5 Years After the Rolling Stones Saved My Life, I Finally Saw Them Live

In 2019, Some Girls became my soundtrack after a life-altering intersex diagnosis. This past Saturday, I stood 20 feet from the men whose music helped me tell the world about it for the first time.

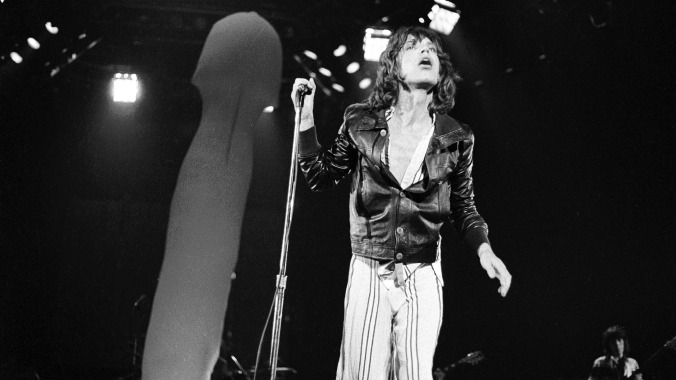

Photo by Fin Costello/Redferns

I don’t remember when the Rolling Stones entered my life. Like everyone else my age, I was born into a present-day the Stones had already existed in for 34 years. They’d already sold millions of albums, had that incomparable run of six records from Their Satanic Majesties Request in 1967 through Goats Head Soup in 1973, and were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame just an hour north of the house I was brought to from the hospital. Even by the time my mom was born in 1970, the Stones had already etched their legacy in stone with Beggar’s Banquet and Let It Bleed back-to-back. My dad was just a year old when “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” hit #1 here in the States. For as long as I’ve been dust, a thought, a wrinkle in time, the Rolling Stones have been here. And I imagine even after Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood, Bill Wyman, Mick Taylor, Brian Jones, Ian Stewart and Charlie Watts are all long gone, they will still be here, forever embedded into the bones, the blood, the atoms, the cells and the breaths of rock ‘n’ roll.

And thus, I’ve known the Rolling Stones because I have no concept of what it means to be a stranger to their work. The commercial crossover of “Start Me Up” and the generational riff of “Satisfaction” came already fortified within the zeitgeist that was handed to me like a birthright, and then I had encounters with more of their catalog in the films and TV shows I later fawned over, like “Monkey Man” in Goodfellas, “Paint It Black” in Full Metal Jacket, “Street Fighting Man” in Fantastic Mr. Fox, “Tops” in Adventureland, “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” in Ozark, “I Am Waiting” in Rushmore, “Out of Time” in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and “Wild Horses” in BoJack Horseman. The New Directions covered “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” in season one of Glee; “Ruby Tuesday” inspired the name of a restaurant my parents used to take me to. The Stones are an epigraph to life as we know it. But, considering all of that, I do know that the first song I ever bought on iTunes was “Beast of Burden,” because I’d heard that metallic guitar riff on Bates Motel and was so transfixed that I searched for its name in the credits and remembered to buy it a week later when I was given a gift card for my 15th birthday.

The band’s anarchist, leftist pedigree soon began to coalesce with my own anti-authoritarian, communist values (“Just as every cop is a criminal / And all the sinners, saints” was a tome). And then, when I was 16 and newly licensed and newly dating, I stole my dad’s copy of Forty Licks CD and discovered “Under My Thumb” and “Tumbling Dice” and “Brown Sugar,” the former of which became my go-to car song. I listened to the Stones at full blast on homecoming night, as I sped 20 MPH over the limit as I raced to O’Charley’s (to have a meal with the girl I didn’t go to the dance with but certainly left in the company of) and got clocked by a cop who let me off. I then listened to the Stones on my way home from a volleyball game where that girl broke up with me. True story: A few days earlier I’d sent her “Tumbling Dice” with the caption “I think this is the greatest song ever made.” “It’s fine,” she replied. Years later, I still thought we were endgame, that our futures were written in the stars and interwoven together.

But my true relationship with the Rolling Stones didn’t really begin until I was in college. At a tiny bookstore in an Ohio town known for a particular Stephen King adaptation being filmed there, I watched my friend Hanif Abdurraqib read a poem about the rock ‘n’ roll mythology of Merry Clayton’s voice crack in “Gimme Shelter,” Mick Jagger saying “Wow” on the final cut of the song and Merry’s miscarriage that came soon after. Predating that, I’d been entranced by the lore of counterculture California and the underbellies of the West Coast, from the Zodiac to Haight-Ashbury to the Manson Family and the New Hollywood renaissance that transformed cinema. That night when Merry came to Elektra Studios on Sunset Boulevard feels like a fable because Los Angeles demands as much.

Hanif would later write of “Gimme Shelter” in his book A Little Devil in America: “I want to know if Mick saw every wretched tooth in the mouth of the world’s most wretched beasts trembling and falling to the ground. There is some awful reckoning to be had in a song like that. Some awful things to be lived with.” The Stones—Mick and Keith, especially—had a knack for making brutalism a lexicon worth becoming a vanguard for. Their music was beautiful and violent, juxtapositions of cherry red flavors and young people dying in alleyways, dreams going up in smoke and genderless love-making for miles and miles. Keith’s guitar riff on “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” is one of the most menacing of its kind, while Mick lasers in the “You got plastic boots, y’all got cocaine eyes” lines like his teeth are jewels hanging from a chandelier. I think, when your life exists only during the days that come between doses of medication, the Rolling Stones are the only rock band with a discography as misanthropic. To have sex with someone while your stomach is covered in red welts and scarring from intramuscular injections, the bruising of “Rocks Off” and “Bitch” sound messianic, satanic and Pavlovian. Plug in, flush out, fire the fucking feed, etc.

A few weeks before my 21st birthday, my roommate drove me to an endocrinologist appointment. I’d grown out of seeing my pediatric specialist, per the Cleveland Clinic’s rules. My new guy, “the adult specialist,” was far more blunt. Because I had been only 15 years old when I was prescribed hormone replacement therapy for the first time—and my parents never thought to educate themselves about it in a meaningful way—I had a lot of questions. My hairline was receding slowly, my teeth growing brittler by the month. After a few years of lathering gel across my stomach and then, after a few years of inoculating my arms, thighs and stomach (and enduring a lot of syringes breaking beneath my skin when the testosterone was too thick for the needle), I’d been put back on a gel (this time on my shoulders) but I could never get the dosage consistent enough to be effective—leading to some seriously acute micro-doses of withdrawal, which I would never wish on anyone.

“I can’t understand how this medicine is helping,” I told my doctor. “You have a sex chromosome disorder,” he responded. “You’re intersex, you need this medicine to survive.” Six years and three doctors later, someone had finally told me the truth I was too scared to embrace on my own. He walked me through what that meant, using the “limited amount of research and findings” about the 46XX male phenotype as ammunition for the lifetime I will spend plumping my body up with synthetic androstane steroids. “This can give your life renewal,” the doctor said, before sending CVS a new prescription for syringes and vials of testosterone. I was to go back to sticking a needle into my muscles immediately. “Put it in your stomach this time,” he added. A pinch and a push, as they say.

My relationship with gender has been a long, complicated one, but nothing can really prepare you for having manhood forced into you. I don’t feel like a woman, though, despite my chromosomes doing their damnedest to put a pussy inside of me. I eventually came out as non-binary because I have felt like a human-sized grey area before my endocrinologist broke the news to me of that fate’s not-so-distant reality. Everyone can refer to you as they/them but, under the weight of hormones you’re forbidden from abandoning, you’ll always be living like a ghost. I’d always thought it would be my choice. More than once I have wanted to quit HRT, and every time my desires have been met with the reiteration that, without it, I am at a higher risk of strokes—a recycled speech about a “general improvement for my wellness,” or something of that accord.

By the time I made it to college, I think my heart had finally just run out of steam. The wall my parents had asked me to put up by hiding my HRT in high school had started to crumble. Suddenly, I was open and upfront about my dosings—unafraid of sticking myself in the company of others, as long as they were cool with it, of course. After that endocrinologist appointment, my roommate began taking testosterone, too, and we would do “injection nights” together. For a brief while, being on HRT felt beautiful and communal. Being a boy and being a girl, and being neither of those things, felt divine somehow. I wasn’t out of the closet as non-binary, nor was I out of the closet as intersex. I was simply existing, writing a lot about HRT and pairing it with my history of chronic illness and autoimmune troubles. My gender dysphoria then felt a lot like the persistent tiredness I’d been touched with years prior, but it’s all just ego death colored differently.

I began working on an untitled poem about my gender dysphoria soon after that endocrinologist appointment, editing and re-shaping it while traveling from Seattle to Los Angeles across 20 days. I had written “In Genesis 3:23, I am the body banished from Eden, sent to dig my boyness out of the ground. In the Myth of Sisyphus I am both the boulder and the pushing” in my notes app on the flight from Cleveland to Tacoma, and I began constructing the couplets around it in fragments as soon as I was experiencing them: buying Sticky Fingers on vinyl in a Crescent City record store, carrying a Coke bottle full of syringes in my backpack, trying on dresses at a Buffalo Exchange in San Francisco, watching a sunrise from an LAX terminal. That summer, I titled it “The Rolling Stones Soundtrack My Gender Dysphoria” and tucked it into the middle of a manuscript I’d been accumulating bits and pieces of throughout college. Suddenly I was writing a bunch of poems about California and about being intersex, more than I could count.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-