Kenya Barris’ #blackAF Is Art Imitating Art Imitating Life

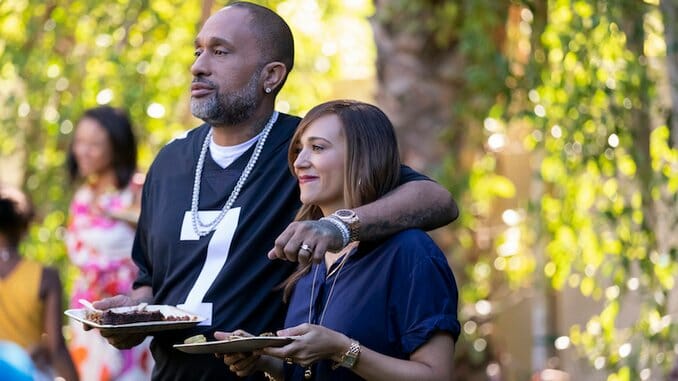

Photo Courtesy of Netflix

If you’re at all familiar with ABC’s black-ish, then watching Netflix’s #blackAF might feel like a surreal experience to you. Not just because it’s created by and starring Kenya Barris, creator and former showrunner of ABC’s black-ish, but because it’s pretty apparent throughout the eight-episode first season that this new series is essentially Barris’ undistilled, unapologetic, unperturbed by network television notes and interference version of black-ish. In fact, it’s hard not to think that this is the show Barris wanted to make all along but couldn’t under the umbrella of his Disney overlords.

Netflix describes the series as “a total reboot of the family sitcom that just so happens to be based on [Barris’] real life approach to parenting.” That’s exactly what black-ish was supposed to be, but this synopsis also comes across like a pointed reboot of that reboot of the family sitcom… which was also inspired by Barris’ real-life approach to parenting. (Tracee Ellis Ross’ character Rainbow was even based on Barris’ then-wife—name, profession, everything.) Only, in #blackAF, instead of Anthony Anderson’s Dre Johnson, it’s Kenya Barris’ Kenya Barris. This is Barris’ first acting gig—it shows, despite him being serviceable as himself—a choice admittedly inspired by Larry David’s work on Curb Your Enthusiasm. Rashida Jones—who appeared on black-ish as Rainbow’s Real Housewives sister, Santamonica—stars as Joya, Barris’ “lawyer” (she’s on an extended break) wife and mother of his six children, who is either a “boss bitch” or an aspiring Real Housewives cast member, depending on the scene. (Jones, easily the onscreen MVP of #blackAF, also executive produces and directs on the series.)

But Barris doesn’t just star as a very meta version of himself in #blackAF: He works predominantly on a set that’s been described as a “nearly exact replica” of his own real-life family home in Encino, CA. And if you’ve ever seen a black-ish scene with Dre at his place of employment, Stevens & Lido, then you’ll get a very distinct sense of deja vu once #blackAF gets to its writers’ room scenes with Barris. Both shows even share actor Nelson Franklin as part of these office debate scenes. Only, instead of Deon Cole in the office as wildcard Charlie, it has Bumper Robinson in the office as wildcard Broadway, with Angela Kinsey filling the role as the one white woman on the team, which Catherine Reitman (who guest stars in an episode of #blackAF) fills on black-ish. #blackAF also has producer/writer Jonathan Groff step out from behind the scenes, as former black-ish showrunner and Barris’ real-life collaborator, to in front of the camera as a writer character on in-show Barris’ staff.

Where #blackAF somewhat diverts from Barris’ original reboot of the family sitcom is its framing device. #blackAF is presented in documentary format, as part of the NYU film school application from Drea (Iman Benson), the second oldest of the Barris’ six children. (Rounding out the rest of the cast of Barris children, from oldest to youngest, are: Genneya Walton as Chloe, Scarlet Spencer as Izzy, Justin Claiborne as Pops, Ravi Cabot-Conyers as Cam, and Richard Gardenhire Jr. as toddler Brooklyn.) Unlike in black-ish, this allows for an in-story explanation for all the voiceover and black history lessons present.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-