs and then, I would sit back and listen to them. “Hell or High Water,” which has Lucinda, I was listening to it and there’s a story—there’s a couple of characters, a guy and a girl, and it occurred to me, Well, it’d be great if there was a female voice that could come in as the character in the song. So I thought about who would be good, and then I thought of Lucinda, who I had met before. I didn’t know her real well, and I begged her to do the verse and she was kind of shy about it. But, she came in and sang that song and made the song twice as good.

Graham Nash was an afterthought. I had [“Dare to Dream”] already finished, and I had done an interview with him and asked him if he would be interested in singing on one of our tracks. I didn’t think he would, but he said sure. And being from the ‘60s, the Hollies are a big influence on me, and I just love Graham’s voice. He sang all the harmonies and came up with a little background part. It was incredible. Then, Chris Stapleton, he happened to be in town—I think he was getting a Grammy Award. He came by the house and I said, “Would you mind maybe singing a verse on this one song?” He said sure, and he went on there. Then, I thought, Well, Benmont could play a great piano on this song—so I called him up, he came over and popped it on.

When you had Graham on your XM show and you asked him to come sing on “Dare to Dream,” was that something that was a matter of in-the-moment bravery, or had you been thinking about that before he was actually on the episode?

The thought crossed my mind, but never in my wildest dreams would I have thought it really happened. I didn’t think I’d have the courage to even ask him. But the interview went so well and he seemed so friendly that I thought, Well, why not? I said, “Would you consider possibly singing on one of my songs?” He goes, “Yeah, I’ll make your song better.” I’m just so lucky. My whole life has been like that. People walk through my life and add richness to my experience, and he’s definitely one of them.

He might be one of the only people who can just outright say, “Yeah, I’ll make your song better,” and no one bats an eye.

He said it in a very humble way—like, “Of course!”

It felt really good hearing Benmont Tench play on “Don’t Wait Up.” That guy has been my favorite rock keyboardist for a long time. When you make music with Steve and Benmont like you have on this record, does it ever feel like Tom is there with you, too, both in the studio and on the stage?

Of course. His spirit is there, and you feel the spirit move through when Ben and I play together. We look at each other and go, “Oh, yeah, remember that?” Tom is always on my shoulder, and I’m still grieving. I’ll always miss him. We were the closest of friends and songwriting partners. You just can’t really negate that, the strength of that bond that we had. He’s always with me, when I’m writing or doing anything. I’ll look at my shoulder and go, “Is this good? What do you think of this? Are you okay with this?” He’s always editing me in my mind, because I love the guy. He’ll always be with me and forever—especially when I play with guys and we’ve played together with him. The spirit comes up.

With the Dirty Knobs, we concentrate on our own music, but I enjoy—and I feel the responsibility to do—a few Heartbreaker songs now and then. Most of them I wrote or co-wrote, the fans like them and I like doing them. I know how they’re supposed to sound, I know how the delivery of the vocal should be, and I know how the guitar should sound. I feel really close to Tom when we do touch those songs. It’s a very religious kind of thing.

When you put a Heartbreakers song in the setlist, do you tend to gravitate towards the same ones every night or do you like to make it a variety at any given show?

There are a couple that work so well within the complexion of our own set that I keep them in. “Running Down a Dream” is one that we usually play at the end of the night. And everybody loves that song, and it’s got a great guitar solo. It’s easy for me to do. It’s not hard to sing. Some of the songs are just too hard for me to sing, so I avoid those. I found a way to do an arrangement on “Refugee” with a waltz rhythm, and the words come across because the words are so timely and they still ring true with what’s going on in the world now. I like doing that song, and the crowd gets into it. They sing along and then, in the middle, we kick into the full-band, rock version. Then, we come back down into the waltz and the audience sings again. I keep that in the show because it’s a real audience participation number, and it’s very emotional.

The other ones, we change them around. I might do “Listen to Her Heart” or I might do—we were just learning a deep cut the other day called “Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough),” which is really good. The Knobs played that really well. “You Wreck Me” will show up every now and then, but I like to change them up—so it’s not a Heartbreakers reunion show, but I can remind people who I am and give them what they want.

There’s a story that I’ve always wanted to ask you about since I first heard it a few years back. But the story of Tom, Jeff Lynne and Roy Orbison writing “You Got It” in your garage. I have got to know about that, because so very few people can say that a figure like Roy made one of his biggest hits at their house.

Well there you go: Mike, the blessed guitar player, had these people show at his house. Tom and Jeff and Roy, to some extent, had already written the song. They came over to record it with me in my studio. You know, Jeff was in charge of that recording—it sounds like his type of production, which is incredible. Roy—that voice. He told me once: “I was born with this voice, and I don’t have an ego about it, but I know that I’m gifted.” The funny thing he said one day when we were over—and I think George [Harrison] was there that day, too, and they were in the other room—Roy was talking about singing, and he goes, “Those guys, they’re not really singers. I call them stylists.” He goes: “I’m a singer.” It’s true, Roy was from another planet. That voice is just from outer space somewhere, it was so incredibly beautiful.

I was just a kid in a candy store during those sessions—getting the sound up, helping record it, playing a little guitar in there and just watching it all unfold in front of me. My heroes, making magic in my house—hard to believe it happened, but it did.

One in a million.

I remember the first time George Harrison came over, too. We were working on “I Won’t Back Down,” and we were going to do all the acoustic guitar strumming. George Harrison’s at my house! I kind of kept it together. Anyway, we were getting the sounds up, and there was a cricket in the garage. The damn cricket ruined it. We couldn’t record because he was so loud. We couldn’t find him, so we had to call the session. We came back the next day and he was gone. There you go, such is life.

The Dirty Knobs’ new album, Vagabonds, Virgins & Misfits, is out now.

Matt Mitchell is Paste’s music editor, reporting from their home in Northeast Ohio.