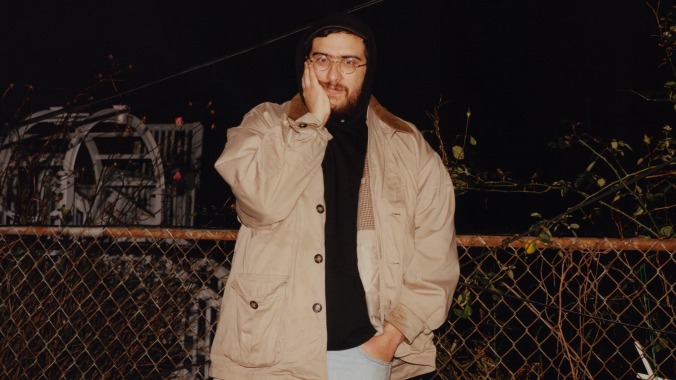

Rui Gabriel: The Best of What’s Next

Photo by Marissa Chafetz

Rui Gabriel’s tenure as one of the best modern musical journeymen has finally paid off. The Venezuelan-born, Indiana-based singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist’s debut solo album, Compassion, has “instant indie-pop classic” written all over it. It’s, as Gabriel calls it, “a coming of age record for somebody who’s coming of age in their thirties”—a good actualization of a momentous creative turn toward easy-going, summery pop music, considering that Gabriel has spent the last decade traipsing through the annals of post-punk with Mac Folger as Lawn. From the bisque-yellow dawn of “Change Your Mind” to the kaleidoscopic road trip of “Summertime Tiger,” Compassion sounds like a musician coming into his own after more than a decade of wearing at least a dozen hats.

Gabriel nods to his dad’s interest in media as being a catalyst for his own music taste—which led to Gabriel’s dad bestowing upon him a magnetic appreciation for Beck’s Odelay and early Green Day albums. “When I was a kid, he started accumulating a lot of CDs,” he says, “and by the time I was nine or 10, I was observing my sister borrowing a lot of those CDs and burning them and making copies. I wanted to do the same, because you gravitate towards what your older sibling is doing.” His dad would let him borrow CDs out of his collection to listen to and copy, or he’d make special mixes for Gabriel. “He’d be like, ‘Oh, you’re into that, so I think you would like this,’” he says. Gabriel is quick to point out how different illegally downloading music in South and Central America is compared to in the United States. “There’s no way that anybody’s going to come at you, arrest you or shut off your internet services,” he says. “I spent ages nine to my early 20s just constantly downloading music.” While Compassion is a hefty dose of pop [X], Gabriel gravitated toward loud, noisy music right away—skipping over any Beatles or classic rock phases in favor of obsessions with Creation Records’ roster, which he explains gave him a “chip over my shoulder” because his reference points were unlike those his peers were exploring. Gabriel’s latest metamorphosis involves him becoming a bit of a Deadhead.

When considering who the artist that he found and adored through his own volition was, Gabriel bashfully admits that he was a Tumblr kid back when the platform made it easy and accessible to put people onto more obscure artists. “There was this band called Dear and the Headlights,” he says. “I was 15 when I downloaded [Drunk Like Bible Times] and I dove into it heavy. It was the first thing that I listened to that I was like, ‘This is my own, nobody else knows about this’—which is pretty gatekeepy, in a way, but nobody that I was hanging out with would give a shit about a band like that, anyways.”

Gabriel quickly acknowledges Deerhunter as a particular tome for him: “Around this time, Deerhunter was getting big,” he says. “This was a few years after Microcastle and leading into Halcyon Digest. I remember when Halcyon Digest came out, because the internet was blowing up about it, and I still take a lot of that influence with me. When I started recording music by myself, I was really bummed out—because I didn’t have a lot of gear. I didn’t have the patience to figure out how gear worked. Halcyon Digest and that Atlas Sound record [Logos] showed me that I can make something really pretty or fucked up with just what I have in the bedroom. I still take that to heart to this day. I have a nice job now and I have friends who are recording engineers and have studios. I have the capacity to do something more hi-fi, but I still gravitate toward just keeping it very simple and not really overthinking much of it.”

While in Nicaragua, Gabriel attended a private high school that used Florida’s state curriculum. There, he was encouraged to take the SAT and ACT and apply to American colleges. “I didn’t really know what I wanted to do,” he admits, “but I knew that I wanted to get out of there.” A self-proclaimed “shitty student for the first two years of high school” and a “very good student for the last two,” Loyola University New Orleans offered Gabriel a scholarship and, with the encouragement of his dad (and the fact that members of the band Caddywhompus were still students there), he moved to Louisiana. “It was really weird, I didn’t know what I wanted to study,” Gabriel continues. “I just picked something. I was like, ‘I’m going to go to class and then I’m going to start a band and whatever happens happens.” As soon as he got to Loyola, he discovered that the college had one of the most sought-after music programs in the United States. “It was intimidating, because I just wasn’t as good as most of these kids who were going to the school for music,” he adds. “And everybody paired up into bands. I didn’t have people to play with, so I just found other people who weren’t in the music program to play music with me.”

New Orleans remains one of the most vibrant music cities in America and, while Gabriel has never felt particularly imbued within it enough to consider it “his scene,” he can’t help but give flowers to his friends who help make the scene as rich as it is, like Video Age and the Convenience. “They’re great people, great musicians,” he explains. “I’d never lived anywhere for more than five years, and I lived in New Orleans for about 11. I’ve been trenchant most of my life.” Gabriel’s dad worked in oil, which meant that his family moved around a lot. “I’ve never had that feeling of feeling tethered to a place before,” he says. “It’s more people than an actual community that I feel close to. But, there is a great community here and everybody I know here makes art, in some capacity or another, and they’re great at it. It’s beautiful, and I love it here. Every time I come back, I get really emotional.”

When Gabriel was in college, the world around him felt like it was just Loyola and Tulane kids in bands playing shows together every week. Once he graduated, it became clear that it wasn’t just college students—it was a whole universe of folks from all walks of life who happened to gravitate toward each other in the French Quarter, which is why the city is rampant with jazz, folk, dream-pop and indie bands. There’s no one color that can encapsulate New Orleans’ musical palette, just as there’s no one color that can encapsulate Rui Gabriel’s music. “When you’re 17 and you’re looking up at 21-year-olds playing music, they look so old and so wise above you,” he adds. “No band here sounds the same, and I always say that, if these bands were in a place like Philadelphia or New York, they probably wouldn’t be playing with each other—let alone sharing members.”

After the disbandment of his college band Yuppie Teeth, Gabriel started Lawn with Mac Folger and Nick Corson. He was going to grad school at the time, and found freedom in embracing a loose playing style and lack of rigidity. “I was so over my head in my other bands,” Gabriel admits. “I wanted things to be so perfect and to sound a certain way and I was really overthinking it. And Lawn was very much like ‘I don’t ever want to play guitar, I’m just going to play bass and I’m just going to yell—because it comes easy.’ It’s going to be rehearsed, but there’s not going to be pedals, there’s not going to be a lot of embellishments.” That’s the mentality Gabriel held until about 2018, when he wanted to prove to himself that he could write and arrange songs in a different way and not just “write a bassline and talk over it for three minutes.” “I felt like I hadn’t written a song at that point,” he continues. “I felt like I had written lines that were just fun to play, but I really wanted to write something that I would want to listen to. It took a long time.” Gabriel began embracing the music he loved when he was young, exploring simplistic textures and tempos and diving into songs that placed heavy emphasis on melody and big harmonies. But at the end of the day, the transition was much more personal for him. “It’s embracing the anxiety of writing music and then being content with the ultimate product,” he says. “When that’s over, you can just let it go.”

Compassion started six years ago, but discerning its origins is one of Gabriel’s self-prescribed weaknesses—aside from “Church of Nashville” being the first demo and “Money” being the last. The album has lived many lives already, and how these 10 songs exist now is as an amalgam of origins, transitions and reappraisals. With Lawn, Gabriel often would write 30 or 40 short songs, present them to Folger, and then let his bandmate decide what worked and what didn’t. He claims that he doesn’t have the best ear when it comes to perceiving that dichotomy in something he’s written. “I kind of just go,” Gabriel says, “and that’s what happened with Compassion in the beginning.” There are four different versions of the album on Gabriel’s computer, finished before, during and after lockdown, and about 20 or 30 songs that may never see the light of day.

That’s how Corson came into the fold on the project. “I was like, ‘I just need somebody to tell me you can work with this, you can make this complete,’ because I just kept recording and recording and recording and having songs that were 50 to 80% finished and I was getting nowehere,” Gabriel furthers. “I sent Nick probably 40 demos and voice memos of just garbage. God bless him, because he sat through that process and he was so patient. He would come over to my house and say, ‘Alright, I listened to these. I think these should be the 12 songs.’” Now that the record is out, Gabriel insists that he’s taking his time writing music now—considering himself “less prolific” but the “most content” he’s ever been. “Now, when I try to go at it, I actually sit down and finish. It might take a couple of days, as opposed to a couple of hours, which is something that I’m very glad that I took from this experience.”

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-